Applying Foresight for Exploring Futures of Green Transition in Uzbekistan (HOWs)

Future(s) as a Policy-Making Resource

December 14, 2023

Last year in UNDP Uzbekistan, we started a Futures and Foresight exercise on Green Transition in Uzbekistan guided by the increasing importance of the topic for the country as well as the necessity to apply speculative evidence about the future uncertainty to fill in the blank spaces not filled by quantitative research and evidence. We produced a range of outputs, including a signals database, drivers, narrative scenarios, and several key ideas for policy-making and programming. The exercise was a participatory process involving UNDP programme staff and a wider group of counterparts from various line ministries, government agencies, and non-government organizations. In this blog, we tell about the HOWs of the process, sharing our experience of applying Foresight as a programming and policy-making tool. Also, please check out our blog overview of the results to learn more about WHATs. You can download the Future of Green Transition in Uzbekistan Report and Drivers’ Deck here. |

|---|

“There are winners because there is uncertainty. Without uncertainty, there can be no winners. Instead of seeing uncertainty as a problem, we should start viewing it as the basic source of our future success.”

– Kees van der Heijden

We are used to seeing strategies and policies based on “hard evidence” – statistics, data, facts, etc. However, statistics may hide nuances, data overgeneralize, and facts expire.

Increasing complexity and uncertainty in the systems and ecosystems of decisionmaking make room for “speculative evidence,” contextualized and even personalized interpretations, insights, reactions, etc. Embracing the uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity allows us to generate more valuable insights for strategic planning, identify opportunities for transformation, and anticipate and mitigate risks.

The practice shows that long-term events can only sometimes be predicted. Data and trends may only be accurate with a more profound analysis. The health, climate, humanitarian, and political crises observed worldwide are telling examples.

Thus, it is essential to move beyond just “trends analysis” and, instead, to be prepared for alternative future scenarios. We tried to do this in our participatory Foresight exercise on the Future of Green Transition in Uzbekistan with our national partners. Bringing together relevant government actors, we embarked on a quest to learn about the future and how we can use the future as an additional resource and an edge in designing better policies.

Set up

Our core team included specialists from the Ministry of Economy and Finance, the Center for Economic Research and Reforms, and the Institute for Macroeconomic and Regional Research – the ministry and think tanks with decision-forming roles in this area, and of course, UNDP Uzbekistan staff.

A global team of diverse international foresight experts and practitioners supported the Local/Core team. We also held collective intelligence workshops with a broader group of colleagues from UNDP and participating national partners.

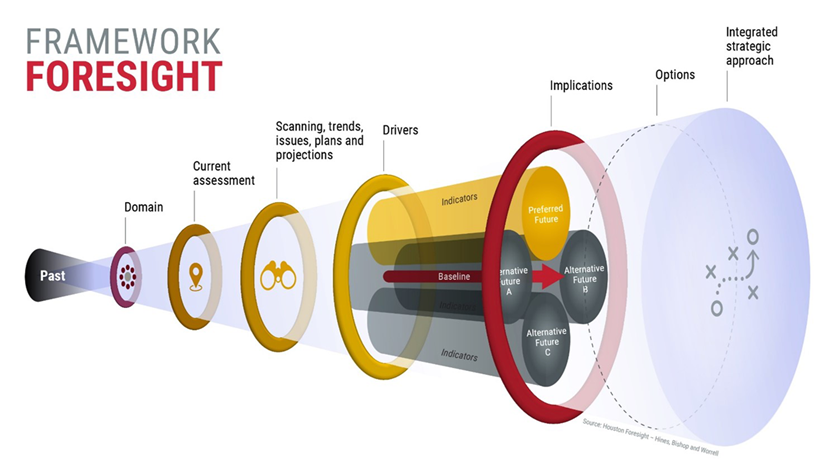

Our approach was based on the Houston Framework Foresight, which features steps like framing, scanning, futuring, and visioning and designing, on which we will elaborate further.

Houston Foresight Framework

Framing

Framing includes domain mapping of the topic. At this initial stage, we tried to identify the key categories and subcategories to explore. As an outcome, we came up with an online map where we explored seven sub-domains and over 60 issue areas categorized under these sub-domains.

The framework served as a point to start the exploration and a reference to come back to align the work. The domain map is also a “living map,” which can be updated later.

Activities: Scoping meeting, Learning webinar Tools applied: Miro (an online collaboration whiteboard platform), convenient to update the map as it evolves |

|---|

A Miro board screenshot of our domain map

Scanning

In the next step we scanned for the “signals of change” across three horizons (short, medium- and longer-term). We researched to identify key trends, issues, plans, and projections that, in turn, were synthesized into critical drivers of change, deriving from (but not limited to) the domain map categories.

Strong (well-evidenced, established trends) and weak (emerging and novel relative to the context) signals were identified through a distributed horizon scanning process using diverse sources (various mediums and languages).

We collected, analyzed, and clustered 454 scan hits to generate mini-narratives, highlight key concepts, and convey relevant emotions and attitudes.

Screenshots from the Newness Signals database

We also had seven interviews with local experts (government, development practitioners, civil society, entrepreneurs, and subject experts) to better understand the local context. Their inputs and opinions allowed us to calibrate our sensemaking process and account for local frameworks.

The results were used in a sensemaking process to identify drivers of change. Applying sensemaking approaches and tools to analyze the data is critical.

In our case, it was the Futures Triangle method. The method is based on analyzing the signals through three lenses: the weight of the past, the push of the present, and the pull of the future.

The Futures Triangle

The sensemaking results of two such sessions helped us to formulate our Drivers of Change. The sensemaking process allowed us to distill the signals into 22 drivers and turn them into the Drivers Card Deck. Each card includes a title, description, and exploratory question.

Activities: Global and local horizon scanning, local interviews, and Driver's workshops. Tools applied: Diigo, a cloud-based library for annotation and Newness (an AI-enabled collaborative scanning platform), to enhance the scanning and sense-making process. |

|---|

Futuring

The Futuring stage involves developing scenarios to create a landscape of plausible futures. Using elements of the morphological analysis, we developed the main points of the scenarios and then used scenario archetypes to tell the story in each case.

Four Scenarios were generated: Baseline, Collapse, New Equilibrium, and Transformation.

Scenario Archetypes

We held an in-person workshop to develop scenarios and implications. Based on the Drivers of Change insights and the interviews, we created “snapshot” scenarios using a modified version of the Scenario Exploration System. The snapshot scenarios were later developed into full-length scenarios.

An element of the Scenario Exploration System

Activities: Scenarios and Implications Workshop Tools applied: Modified version of the Scenario Exploration System, a gaming platform developed for the European Commission Joint Research Centre’s Policy Lab. |

|---|

Visioning + Designing

This stage focuses on impacts/implications (identifying strategic issues and changes suggested by the scenarios), potential strategic options for addressing them, and an integrated strategic approach to the future landscape.

Based on the scenario exercise, we identified impacts (near-term) and implications (mid to long-term). The focus was not only on challenges but also on opportunities.

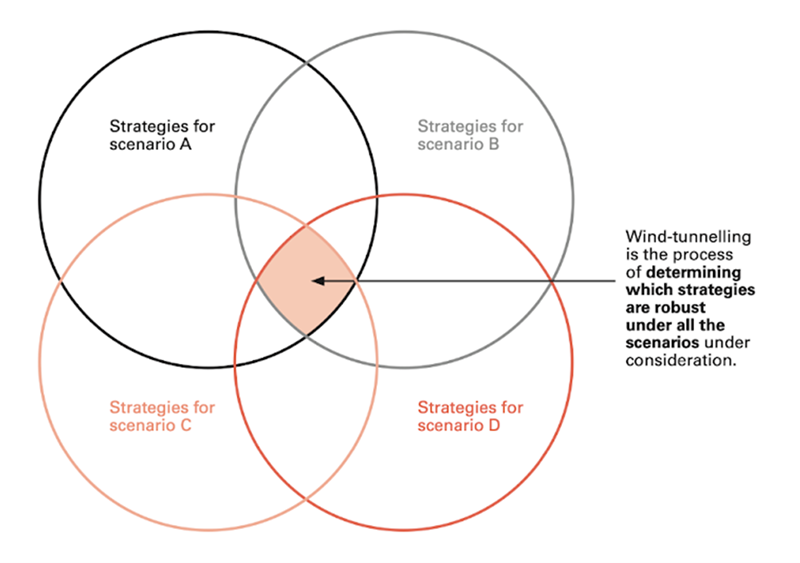

Finally, we generated several “key ideas” that could support implementing the green transition strategy to illustrate the work's practical applications and potential for future scale-up. Here, we applied the wind-tunneling method to determine which strategies are robust under all the scenarios under consideration.

Wind tunneling illustration. Source: Centre for Strategic Futures and Civil Service College, Singapore. Foresight: A Glossary. 2012.

Activities: Scenarios and Implications Workshop Tools applied: Scenario Exploration System, Wind-tunneling |

|---|

What is next?

We have yet to continue our work. It assumes utilizing the process outcomes further and taking advantage of the institutional momentum to grow the capabilities in applying Futures and Foresight tools.

For example, using the results from the process may include:

Creating additional futures (scenarios) with the Drivers,

Carrying out experiments/prototypes based on the impacts and implications

Wind-tunneling strategies and policies with the narrative scenarios.

There is also an opportunity to establish an ongoing “scanning” process that would allow for further exploration of the topic through a foresight lens. Constantly updating signal libraries and generating new drivers and scenarios would enable us to have a future-proofing tool for strategic and tactical policymaking.

It would then lead us to create the institutional capacity and culture for foresight, eventually allowing us to go beyond plausible and projected futures (to get out of the foresight comfort zone).

We generated an initial appetite with this exercise. There are already requests for more strategy formulation exercises from national partners in areas such as national gender strategy and transportation development plans.

We look forward to working on the new application of this approach through a deeper adoption by UNDP and the national partners.

Muzaffar Tilavov is Head of Exploration at UNDP Uzbekistan Accelerator Lab. You can reach him by email: muzaffar.tilavov@undp.org or via Twitter: @mtilavov

Locations

Locations