By Roland Nassour, Urban Recovery Officer, UNDP Lebanon | Elias Mouawad, Head of Exploration, UNDP Accelerator Lab Lebanon

Beyond the emergency response: A neighborhood approach to recovery in the area affected by the Beirut blast

February 18, 2022

Aerial view of the Karantina neighborhood - By Sara Yassine

Walking through the streets of the area affected by the Beirut blast, a curious stranger might struggle to find traces of the explosion: frontages shine with lively colors, glass windows look crystal clear, and doors fixed and safe. Hundreds of posters, hung on the street walls, inform the passerby of the various initiatives offering social support to vulnerable communities. So far, the neighborhoods are recovering. Or that’s what you might think.

The recovery efforts are challenged by the nationwide economic crisis deepening by the day. Behind the colorful facades are families losing income and businesses closing, despite the integrated support programs. But there is more to the story. The blast response, necessary as it has been, has itself created unintended harms. The Tensions Monitoring System of the UNDP reported stoking intra-communal tensions in Beirut, as people felt that their priorities, knowledge, and dignity were neglected, because of the unaccountable assessments, uncoordinated aid, and the exclusion of communities from decision making. These insights testify to the limitations of the blast response in dealing with the context-specific vulnerabilities in an urban setting marked by weak governance and instability.

A more sensitive approach is thus needed, one that establishes an organizational infrastructure for improvement, by maximizing collaborations, building collective capacities, and ensuring local ownership. In this article, we explore our ongoing effort towards a holistic recovery on the neighborhood level. It is the first of a series that sheds light on the neighborhood recovery framework currently implemented in Karantina, one of the most vulnerable neighborhoods in Beirut.

Why the Neighborhood Approach?

Despite the overarching problems facing Beirut today, each neighborhood suffers from different socio-economic vulnerabilities intertwined with different spatial configurations of the built environment. These differences manifest within the area affected by the blast, as evidenced in the post-blast socio-economic assessment conducted by UNDP. A neighborhood approach to recovery is crucial, as it tackles otherwise overlooked issues, by looking more surgically into specific geographic areas where people have common needs and priorities. Working at the neighborhood scale allows the efficient engagement of various stakeholders and the inclusion of diverse community groups in the process, thereby reducing inequalities and narrowing the accountability gap. Additionally, the neighborhood approach entails the implementation of multi-layered, people-centered solutions across sectors. The learning accumulated from this approach can form the foundation of a bottom-up city-wide urban recovery framework.

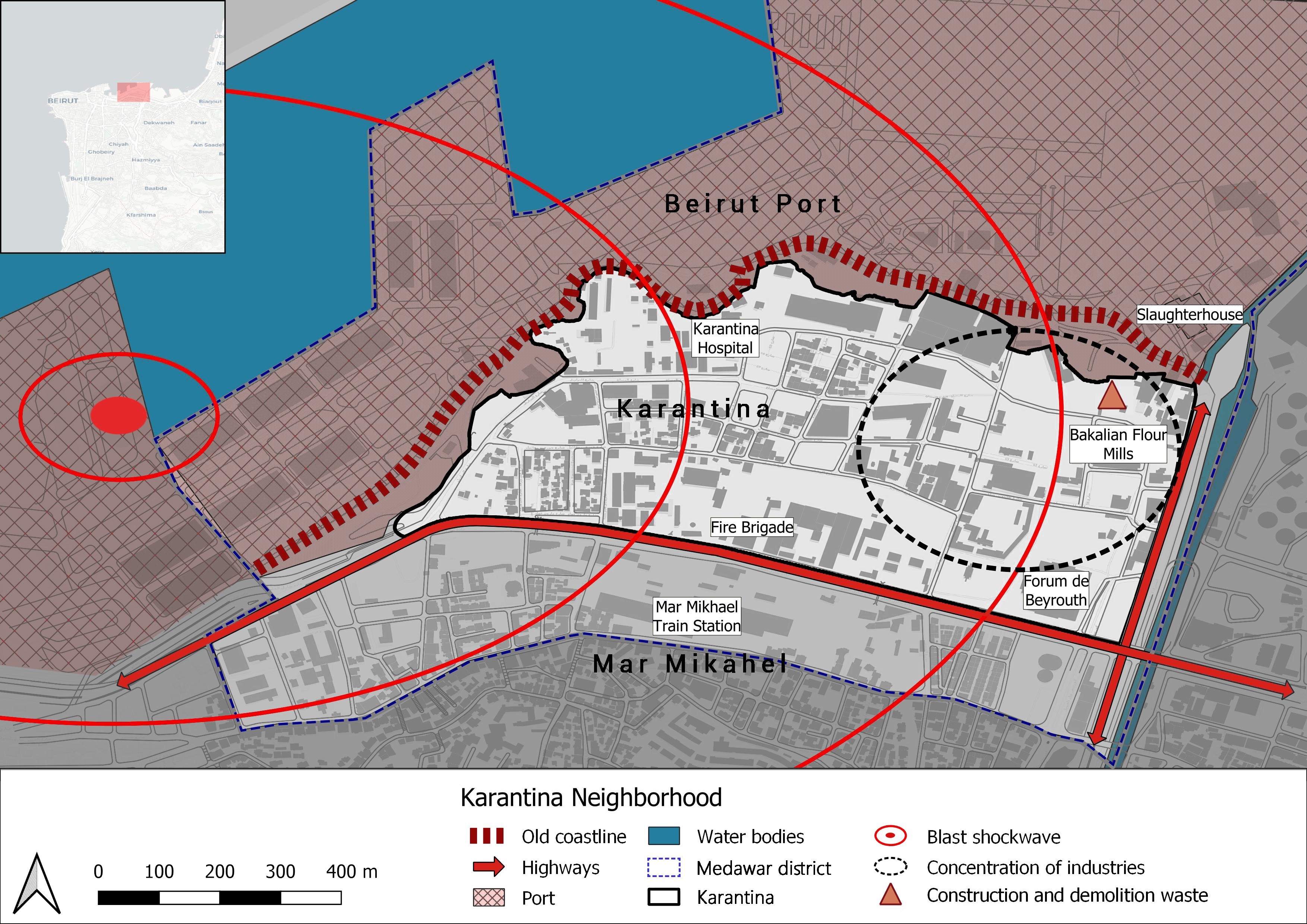

The area of Karantina encircled by the port and highway (UNDP)

Located on the periphery of Municipal Beirut, Karantina has long served as a refuge for minorities. The neighborhood is shaped by decades of war, migration, and exclusion. The construction of the Beirut-Tripoli highway on the southern side separated the neighborhood from the rest of the city; the port extended over the area’s coastline to the North; and the industrial activities developed on the eastern part. This intimidation of the residential clusters is further exacerbated by the contaminated river, the waste dump, and the industrial pollution. The residents, including a sizable community of Syrian refugees, are among the most disadvantaged in the city: low incomes, high unemployment rates, housing insecurity, and difficult access to basic services. The August 4th explosion worsened the pre-existing social despair and collective trauma. It deepened the mistrust of residents in public institutions, and triggered tensions between community groups.

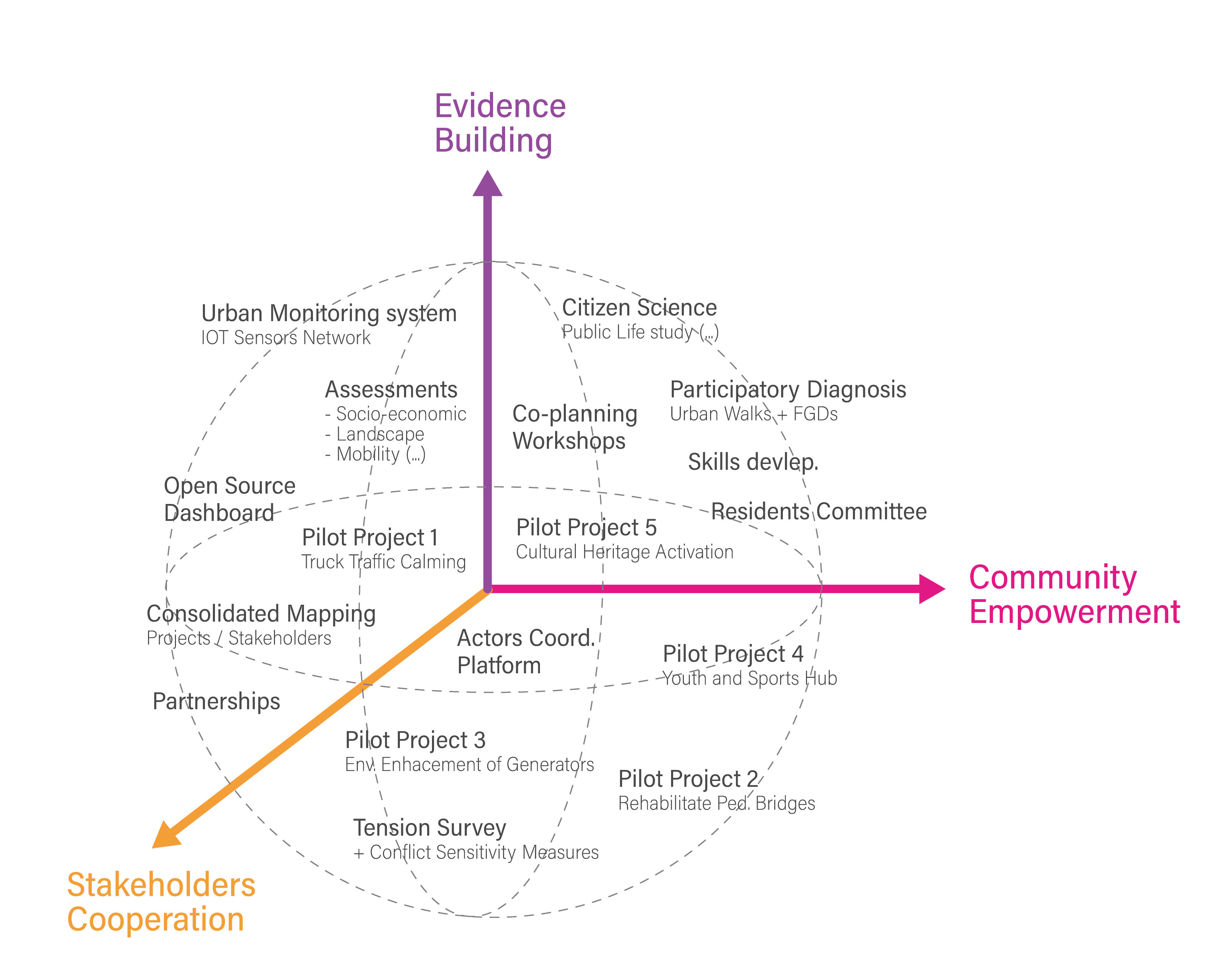

For all these reasons, and following the integrated emergency response, UNDP is actively working on establishing a recovery framework that can redress inequalities and contribute to a more inclusive and livable neighborhood. Rather than being a ready-made recipe for recovery, this framework is an incremental work in progress that stems from an ongoing engagement with the local community, public institutions, and non-state stakeholders. It builds on a continuous observation and mapping of the various activities on the ground, and a series of assessments that helps understand the complexities of Karantina’s physical and social conditions. So far, the framework has evolved into a process of three interconnected tracks: community empowerment, stakeholders cooperation, and evidence building.

The Neighborhood Recovery Framework: Three Interconnected Tracks (UNDP)

I. Enabling Active Participation in Recovery: The Restoration of Community Dignity

Beyond the usual consultation mechanisms that dominate the current planning practices, the local communities in the area affected by the blast need to be approached as active urban agents with the right and capacity to access information about their rights as city dwellers, the available support systems, and the ongoing plans affecting their neighborhood. They must be given the opportunity to identify and voice problems and priorities, discuss projects, and potentially participate in the inception, design, and implementation of solutions. They must also be able to organize collectively around shared concerns and interests. Recognizing the importance of these objectives, UNDP is undertaking the following initiatives:

- Enabling the establishment of a neighborhood committee, representative of the different social, economic, and cultural groups, to engage in the various decision-making processes in Karantina during the recovery period and beyond.

- Conducting Citizen Science-based research about the public life and public space, to build knowledge and capacities of local young people, especially women, about the social value of urban space, and to empower their critical thinking in relation to their environment.

- Facilitating a people-centered diagnosis and planning, which includes focus group discussions, urban walks, and co-planning workshops. This allows the prioritization of the community members’ experiences, ideas, and opinions.

- Implementing pilot projects as community engagement tools in-and-of-themselves. These projects, small in scale yet high in potential impact, allow effective participation of community members and cultivate a sense of collective ownership, therefore ensuring sustainability of solutions.

During the Urban Walk in the Khodor sub-neighborhood in Karantina (UNDP)

II. Facilitating Stakeholders Cooperation: Avoiding Duplication and Maximizing Efficiency

With the relative absence of public institutions on the recovery front, the affected neighborhoods continue to rely on NGOs and international organizations for reconstruction and aid. In Karantina, the abundance of actors on the ground is channeling much needed resources into the district. However, this opportunity has come with significant risks and challenges, which include but are not limited to: scattered efforts and projects overlap; inconsistent standards and criteria; restrictive budgets and deadlines; blurred lines of accountability and transparency; and the marginalization of public institutions. To avoid such trade-offs, UNDP is facilitating cooperation between relevant stakeholders, ensuring complementarity of efforts, fostering partnerships, and charting a mutual route for equitable recovery based on people’s priorities and available resources. This has entailed the following activities:

- Creating and operating the Karantina Coordination Platform to facilitate dialogue between a dozen parties representing different CSOs, international organizations, the municipality, and representatives of the local community. Until now, the platform has resulted in a shared plan for the improvement of public space and infrastructure. It has also encouraged creative partnerships and synergies between stakeholders, resulting in the development of multi-layered solutions.

- Developing and updating a consolidated map to keep track of the different plans and projects, to ensure complementarity, effectiveness, and transparency of the interventions. The map is regularly shared with the local community through the residents’ committee, and will be shared with the wider public on a dedicated web portal to go online soon.

Coordination workshop on street rehabilitation projects (UNDP)

III. Evidence Building: A Continuous and Hybrid Learning Process

Central to the neighborhood recovery in Karantina is the evidence-based planning which entails aggregating socio-economic geo-referenced, and other types of data to identify people’s multiple indicators of vulnerability and share knowledge among relevant parties. UNDP’s current approach to evidence in Karantina promotes a mixed methodology that combines sensor technology, human observations, and community perceptions. Evidence building is viewed as a collaborative endeavor that strengthens accountability and builds the capacities of public institutions. It is a co-learning process whereby small-scale pilot projects are implemented to test solutions together with the community, scale up successes and inform long-term decision making. To this end, the following activities are underway:

- Developing an urban environmental monitoring system based on an IoT (Internet of Things) sensor network to be designed, assembled, and installed in the streets of Karantina. The network will provide real time multi-spatial information and trends analysis on the varied factors affecting the urban environment, including air pollution, noise levels, traffic, and more. It will help identify opportunities for neighborhood improvement and will serve as an impact measurement tool for future interventions.

- Conducting Public Spaces Public Life (PSPL) surveys to understand how people use urban spaces and to evaluate how healthy, safe, inclusive, and conducive to economic vitality, these spaces are. The PSPL surveys will be conducted by trained community members and will be based on direct observations of the users of the public realm, with particular focus on gender and age factors.

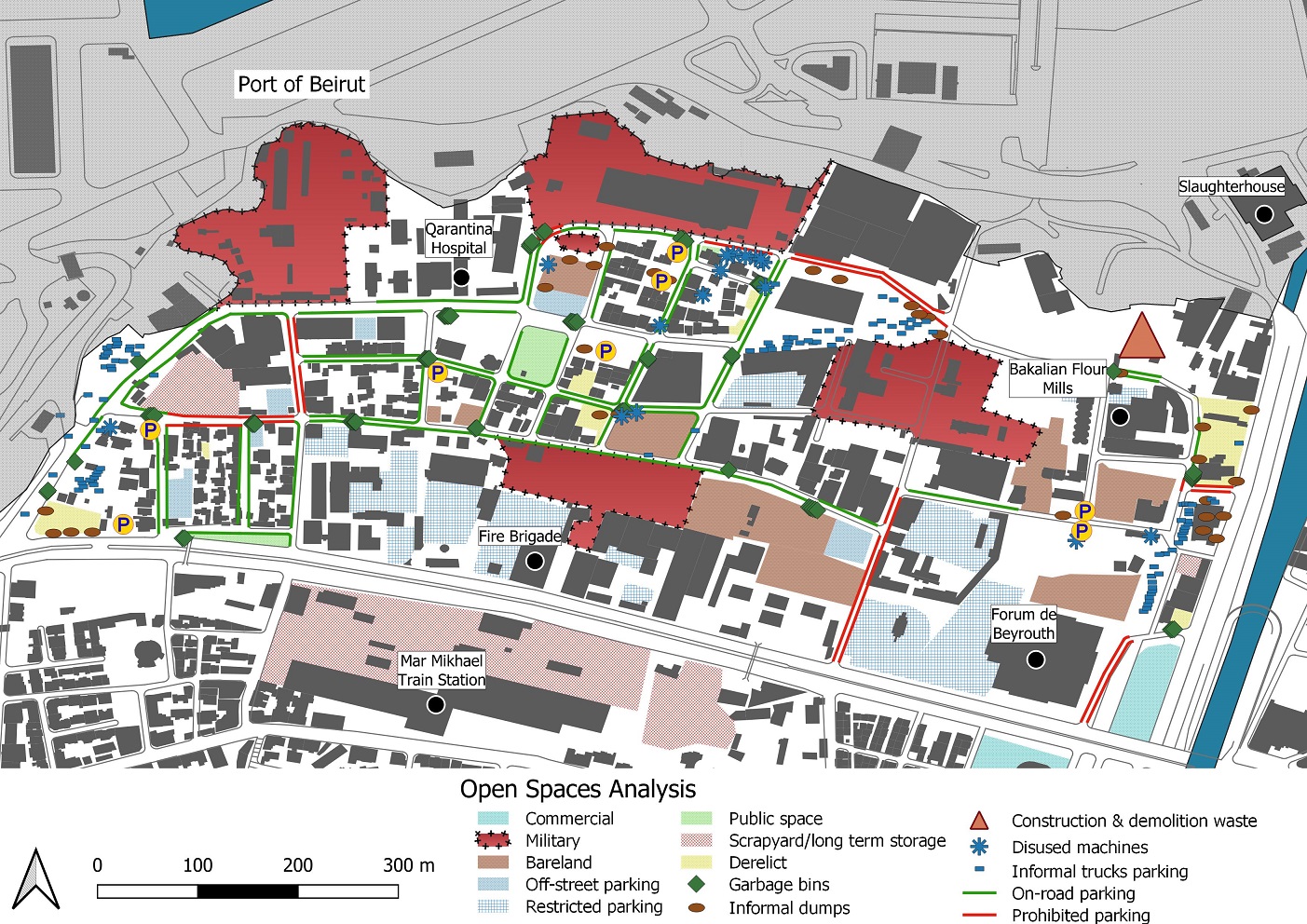

- Conducting a series of assessments to deepen insights into the urban system in Karantina. This has included an urban spatial analysis, a truck traffic and mobility assessment, a landscape heritage assessment, a socio-economic assessment, a local tensions analysis, among others.

- Developing a dashboard to capture the received data from the sensors as well as from surveys and assessments, and to map ongoing plans and projects. The dashboard will provide a cutting-edge analysis and reporting tool, making data accessible to the public and fostering collaboration between stakeholders.

- Registering the performance of pilot projects and document experiences, as part of a feedback loop to build knowledge about how suggested solutions fared on the ground, thereby improving the outcomes.

Site Analysis - Geo-referenced Mapping of Open Spaces (UNDP)

The Action-Oriented Planning: Balancing Processes and Results

Urban planning and development in Beirut are dominated by large-scale, often risky, projects that are bound with rigid budgets, donor requirements, and timeframes. These plans neglect the locals’ participation, feedback, or review because criticism is generally considered high-risk from a project management perspective. The threefold framework - community empowerment, stakeholders cooperation, and evidence building - sets the ground for a different way of planning for the city: the action-oriented planning. This consists of conducting tactical interventions and urban experiments that are low-risk, evidence-based and participatory, as a way of planning through action and learning. The interventions help 1) deliver quicker benefits for the community, 2) test solutions to inform decisions and resource mobilization; 3) refine and scale-up solutions based on continuous feedback, 4) engage the local community in the prototyping and ensure community ownership. This establishes a balance between the necessity of an inclusive, locally sensitive process on one hand, and the need for immediate improvement and development on the other.

Tactical Interventions Process (UNDP)

For these tactical projects to have a lasting systemic impact, they need to be guided by clear goals defined early in the planning process and updated along the way. Accordingly, we conducted a series of participatory diagnosis activities to identify long-term goals. These activities, coupled with the findings from the assessments, led to the identification of cross-cutting priority needs and problems, which can be grouped under one or more of the following themes:

- Safety and Security: People want protection against traffic and road accidents, theft, assault, and conflict. The Blast has exacerbated the already-existing sense of insecurity, affecting especially women and children.

- Accessibility: People suffer from the lack of direct and easy access to the city, long distances to major services, and from streets conditions that are unwelcoming to women, elderly, and people with disabilities

- Health and Environment: People suffer from high levels of air, noise, and visual pollution. The traffic, waste dumps, industries, power generators, and sewage conditions have caused serious health problems to residents and workers. Despite the abundance of open space, the urban environment offers very few options of healthy outdoor activities and encounters.

- Livelihoods and Affordability: Most residents in Karantina lack access to affordable healthcare, education, and other key services. They struggle with housing insecurity, very low income, and unemployment. Power cuts and water shortages are unbearable especially in summer.

- Neighborhood Character: People wish for a more attractive neighborhood image and reputation, an image currently associated with poverty and decay. This affects the community’s sense of belonging and deters economic opportunities.

Committee members discussing priority issues and challenges (UNDP)

As a result, several tactical interventions are being designed or implemented in collaboration with the community and partners. These interventions involve new physical and spatial models, social and economic programs, as well as innovative processes of coordination and governance. One of them, for instance, is the “Truck Traffic Calming Project”, an initiative that addresses the issue of unregulated heavy traffic and parking of trucks within the residential and commercial zones, which has caused substantial harm to the community: danger to pedestrians (especially children), noise, pollution, congestion, and damage to roads and sidewalks. Another tactical intervention is the renovation of the two pedestrian bridges that connect Karantina to Mar Mikhael. These poorly managed bridges were identified as critical locations for women’s safety, due to threats of theft and harassment induced by the spatial conditions and lack of lighting. The tactical project thus aims to renovate the pedestrian bridges and adjacent spaces to provide a safer passage for pedestrians, improving the neighborhood’s connections with the rest of the city. Other tactical interventions include the conversion of a car parking space into an innovative youth and sports hub, the establishment of a cultural heritage network and program, the reduction of emissions and disturbances emerging from power generators, and others. Some of these solutions will be piloted within the next few months, and will generate learnings to be shared with the communities and partners.

Port-generated trucks dominate the public space in Karantina (UNDP)

Conclusion

The path towards urban recovery in Beirut is a complicated journey. It needs time and resources and necessitates the strengthening of the weakened administrative structures and governance systems. It also requires active collaboration and consensus among stakeholders. All these challenges are far from being overcome. Yet, UNDP has decided to adopt a proactive strategy by willing to immerse in the neighborhood to understand the in-depth context and learn from past and current experiences. So far, this has led to the development of an agile framework that, despite the limitations, encourages the co-production of sustainable, locally-owned solutions, instigates continuous learning, and stimulates new connections and relationships that can potentially influence the paradigms in the planning and governance of the city. Indeed, the ability to scale up the solutions, either directly by extending geographical coverage beyond Karantina, or indirectly by informing the different existing systems, will further determine the extent of success of this endeavor. We therefore invite you to follow our series of articles to discover the unfolding of the different tracks and activities underway.

Locations

Locations