By Francis “Kapi” Capistrano and Sheena Kristine Cases

Our Future is Local: Fostering local action in the next 8 years to meet the Global Goals

October 17, 2022

Last July 2022, the new leaders that Filipino voters chose in the recent elections assumed their posts: not only the new President and other national officials, but the new local officials as well.

More than 16,000 local positions were subjected to the electoral will, including 81 governors, 146 city mayors, and 1,488 municipal mayors. Though this marks a changing of the guard, many have remained in power. For example, 40 of the 81 victorious Governors were re-electionists. If the endorsed successors—including parents, spouses, children, or other relatives and allies—are included, an overwhelming 78% of gubernatorial seats were kept by the incumbent.

These “new” local leaders faced a “happy” challenge when they assumed office. This year, the landmark Supreme Court decision on the Mandanas-Garcia case took effect, effectively giving local government units (LGUs) an almost PHP1-trillion (nearly about USD 20 billion2) increase in their share of national taxes. Happy, because the LGUs earned a windfall that they could use to build more infrastructure, deliver more services, and address development challenges.

A challenge, nonetheless, because the optimal and proper use of these funds must be ensured.

That is, if local funds are being spent in the first place

A significant part of the challenge is in the ability of LGUs to utilize these resources in the first place. Based on the latest data from the Bureau of Local Government Finance (BLGF), LGUs incurred a fund balance of PHP 597 billion (about USD 11.9 billion) as of the end of 2021: PHP 167 billion (about USD 3.3 billion) for provinces, PHP 247 billion for cities (about USD 4.9 billion), and PHP 183 billion (about USD 3.6 billion) for municipalities. Though this amount may include some funds reserved for outstanding payables, the amount nevertheless represents the magnitude of resources that these LGUs have not been able to mobilize for urgent and priority initiatives.

As local government resources grow significantly due to the Mandanas-Garcia case, the gap between revenues and expenditures widens further. (Data source: Bureau of Local Government Finance)

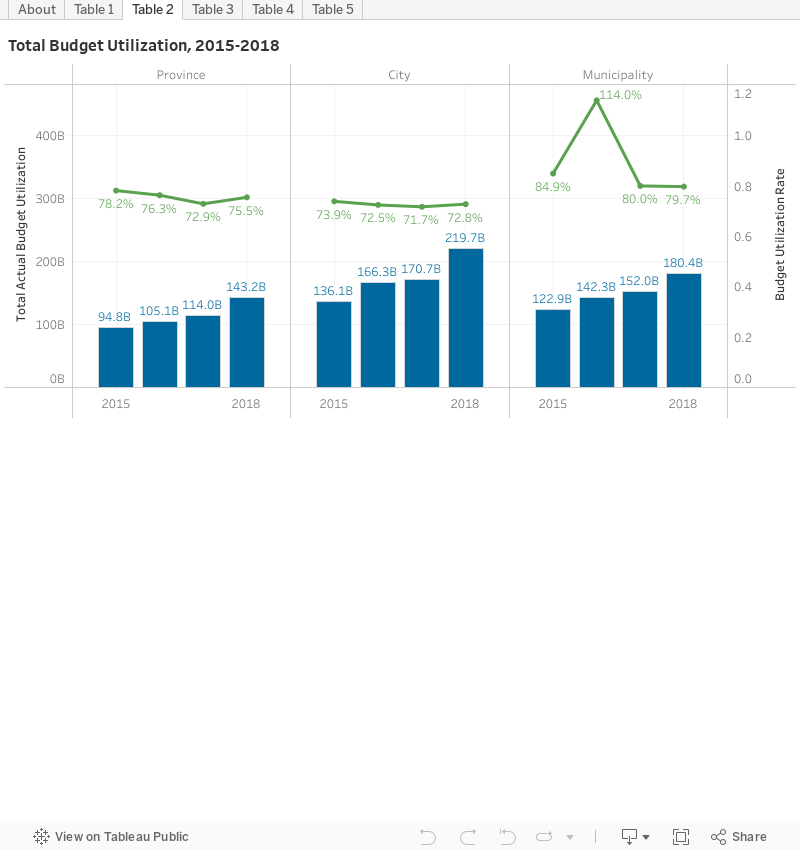

Here’s a more glaring figure which illustrates this capacity gap: LGUs are not able to spend about one-fourth of their budgets. Based on a World Bank study that uses a novel approach4 to derive budget execution data of LGUs from audit reports in 2015 to 2018, provinces, cities, and municipalities have average budget utilization rates (BUR) not exceeding 80%. The study predicted that budget execution will worsen as Mandanas-Garcia takes effect.

Data source: Commission on Audit local government audit reports as compiled by the World Bank

In other words, about 20% to 30% of the LGUs’ budgets is not spent.

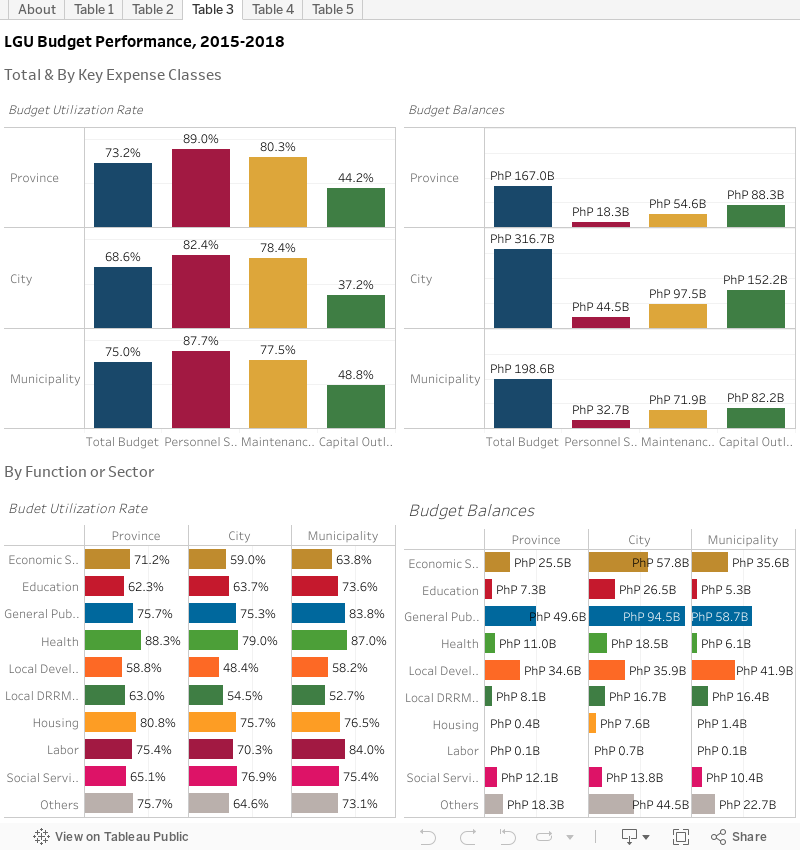

Where do LGUs tend to underspend? Crunching the data that our colleagues at the World Bank provided us, we found that spending on capital outlays—local roads, classrooms, computers, and other infrastructure and equipment—reached less than half of what was budgeted. By function, Local Development Funds (LDF) utilization did not exceed 60% on average. The graph below shows how spending on necessary functions like economic services, education, disaster management, and social services fell significantly below what was planned.

Data source: Commission on Audit local government audit reports as compiled by the World Bank

A new way of public financial management needed

Public funds have stereotypically been likened to water in a leaky bucket, with the holes symbolizing graft and wastefulness. But in this case, local public funds could be akin to ketchup stuck in a bottle or toothpaste refusing to be squeezed out. While corruption and waste sure need to be curbed, the slow utilization of public funds is an inefficiency that leads to forgone opportunities to address long persistent concerns that the country has been facing.

With the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG), UNDP Philippines commissioned four studies that look at the policy implications of the Mandanas-Garcia ruling. The studies attempted to look beneath the persistent challenges of local fiscal management and governance to unpack how LGUs can strengthen their ability to use public resources, address conflict and crises, and harness citizens’ voices to meet their local development goals.

DILG and UNDP plans to release the research compilation before this year ends. Ahead of this, we’d like to share some of the key insights5.

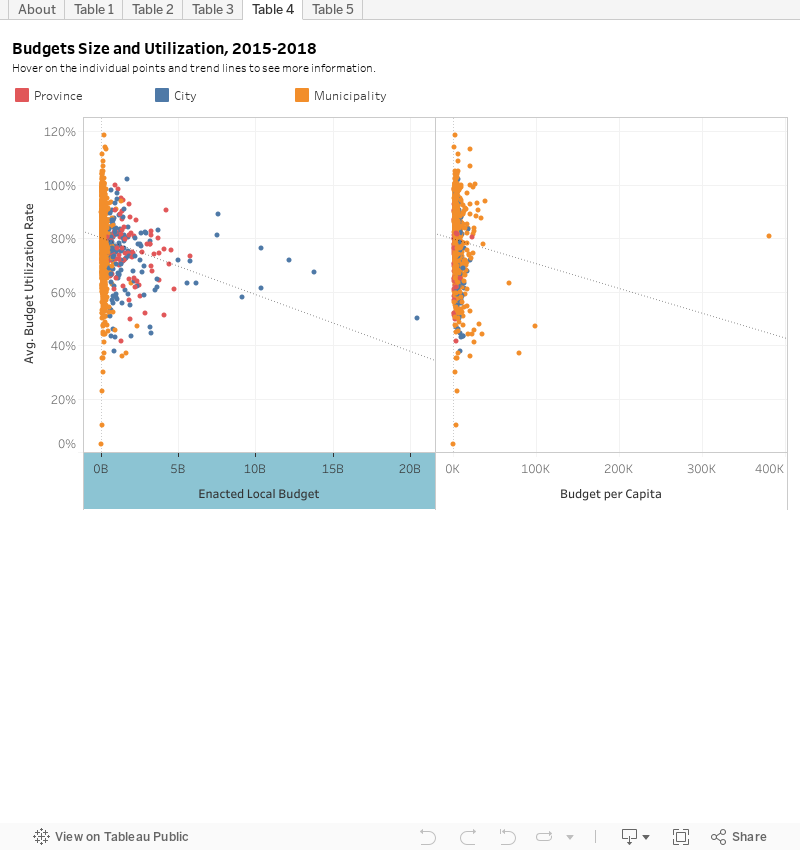

The disparity in the technical capacity of LGUs is quite stark. LGUs which have larger budgets tend to have lower budget utilization rates, with cities and provinces raking in huge budget balances: as high as PHP 11 billion for one city alone. This begs the question: why do LGUs which supposedly have more resources and stronger capacities tend to perform worse at least in terms of budget utilization, while those who need more (i.e., poorer LGUs) are left to be dependent on national transfers? This seems to be a systemic issue of equity across LGUs that may require a rethinking of how fiscal resources and governance functions are distributed.

The glaring gaps in the “technical capacity” across LGUs also need to be unbundled: are these in the lack of goods or services to buy (e.g., not enough capable contractors in an LGU); in the capacity of LGUs to manage funds (e.g., the notoriously tedious procurement process); or the implementation readiness of plans being approved in the first place? All LGUs demonstrate all these capacity gaps in one form or another. Thus, rather than debate which one problem matters the most, these need to be attacked systemically and in a manner that attunes the interventions to LGUs’ specific needs, such as in crisis preparedness (fun fact: those LGUs who score high on disaster preparedness metrics also tend to have better budget utilization).

Data source: Commission on Audit local government audit reports as compiled by the World Bank

That new way should make local voices matter

The “new way” of managing local finances should make sure that local voices count. If we want LGUs to be more anticipatory, adaptive, and agile (“AAA”), then it should have the capability to harness all possible viewpoints, suggestions, and contributions from citizens to solve local development problems.

Participatory governance is, of course, not new. On that note, credit must be given to the DILG for pursuing reforms across multiple administrations to strengthen and institutionalize the participation of citizens through civil society organizations (CSOs) in local government affairs. This is a commitment of the Philippines to the Open Government Partnership that entails, among others, instituting mechanisms for citizen participation and adopting “civic tech.”

What other tools, methods, and mechanisms can enhance these efforts and promote “AAA” governance through citizen participation? Earlier this year prior to the political transition in July, UNDP partnered with the Philippine Partnership for the Development of Human Resources in Rural Areas to promote multi-stakeholder engagement in COVID-19 recovery and devolution transition planning. Called “AAA Recovery Project,” this engagement builds on our collaboration on local convergence with the Zero Extreme Poverty (ZEP) Philippines 2030 coalition.

In each of the 15 LGUs covered by the initiative, we tapped local CSO leaders to convene multi-stakeholder networks in their respective localities and seek the buy-in of the LGU leaders to the participatory exercises. These networks identified the priority development issues in their localities aided by data on poverty and SDGs provided by UNDP. Using anticipatory methods introduced by UNDP, the networks envisioned scenarios of how these priority issues could play out depending on critical factors. The networks then co-created their proposed recovery plans or agendas that are reflected in this compendium.

How have these participatory plans been fed into the LGU’s own plans and programs? Although it is quite early to tell, discussions we have so far done indicate that the LGU officials appreciate the exercise and that they intend to use the contents of the participatory plans for ongoing local development planning processes. The local convenors themselves—many of whom sit in local development councils—are keen to continue the engagement with LGUs while drawing support and collaboration from the multi-stakeholder networks.

Ultimately, it’s about ending poverty

We released this blog in the midst of two crucial milestones. First, this October marks the 31st Local Government Month to commemorate the enactment of the Local Government Code of 1991. October 17, meanwhile, is the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty.

Decentralization is considered a powerful tool for reducing poverty and promoting sustainable development. LGUs, after all, are closer to their constituents compared to the central government, and thus, are in a better position to provide public goods more responsively and efficiently (for a classic framework, see William Oates’ decentralization theorem). The Mandanas-Garcia ruling corrects the computation of LGUs’ allocations from national taxes and, in effect, makes more resources available for their priority programs and projects. That is indeed a landmark ruling, but unfortunately just one of the important steps.

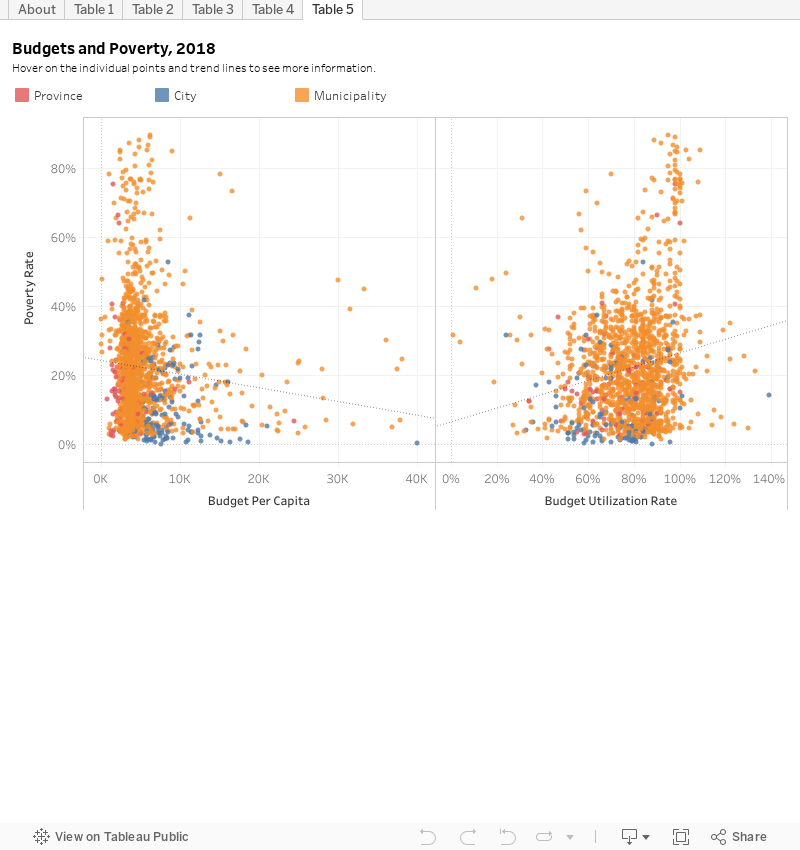

In 2018, LGUs with higher poverty tended to have lower budgets (total and per capita) but higher budget utilization. (Data sources: World Bank (2021) using LGU audited accounts (COA); PSA (2022) small area estimates of poverty for 2018.)

Much work needs to be done to correct the significant disparities which remain among LGUs about their access to resources and capability to deliver public goods and services, towards meeting local SDGs. Part of the task, we believe, is in fixing the disparities in how open these LGUs are: to innovations; to greater political accountability; and to increased collaboration with civil society, private sector, and the citizenry. Only then can collaboration and collective action be enabled to solve multiple challenges, even those that may not have been imagined yet.

The future of development is local. The future of local is open. [E]

About the Authors: Francis "Kapi" Capistrano is the Officer-in-Charge of UNDP Philippines' Impact and Advisory Team. He is also the Head of Experimentation of the UNDP Accelerator Labs Philippines. Sheena Kristine Cases is the Data Analyst of Pintig Lab, UNDP Philippines' multi-stakeholder network of data practitioners and experts tasked with providing the government with data-driven systems and policy insights to help inform the national COVID-19 response and recovery strategy.

Locations

Locations