For decades, isolating people with disabilities, having deprived them of their social rights, was considered quite normal for the Republic of Moldova, a former Soviet Union country. About 20-30 years ago, people with disabilities "were invisible" in the public space, some even thinking it was a shame to admit publicly having a member of the family with disabilities.

In years of struggle for the claiming of the rights of people with disabilities, we have understood that participation in elections and political involvement is the way to promote their rights. In Moldova, there are more than 180 thousand people with disabilities or 5.1% of the population (according to latest 2017 official data), out of each 170 thousand are voters. In Moldova, elections are conducted every 2 years: general, local and presidential. Sometimes even more often, if early elections are to take place.

We started our journey back in 2012, in partnership with the electoral body – the Central Electoral Commission, by supporting to create conditions for people with disabilities to vote, in accessible spaces and to raise awareness on this matter. In 2016, we managed to equip all polling stations with template envelopes for ballot papers that allowed for secret and accessible voting of visually impaired people. Before, persons with visual impairments could vote only if they were assisted by someone who was telling them what is written on the ballot paper and guiding them to put the stamp.

Also, for polling stations serving persons with hearing impairments, sign language was provided, with UNDP support. Since 2014, all election day announcements, and since 2016, voter education videos are accompanied by sign language translation.

In 2018, a pre-election year in Moldova, UNDP supported a civic campaign to inform hundreds of people with hearing, intellectual, and psycho-social disabilities about their electoral rights. For information to be more accessible and attractive, we have developed tailor-made information guides: audio and Braille versions, accessible to people with visual impairments, as well as an easy-to-read, easy-to-understand guide for persons with psychosocial and intellectual disabilities, a absolute first for the Republic of Moldova, produced in Romanian, Russian and English.

However, the challenge of accessible public spaces persists, since the absolute majority of public buildings hosting polling stations are inaccessible: no access ramp, toilet, narrow entrance door and/or corridors etc. In these conditions, people with disabilities have to compromise by requesting the mobile ballot paper at home. While this option is recommended for certain physical conditions, it is definitely not appropriate for all cases. Some of the voters note they feel ashamed to vote at home and even report attempts to influence their choice.

"After the accident I had, for one and a half year I was ashamed to go out in public. When I was going to the hospital, I was always waiting everybody to leave so that to go out of the car and go into the hospital or other institution, no matter which one. I felt myself very ashamed. During my recovery period, two elections were hold.

I voted at home and I didn't feel comfortable at all with this situation. Then, I decided to go myself to the polling station every time when elections were hold, so I felt myself fulfilled and equal with any other person," told us Vasile Savca, from Causeni district.

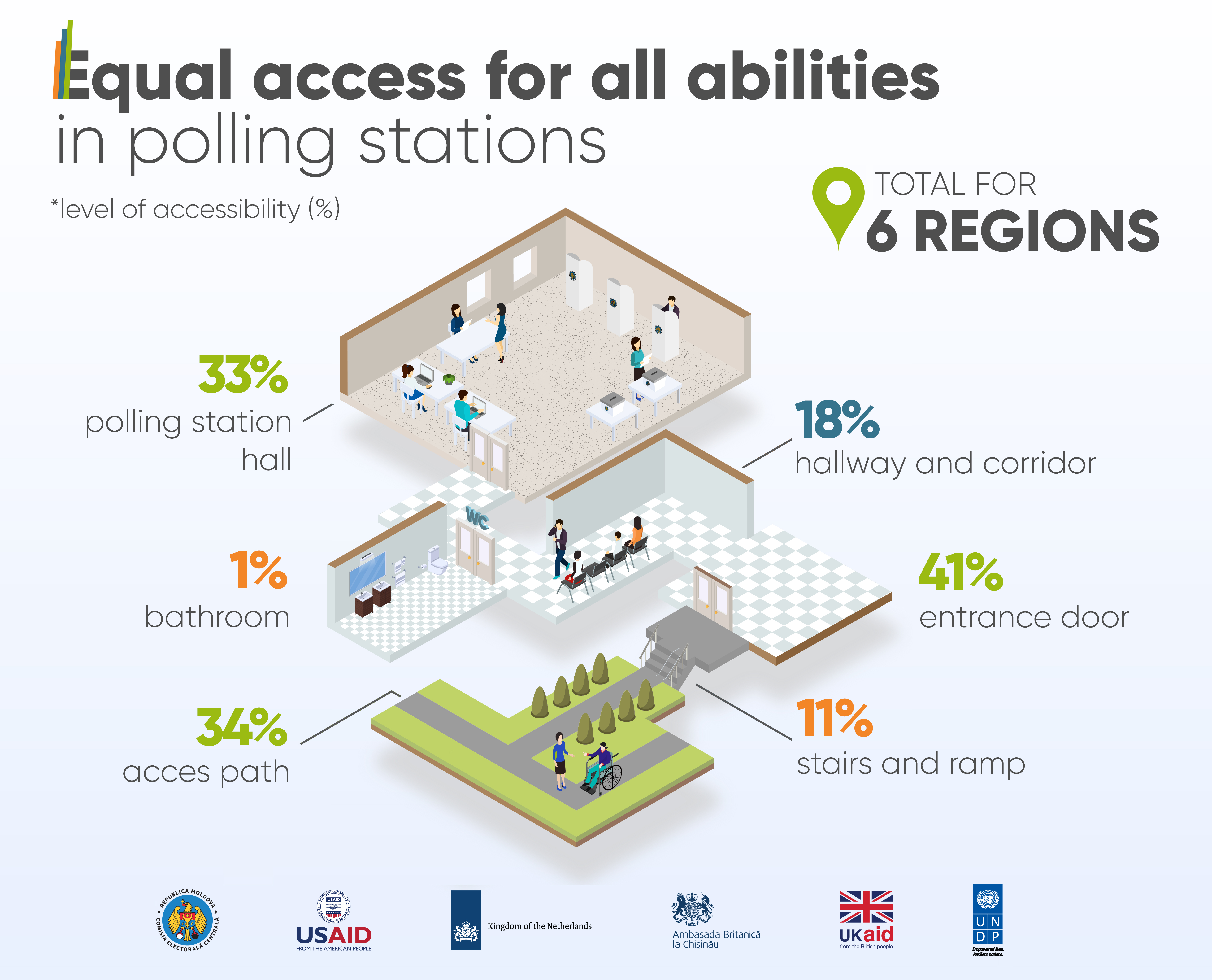

Vasile was one of our 16 accessibility monitors we teamed up with last year to advocate for accessibility of public spaces. We had in total 36 volunteers who had to fill in an accessibility checklist by visiting 612 polling stations from the total number of 1969.

We at UNDP Moldova made use several times of the user safari, as there is no one better to spot the weaknesses when it comes to accessibility than with people who experience those challenges first-hand. That is how we improved the accessibility of the UN House in Moldova and created a model community police station in Chisinau.

Even we knew ourselves that the results would reveal a bumpy road, we were stroke by the results: only 1% of the assessed buildings are fully accessible.

Before that assessment, the Central Electoral Commission did not have any data about the polling stations' accessibility across the country. If we consider that 60% of public buildings hosting elections are educational institutions, the conclusions are even more striking.

Moldova has in place all international commitments and national legal provisions. The country has ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in July 2010. The Convention lays down the obligation of the State Party to ensure accessibility to persons with disabilities. Law no. 60 on social inclusion of persons with disabilities contains provisions on physical accessibility. Construction regulatory guidance of June 1, 2014 provides for requirements to ensure physical accessibility.

In these circumstances, why does still Moldova struggle with the inaccessibility of public buildings? Human rights experts note that people don’t realise how serious is the issue of accessibility, thinking that this does not concern or affect them directly. Mayors and local administration sometimes don’t prioritise it and place it in the end of their “to do” list, which tops with health, education, economic growth. Another concern is that local architects and engineers do not yet master the criteria for an accessible venue and options to make it possible. Also, there is need for much more social pressure so that central authorities ensure measures of accessibility.

A myth we are striving to debunk is that accessibility would require a lot of money from local budgets. In our discussions with the local authorities, we gave them as an example a simple yellow duct tape that costs only $3, which indeed helps the visually impaired move safely, but misses in almost all public buildings. An example you can see at one school in the south of Moldova.

In conclusion:

- Public spaces accessibility does not concern only the people with disabilities. In reality, more people are affected, namely the elderly, children, parents with infants carrying them in strollers, pregnant women, bicyclists and people with temporary disabilities;

- Accessibility may be improved at minimum expense.

Our recommendations are to:

- Ensure strict compliance with accessibility requirements and impose conditio sine qua non in the process of commissioning the new facilities;

- Include modules and universal design on accessibility in the curricula of relevant specialties;

- Set up a “warning system” in the area of accessibility, where citizens could flag up all irregularities, enabling the authorities to interfere and address them timely;

- Train the electoral officials and local government representatives on accessibility issues;

- Use crowdsourcing and crowdfunding resources for accessibility projects.

UNDP will continue to work closely with electoral management body and local governments to improve accessibility of public buildings. Also, we will advocate for a budgeting process that is sensitive to the needs of people with disabilities.

Locations

Locations