A reform of the system for happier childhoods and smoother lives

August 25, 2022

Balša Marljukić

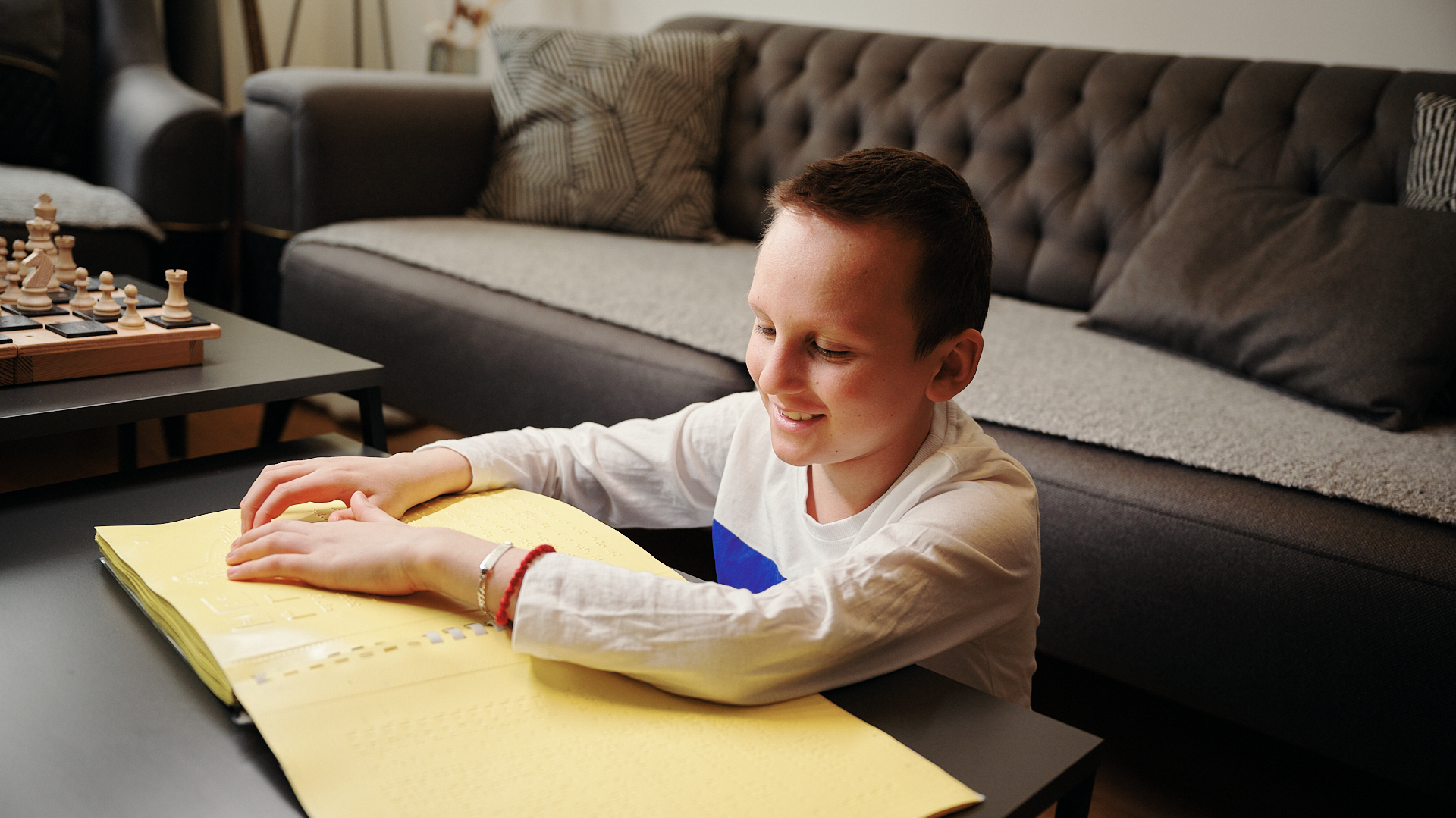

Ten-year-old Balša Marljukić learns Braille, rides a scooter and plays chess with a warm, broad smile.

"When I grow up, I would like to be a chess teacher and teach other children,” he says. “I wouldn't mind teaching those who can't see, like me, to play chess.”

Due to a severe illness, Balša completely lost his vision at the age of five.

Since then, hospitals and paperwork have become an inevitable part of his life. Just as he strategizes and makes moves on the chessboard, he and his mother Dragana Joksović do the same in real life to provide Balša all his rights.

Balša Marljukić and his mother Dragana Joksović

According to the last census, as many as 11 percent of Montenegrin citizens have difficulties while performing daily activities due to a long-term illness, disability or old age. While trying to live, study and work, they face numerous barriers: complicated procedures, lack of information and society's prejudices. To exercise most of their rights, they have to visit several different disability assessment commissions and face lengthy processes.

"No one has ever instructed us or helped us: 'Do it this way, it’s easier for you, bring that paper, you can do that here.' I had to go from one counter to another and plead with someone to explain things to me," Dragana says.

In Montenegro, there are 30 different assessment commissions that offer findings and opinions on the rights of persons with disabilities. Decision-making criteria are not uniform and a person often has to return repeatedly.

"I had to go and show up before the commissions several times for the same thing, and no one would pay attention to us,” Dragana says. “Eventually, someone took a closer look at the documentation and finally approved our personal disability allowance.”

Slađana Dakić at her workplace

Slađana Dakić faces similar frustrations. She loves her job as an assistant costume designer, but to improve her skills and knowledge, she needs a hearing aid. Although she applied for the device twice, she has been waiting almost two years.

"I had to file the application twice, because the first time I wasn't well informed,” Slađana shares. “It’s stressful for me - I’m afraid I won’t get it soon enough. Work is difficult without it, although I have the support and understanding of my colleagues."

"I waited for the disability assessment commission to see me for more than a year. The process is long, stressful and exhausting.”

Finally going to meet the commission was just as unpleasant for her; the crowded corridor and noise made it difficult to hear when her name was called. And after waiting so long for the appointment, she was disappointed in their lack of attention.

"When I entered the room, two doctors only told me to hand over the documentation and didn't ask any questions. I wish I had experienced a slightly different approach, that they had explained to me what my assessment of 60% disability actually meant,” she admitted. “I would have felt encouraged if they had said this percentage was not an obstacle to my independent life and work.”

Ismar Ramović at hir workplace

Ismar Ramović, who has an intellectual disability, waited for a job for almost three years after he finished school. To get the opportunity to work, he went through long and complex procedures. In addition to the medical one, Ismar had to show up before two other disability assessment commissions.

"I wish I could finish everything in one place. I don't like crowds and waiting,” he says. "I am anxious when I go to meet those commissions.”

People with disabilities often aren’t informed about their rights and depend on these assessments for decisions affecting their lives. For example, the commission's assessment sent Balša to a resource center instead of a regular primary school.

"The moment she met Balša, the teacher said that he didn’t belong there, that their center’s curriculum was not adapted to his abilities,” Dragana admits. “She said Balša should go back to regular, inclusion-based schooling. I was not even aware that there was such option until that moment."

Balša Marljukić reading Braille

Similarly, Slađana didn’t know that she had the right to a disability assessment and professional rehabilitation.

Life without barriers would be easier for all of them if information was easily provided and procedures completed in one place. But now, UNDP, the Government of Montenegro and civil society organizations are working together to reform the disability assessment system - a project supported by the European Union.

Through that reform, disability levels and needs of all people with disabilities will be assessed in one place. This will simplify procedures significantly and make the system more accessible. Assessments will be made based not just on the medical model applied thus far, but also on a human rights one. This includes the barriers they face and the support required to overcome them and lead an independent life.

“I wish there was a team that would help us and understand our situation and what barriers we face.” - Slađana Dakić

Slađana Dakić with her costume designs

Systemic barriers, however, are not the only ones she has had to face. Societal prejudices pushed her to hide her disability so she could get a job.

"They thought that my hearing impairment would prevent me from doing my job properly. They didn't understand that, like everyone else, I needed to work, engage myself, and advance in what I do", she says. Now, at least, her colleagues are understanding.

Ismar Ramović making souvenirs

Ismar is thankful the environment at the souvenir-making company where he works is supportive. “It's nice at work, because I feel at home,” he says. He likes working with machines, making boxes and magnets.

Persons with intellectual disabilities in Montenegro are often not understood, supported or accepted by the society, but that is not the case with Ismar. "I hang out with colleagues at work, and after we go for coffee. Sometimes we play football or basketball," he adds.

Employment is a precondition for independent life and inclusion, and the state offers benefits to companies if they employ people with disabilities, by subsidizing salaries and funds for workplace adaptation.

Ismar’s employer Nebojša Milikić says he has made a lot of progress. "He contributes to himself and our company with his work and results.”

Meanwhile, Balša is also making progress . While he waits for the system to be improved, he looks forward to going back to school, seeing his friends and perfecting his chess skills - because it is not easy to become a grandmaster!

Balša Marljukić - future chess champion!

(The story was originally published by UNDP EURASIA)

Locations

Locations