by Phan Hoang Lan and Nguyen Tuan Luong, Accelerator Lab team

Experimentation in action: the Good, the Bad, the Unexpected

February 12, 2020

This blog post is the second in a three-part series that shares Viet Nam Accelerator Lab journey applying innovation and experimental practices to help Da Nang city solve its wicked problems.

Following the field research we conducted in Da Nang, we gained a much better sense of what was happening in the city. We were then excited to start an experiment on waste sorting and put all the theories we had about systems thinking, lean experiment and circular economy into practice. With a fresh mind full of optimism, at first we thought, experiments are a bit like chemistry class. All you’ve to do is start with a hypothesis, add a little bit of design thinking workshop, mix in with some circular economy buzzwords, sprinkle with a pinch of behavioural insights data on top and voilà -- hypothesis proven!

Well... not quite. That’s rarely how things unfold in practice, as complex systems are constantly in a state of flux, your initial plans rarely survive the first contact with the local reality. As our first project, we had to balance between obtaining fast results to gain credibility while at the same time keeping the long-term systemic picture in mind. Case in point, our first 100-days experiment on a seemingly simple issue of getting citizens to sort waste correctly taught us a lot -- often in unexpected ways.

What the heck is a portfolio of experiments?

In the past, the notion of experimentation was once thought only reserved to white-coated scientists in their academic ivory towers or underground labs. Today, experimentation is gaining popularity in other fields like in business through lean startup and government policy-making (such as the Finnish Basic Income Experiment). But what an experiment actually entails is still foreign to the average person. For some people, experimentation is just another way of saying innovation, let’s take risks and try different things out. For others, it is a structured learning process committing to rigorous evaluation and empirical evidence. For UNDP Accelerator Lab Network, experimentation is perhaps somewhere in-between with an extra systemic thinking twist. We are testing ideas that aim to solve big sustainable development challenges, meaning not just a one-off experiment, but rather a series of experiments that build on each other (a.k.a: a portfolio of experiments). Finding out what works, what doesn’t, and more importantly, WHY? It means moving beyond performing innovation theatre (flashy effort to showcase new initiatives) to validate our ideas in a synergistic way that produces a systemic change.

Underpinning all this notion of a portfolio of experimentation is the humble realization that conventional one-off project intervention isn’t enough. Big sustainable challenges (like any of the 17 SDGs) are complex and interconnected; we need to respond to such challenges with a portfolio logic. In other words, we cannot rely on a single experiment or a group of disconnected projects to alter the unsustainable status quo, but rather our initiatives need to build on each other while taking the big picture into account. Now with the definition out of the way. We can talk about what we did.

The waste sorting experiment

Talking about experiments and system change is nice; doing it is a completely different matter. And one of our key discoveries was that the decision-makers are often happy to forgo the “evidence” and are keen to go straight into solution space and apply whatever they think is the right solution.

Initially, our partner in Da Nang, Department of Natural Resources and Environment (DONRE) prefered us to focus on their waste segregation plan, simply giving money to buy the needed recycling equipment. We proposed to conduct a lean experiment under one month to help them develop a good waste sorting model. But the officials we talked to didn’t really see the point of conducting such a short experiment to an obvious problem. We were asked questions such as: why bother with running experiments? What difference does it make at such a small-scale and short time? It's so obvious that people are not sorting waste because they lack recycling bins...let’s just give them those bins and the problem is solved. (Notice the underlying assumptions).

While this initial inertia was a challenge, it also gave us something to bite into as an experiment. We thought we could just test the above assumptions with the following hypotheses:

-

H1: "If we give people recycled bins, then they would start to segregate waste”.

-

H2: “If they still don’t segregate so much, then tell them to” (i.e. give people posters & flyers to tell them to segregate waste because that’s what “good” citizens do).

Phase 1 &2: Testing the obvious

With this as a starting point, our plans to work on waste management and running experiments in the field stopped looking like a walk in the park. We had to “legitimize” experimentation in the eyes of local government officials and, perhaps using initial experiments as a quick win, to build our credibility to work in the city on the system level change around plastic pollution. Even though we knew that focusing just on waste segregation would not be enough, we decided to start with this entry point to build relationships and credibility, while still keeping the systemic picture in mind.

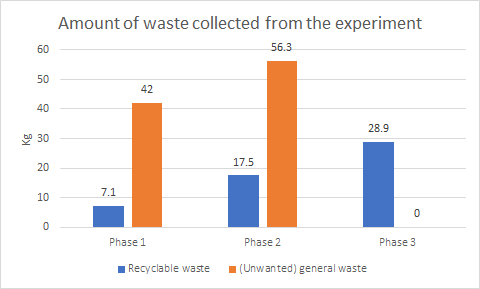

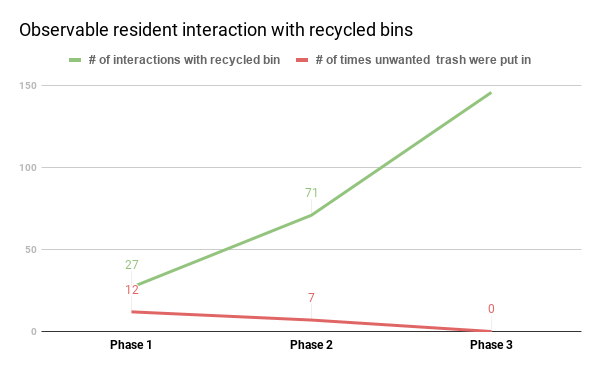

We were introduced by local officials to some apartment blocks in a poorer ward that was struggling with waste segregation. They didn’t have any recycling facilities and the existing bins were often overloaded. After the initial survey, we designed our first experiment in two phases, each lasting 10 days to test the hypotheses mentioned above respectively, in a basic setup similar to what DONRE would have rolled out in the area next year. The purpose of this was to measure the baseline of the current situation. So in the name of science, we set up some recycling bins and posters. Then we had a local person sit from 6 AM until 9 PM to observe some trash bins, weigh the waste collected and record citizen’s interactions with the bins.

Baseline: Providing basic recycling bins -- yellow recycling bin on the right

For 20 days, we observed people interacting with these recycling bins. Guess what? People didn't really use the bins! They either happily ignored them, used them for general waste, or even more so - complained about them! Moreover, we saw the amount of wrong waste (general waste) put into recycling bins kept increasing. So our first learning comes from actually invalidating the hypotheses of the government. Some people would think this was a negative result. Think again! With all the budget set to be spent on infrastructure that would not be used, our first big result was to save public money from being wasted -- while we spent pennies on our experiment.

With the initial hypothesis debunked, we were intrigued to learn how we can actually change people's behaviour? Thus we added an additional phase to our experiment.

Phase 3: Testing the unknowns

A desk is a dangerous place from which to view the world. John le Carre

From the baseline phase, even though we invalidated the initial hypotheses, we actually learn more about the "unknowns" (Things we didn’t knew) . By observing people’s interaction with the recycling bins (which should only collect paper, plastic, and metals), we learned that the current bin designs made it too easy for people to throw the wrong type of waste in. It has an easily openable lid and no mechanism to stop unwanted waste. Moreover, once someone threw the wrong waste type in, other people just follow them and keep putting in more wrong waste. The bins then become dirty and no one wanted to use it for clean recyclable waste anymore. To paraphrase, BIT’s language, the current set-up made wrong behaviours too easy and too social!

We learned that the designs of the current bins don't work but we didn't know which ones work. Through our local solutions mapping, we knew that there have been different types of bins being used in Da Nang for waste segregation, one of which is a very interesting local solution that the women union had designed and piloted, and we thought it can be adapted to better fit with the apartment buildings. The new bins are see-through (transparent), easier to clean and have a look that people find pleasing. Obviously, this is not something you would know without watching the actual behaviour of people.

Design of the recycling bin: existing local solution on the left vs. our adapted solution on the right

For another 10 days, we tested replacing the old bins with these new ones and the main hypotheses were that: (1) if the new design of bins has small enough holes (to fit recyclable objects but not enough for a general trash bags) then people are less likely to throw wrong waste into the recycling bins; and (2) if the new design of bins makes it easy to see the waste thrown inside, then people will be less likely to throw wrong waste into recycling bins.

Tallying up the result

After we processed the data in phase 3, we found that the results exceeded our own expectations. The number of the wrong type of waste collected went from increasingly high to practically zero, and the number of people using bins increased more than 5 times compared to the baseline. Over 90% of the people surveyed in the experiment agreed to recommend the city government to apply this model to the city-wide scale. Informal waste pickers stopped trying to pick recyclables from the bins but bought them in nicely sorted out piles from the apartment’s communities. Most importantly, the Government now had a viable option to invest its waste infrastructure money in!

Now take a step back and you see a completely different value proposition from the Lab in public policy design and delivery. Our quick experiment and related research helped understand human behaviour, debunk “failed” solution, identify field-tested prototype and adapt it so that it becomes a scalable option. We hope to see this experimental practices to be more common in future public policy design.

The unexpected learning

Among many valuable learnings from observations of people’s behaviours towards waste, some were quite unintended and interesting at the same time. Particularly, the two pairs of apartment blocks that seemed, in the beginning, to be similar are actually not so. Residents of one pair of blocks always disposed of waste more correctly than those from the other. Being curious, we talked to a few apartment residents and learned that the community leader of one pair of blocks actually served as a better role model for the blocks’ residents. He often woke up early and swept the whole block’s backyard and also installed self-made messages on the walls to raise people’s awareness about waste segregation. None of that was practised by the other pair of blocks’ community leader.

The residents also shared that the “worse” performing blocks had some households with alcohol addicts and gamblers that rarely adhere to social practices such as waste segregation. This might make other households feel less motivated to carry out correct waste segregation.

So we learned that community leaders and peer pressure can play a big role in influencing people's behaviours and as such is an important asset to be part of an effective behaviour change initiative!!.

Furthermore, we noticed a social factor that the government didn’t account for when making waste segregation policy - the informal waste pickers (IWPs). In reality, these IWPs have always been an integral part of the waste collection system. They usually buy value waste from households or scavenge it in general waste piles. In this experiment, we observed that at least 3 IWPs came every day to look for valuable waste from the general waste containers. So, even if our experiment result successfully changed apartment residents’ behaviours, the next questions are: How are IWPs affected by this change in waste management model? And how do we make it up for them if they’re the one losing out from this change? Looking further into policy advocacy, any waste management planning should consider all stakeholders, not just the formal actors, but also informal ones like the IWPs.

Action speaks louder than words: using small wins to achieve mindset change.

Although small in scale, one of the most valuable learnings from this experiment is that we need to be persistent and cannot be discouraged by the government’s initial scepticism. One of the government officials who showed the most scepticisms in the beginning, now says that he cannot wait to have Accelerator Lab’s involvement to help the government create more experiments to test other assumptions in the waste segregation area!

Back to our initial worry that the experiment might be too small and cannot help us tackle system change, this initial government’s appreciation gave us much more assurance to continue our work. We realized that one of the best values of quick win experiment is the initial social capital that we gain, which can lead us to roll out our system approach much more smoothly with the government in the future.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In our next blog and final blog of this series, we will zoom out from the ground action and put on the big picture lens. Don’t miss how we use the Systemic Design tool to radically change how policy-making is made! Big shout to Alex Oprunenco -- our partner-in-crime -- for his expertise, passion and close support throughout this intense, but rewarding ride. If you want to learn more about how to conduct an experiment or collaborate together with us in Da Nang to tackle the waste issue, feel free to reach out to us at nguyen.tuan.luong@undp.org and phan.hoang.lan@undp.org

Locations

Locations