by Fathimath Lahfa, Head of Exploration

Listening to the present, exploring the future

October 4, 2022

If someone asks my 10-year-old the age-old question, “What do you want to be when you grow up?”, his answers will vary between a food scientist, a chef or an illustrator or even a video-game developer. When I look back at my 10-year-old self, these were things we did not dream of nor imagined as future possibilities.

Now, here we are, two decades later, me working at UNDP Maldives Accelerator Lab, as ‘Head of Exploration’. Times have changed. I wonder what the future of work may look like for my son’s future. There’s a term again. 'Future of Work'. To some a ‘fancy buzzword’. So, before we move further, we shall define what future of work means for us in development. It is about ensuring everyone in the Maldives will have a decent, productive, and meaningful job – as was cemented in the UNDP Maldives Country Programme Document’s first priority which aims at ‘inclusive, sustainable and thriving livelihoods’.

The challenge is complex but rather urgent as we discussed in a previous blog, A Closing Window of Opportunity. There is a need to think systemically and look at the whole job market issue as a sum of different moving socio-economic parts. Agirre Lehendhakaria Center for Social and Political Studies (ALC) and UNDP Maldives Accelerator Lab have been working together to set up a Social Innovation Platform (SIP) to bring together actors and actions across to co-create and invest in an integrated local development solution that speak to people's needs.

In this blog we share more about the method and the learnings from a first round of reflection which above all entailed a closer look to community aspirations, hopes and challenges.

Why Deep listening?

A deep community listening exercise is a crucial step to gain a deeper understanding of the dynamics around the challenge that put at the center, the need of people as expressed by their direct perspectives. This is done by collecting often personal stories of struggle that all together form a narrative derived from people’s immediate and real concerns.

In a country with 200 inhabited islands spread over 19 atolls, visiting one island and talking to 10 odd people was not going to be enough. This process had to go beyond the traditional surveys and consultation methods. So we set ourselves an ambitious goal to conduct 200+ listening interviews in 20 islands across the country. We tested the field guide and interview tools during several field missions, refined them to better suit the local context. With the help of a local listening team trained by ALC, we conducted 234 listening interviews to understand people's needs, challenges and opportunities around the future of work they wanted.

But first let's take a walk

Before we listened, we walked. We used immersion walks as a rapid ethnography tool to gain an explicit awareness of the surroundings. With guidance and training from ALC team, we employed Spradely’s observation matrix [1], which was articulated around these nine dimensions:

- Space: the physical place

- Actor: the people involved

- Activity: a set of related acts people do

- Object: the physical things that are present

- Act: single actions that people do

- Event: a set of related activities people carry out

- Time: the sequencing that takes place

- Goal: the things people are trying to accomplish

- Feeling: the emotions felt and expressed.

During the first field mission in the three islands of Baa Goidhoo, Fulhadhoo and Fehendhoo, the first thing we did was to observe everyday social interactions. We saw women rushing to wrap up and pack their coconut frond by the sunset, men working on renovating guest houses reopening after the pandemic emergency, young boys playing soccer on the futsal pitch, while elder boys practiced traditional drums on the side of the pitch.

Each exercise offered unique insights of a distinct island identity. We diligently documented the experience with field notes and photos, which were synthesized on a virtual whiteboard after each debrief. This rich layer of observations fueled our listening interviews, pointing to who we should be talking to, what additional questions we need to ask so to have better conversations.

Three levels of narratives

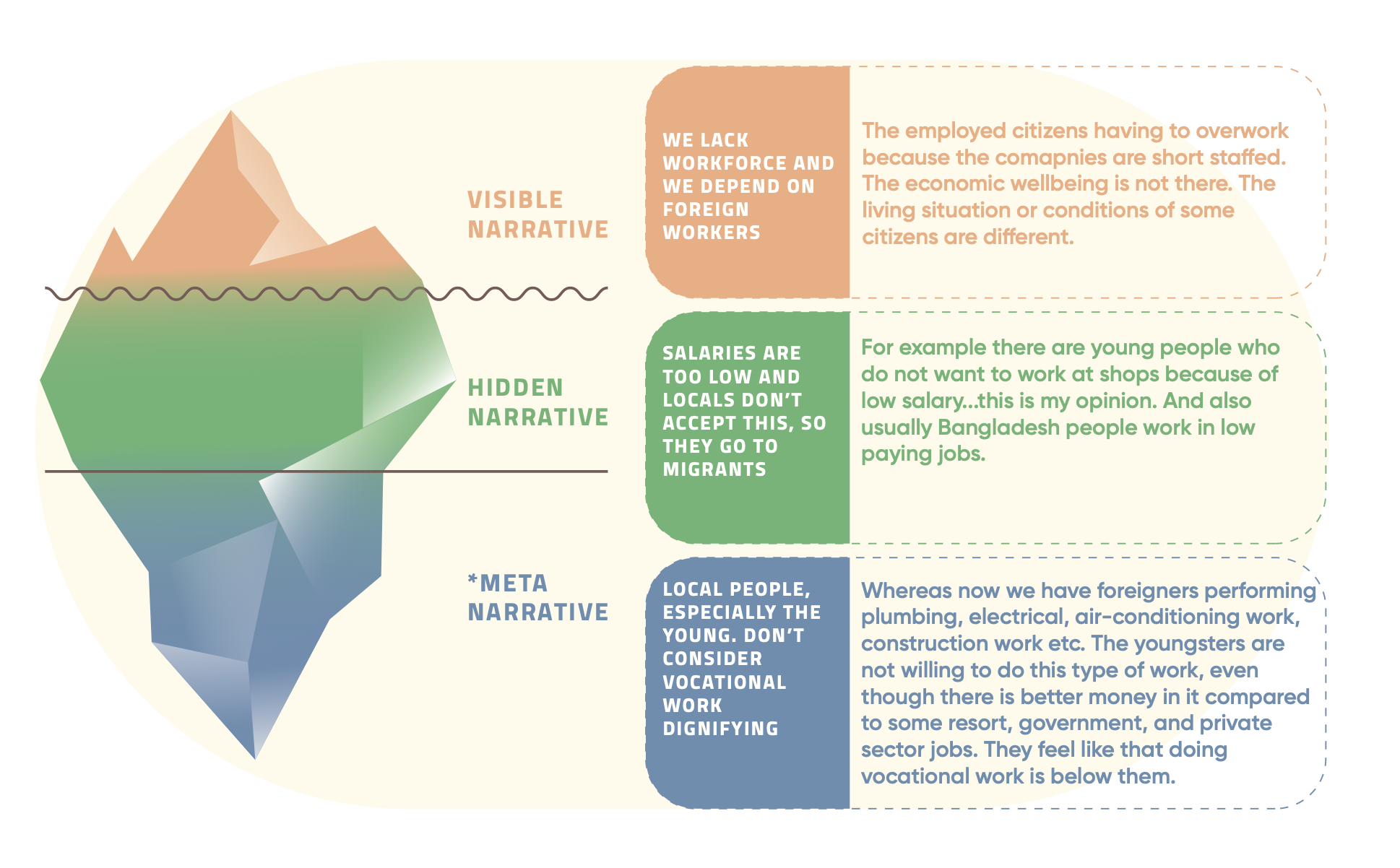

The deep listening exercise provided a wealth of new and qualitative data which were coded into direct quotes. The analysis of hundreds of such quotes were then displayed in patterns that indicated a new set of key challenges as well as emerging opportunities in areas such as blue and digital economy, youth and gender dynamics: it was an entry point to capitalize on new solutions for the jobs being aspired to for their future.

The analysis uncovered:

- An immediate surface matching the emerging public voice;

- A hidden narrative of concerns and

- Deeper beliefs that conditions these narratives

We learned that job opportunities in the islands are very limited so moving to capital Male was for many the only option. We understood that true decentralization of services is the key to meaningfully enact change and that by embracing the opportunities unlocked by technology, remote work could in fact unleash a new job market for all.

Narratives to Personas

To represent the narrative identified during the deep listening process, we created eight personas using the aggregate of common narratives. While the persona is based on fictional characteristics and are not necessarily true to any specific entity, they represent the general attitudes from the perception of the people, exhibited through the literal quotes.

When we unpack some of the challenges around youth and access to work, a number of patterns are often repeated and are valid across the country. For example, one is the belief that Maldives lacks a skilled workforce and thus too often depends on foreign workers. There is also a shared feeling that the education system may not be responding to labor market demands. We recorded many quotes indicating that existing industries like tourism and fishery have evolved, new sectors like creative industry, entrepreneurship and informal work are growing while education and training are yet to catch up to the latest demands of the world of work.

A great share of youth also feels that there is a remarkable lack of opportunities in general for youth to realize their potential. Young people go through education without truly discovering their talents or exploring the full realm of possibilities at hand. Many believe the lack of opportunities is aggravated by the strong presence of power dynamics and political influence in the local culture, suggesting that political affiliation matters the most in accessing real opportunities.

Some of these identified challenges give me a wave of flashbacks from the past because many of these narratives have been operating for decades. Has nothing really changed? However, looking at the identified opportunity areas around remote work, career guidance, changing attitudes towards vocational work gives me hope for the future. The hope that if we can bank on a few of these strategic levers, then we may progress on a Decent Work and Economic Growth for all. A future where one can not only dream to be an electrician, entrepreneur, fish farmer or food scientist, but become one (or any).

[1] James P. Spradley, 1979, Participant Observation.

**Watch out for part 2 of this blog to read about how we collectively made sense of the personas with the communities, and how the personas are leading us to co-create solutions with the communities.

Locations

Locations