We have explored solutions in Ukrainian cities that enhance food security and generate co-benefits such as fostering social cohesion and supporting mental health.

Five local initiatives that enhance food security during the war

December 15, 2022

New trend: Urban gardening

According to FAO data, small farmers provide 85 percent of the vegetable supply in Ukraine. Local production helps to mitigate climate change, because shorter supply chains lead to reduced GHG emissions associated with delivery. It is also beneficial for the economy through creating more jobs and fostering cooperation among farms, processing factories, retail networks and the HORECA sector. All of this combined helps local economies to prosper.

In addition to this, and against the backdrop of war, household farming is becoming of new and strategic relevance, resulting in such trends as urban gardening.

The threats posed to food security by military actions have pushed people to plant more vegetable gardens, including in cities. A range of projects for vegetable processing and delivery to the frontline or IDPs has emerged. Apart from the food security, similar solutions contribute to social cohesion and support the mental health of citizens in wartime conditions.

UNDP’s Accelerator Lab has explored solutions that have been implemented in Ukraine and supported five of them. This blog highlights these initiatives.

Urban gardening: Experience of Lviv, Poltava and Uzhgorod

We have seen dozens of food security initiatives and successfully developed some of them through minimal support to the organizers. This is how an inclusive garden in Uzhgorod and a city garden opened by a municipal enterprise in Poltava emerged, and a garden space in Lviv supplied the first batch of vegetables to a local restaurant.

Inclusive garden in Uzhgorod.

- The project, which aimed to create an inclusive vegetable garden in Uzhgorod, was jointly implemented by the charitable organization "Caritas" and the "BUR-Zakarpattia" volunteer centre. The idea of creating a vegetable garden near a shelter for people with disabilities had been under development by the organization for more than a year. The inclusivity of the vegetable garden is ensured by the features of its design: the vegetable beds are elevated above the ground, so people in wheelchairs, who cannot bend down to the ground, now can work in the garden.

- In Poltava, a city garden was created on the territory of the communal company "Decorative Cultures", which in the past grew flowers for sale. Another communal institution, the Institute of the City, took responsibility for organizing the garden. So far, the garden occupies a fifth of the area available for growing, so there is space for expansion. Since its creation, cleaning-up and working parties have been held every Saturday in the garden. In addition, about 15 people visit the garden several times a week. You can see what the Poltava city garden looks like in this video.

- The first public garden in Lviv, Rozsadnyk, was opened in 2018. According to the organizers of the garden – NGO Plato – this year more than 400 IDPs joined in planting and tending vegetables. Vegetables and leafy greens from Rozsadnyk came to the interest of the co-owner of the socially responsible bistro "Inshi" – the famous Ukrainian chef Yevhen Klopotenko. “Inshi” turned beans, chard, beets, and the rest of the vegetables into 20 portions of social Menu #2, which the bistro serves to IDPs free of charge. We discussed this experience with restaurateurs and city authorities and found ways to cooperate in the future. International projects and organizations are usually trusted by representatives of various sectors, and this can help boost such cooperation.

During the project’s implementation we made several observations that that communities interested in promoting urban gardening should keep in mind:

- It makes sense to start planning urban gardening projects in winter, so work on the soil can start as soon as the weather allows. It’s important to plan watering systems or the delivery of water for urban gardens. It is also essential to have an initiative group or an institution that is able to take care of the garden regularly. Eventually, the garden will attract enough citizens to form a stable community, but for the first few years it is necessary to have a proactive organizer to lead the efforts.

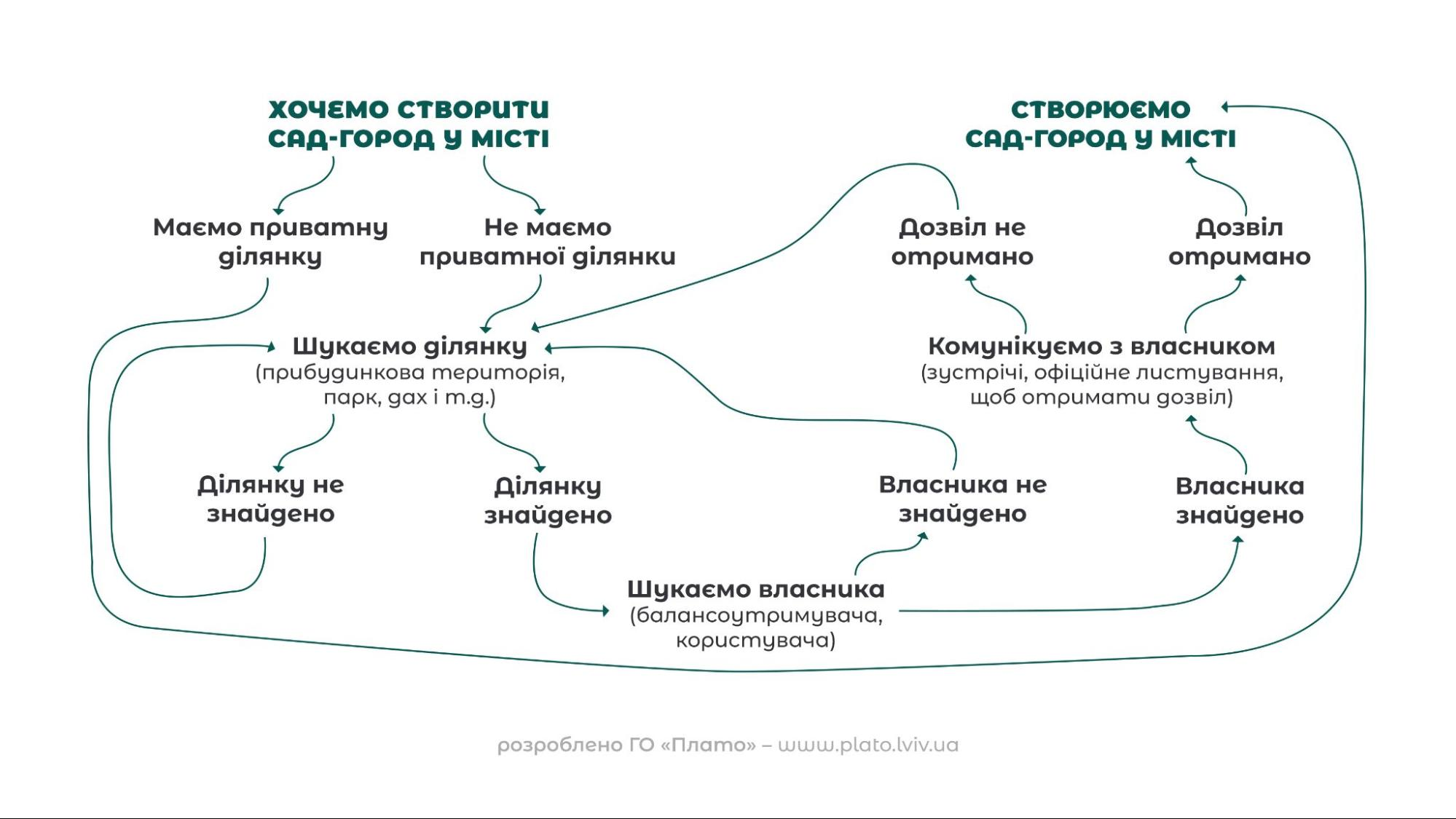

- The planting of urban gardens requires a permit from a landowner: a local authority, or a private or communal entity. We provide more details on the legal aspects of urban gardening in this publication and in this webinar, which was organized jointly by UNDP’s Accelerator Lab, the Victory Gardens project and NGO Plato.

- Various aspects of urban gardening were discussed at other webinars organized jointly with the Victory Gardens project. Recordings of the webinars are available at the Facebook page of the project.

A step-by-step guide for obtaining a land plot for urban gardening.

Building on the existing potential for solution

Despite the war, or perhaps due to the war, Ukrainians are generating dozens of ideas in the food security field.

The “Food unites” ideathon identified a plethora of ideas at the intersection of the social cohesion and food security fields. Several of them were supported by UNDP under the Recovery and Peacebuilding Program. For example, the “Kryvolutska zatirka” project from Donetsk region envisages the production of dried herb sets cooked according to ancient recipes.

Together with this, UNDP’s Accelerator Lab announced an urban garden creation competition and received 37 different ideas. We selected three of them for further support. One of the ideas was successfully implemented without our aid: local activists managed to attract funding on their own and set up an urban garden in Lutsk on a land plot owned by a university. The model of a garden next to an educational facility is easy to replicate in other cities, as most such facilities own adjacent land plots.

Numerous initiatives are implemented in eco-villages, which have been hosting IDPs since the first days of the war. In spring 2022 the new residents of eco-villages started to get acquainted with gardening practices uncommon to them. Thus, with the support of UNDP, better living conditions were created and more people were hosted at the Zelenyi Hai farm in Dnipro Oblast, in the “Zeleni kruchi” permaculture centre, and in smallholder farm of the Bilous family in Khmelnytsky Oblast.

So, in Ukraine there are plenty of initiatives and activists in the field of food security – they need to be contacted, their needs studied, and their initiatives supported. Besides, it is also worth directly connecting the initiatives themselves, stimulating joint planning and cooperation.

Identifying local leaders

We have noticed that the key to the success of gardening initiatives was the engagement of a local leader who could unite the community and coordinate joint efforts.

For example, in the village of Ploska in Rivne region, residents collected around $250 in three hours to purchase a tiller with UNDP co-financing. Ten household farms that cultivate a total of 3.5 hectares of land participated in the joint purchase. The rapid collection of funds became possible because residents of the village knew Taras, a village prefect, to be a trustworthy person. Therefore, it was enough for him to share the proposal in a local chat that had been created to coordinate efforts in the first days of the war. Eight out of 10 co-funders of the tiller have used the machinery at least twice.

Residents of Ploska village, Rivne Oblast, have bought a tiller for land cultivation

In Morshyn, in Lviv Oblast, UNDP’s Accelerator Lab together with NGO “Women’s perspectives” created a vegetable farm in a shelter for IDPs. They grew onions, parsley, dill, sorrel, pumpkins, cabbage, and other vegetables. The yields were used to diversify the food in the shelter. The NGO plans to expand the cultivated area next year because more free land is available. We used the shelter and the garden to analyse what the potential effect of working on the land is for mental health. A preliminary survey of residents of the shelter showed that people who experience difficult emotions more often choose to work in the garden as a kind of psychological rehabilitation. Visitors to "Rozsadnyk" in Lviv also reported a similar effect from working in a garden.

Digital tools to assist agrarians

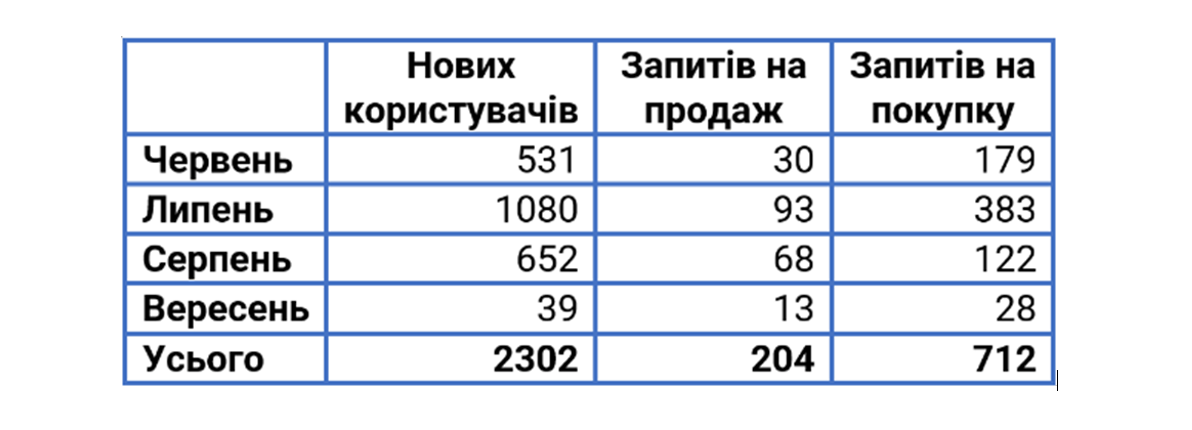

In the Teofipol amalgamated community, in Khmelnytsky Oblast, a community chairman together with a friend launched a Telegram bot aimed at helping local farmers sell their produce. Agrifood producers throughout Ukraine can use the bot. But for it to work to its full potential, at least 10,000 registered users are necessary, so the Accelerator Lab supported its promotion. However, advertising in social networks and targeted advertising turned out to be too expensive: one user costs $5. Therefore, the developers are looking for other ways to promote the bot, including through engaging local opinion leaders.

The statistics of the chat bot usage

Four suggestions of how authorities and international projects can foster food security in Ukraine:

- Simplify the process. Ukrainians are naturally attracted to vegetable gardening. As soon as conditions are in place – the gardens emerge. Local authorities and public facilities can significantly ease the process of creating vegetables gardens by adopting food security programs. A template program was developed by “Victory gardens” initiative.

- Engage community leaders: find people who are respected in their communities, learn from them about community needs, and communicate your proposals through them.

- Keep exploring existing ideas and initiatives, contact their founders, help the initiatives interact.

- Become a hub for cooperation, and a guarantor of credibility. Bring together the initiatives that have a potential for synergy as it has happened with the “Rozsadnyk” urban gardening space and “Inshi” bistro.

More food initiatives analysed by the UNDP Accelerator Lab can be accessed via this link.

Text: Illia Yeremenko

Editing: Tetyana Kononenko

Locations

Locations