by Luong Nguyen, Head of Solutions Mapping, UNDP Accelerator Lab in Viet Nam

The Anatomy of Social change -- a just transition to sustainable development Part 1

December 30, 2021

A well facilitated space is key for creative container

Around the world, UNDP is innovating to push the boundaries of sustainable development by embedding social innovation ideas into policy-making and community building. This blog explores What large bureaucracy can learn from social innovation movements toward system change? What it means to be part of a movement for change, making sense of the insights, and what it could mean to others who want to step into the movement.

Crises as a catalyst for change movement

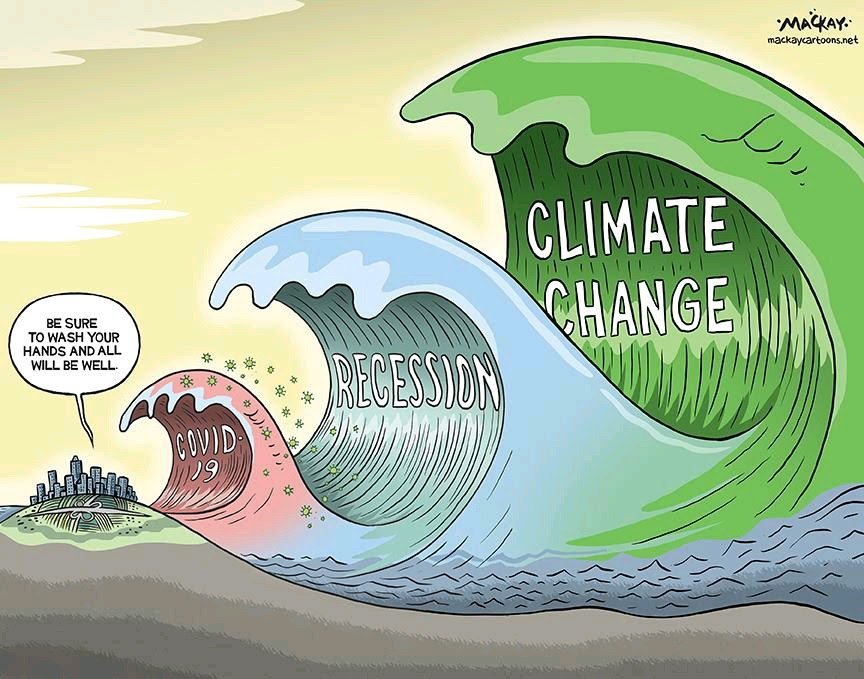

As we move into the Decade of Action, what began as a wave of health crisis last year, COVID-19 pandemic has quickly shown the vulnerability of our social system such as inadequate healthcare and exacerbated inequality (the poorest households being most affected) threatening to undo the progress we have made on 17 SDGs. Yet, behind the current COVID crisis, the recent COP 26 reminded us of an even larger threat in the form of climate change and related issues such as the growing plastic waste crisis, global inequality and biodiversity loss...This shows the interconnected nature and vulnerability of our systems, seemingly overnight what started as a health crisis became an economic crisis, a social crisis, and an environmental crisis all at once.

While COVID is still on full swing, other crises are not on hold (source: http://mackaycartoons.net/)

As UN chief António Guterres warned: the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are falling “disproportionately on the most vulnerable: people living in poverty, the working poor, women and children, persons with disabilities, and other marginalized groups. Similarly, the climate change crisis is expected to have the most impact on people least responsible for causing it. In almost every crisis, marginalized and vulnerable communities, low income countries, informal workers, indigenous communities, often face the worst consequences due to their already existing precarious status. So not only do we need to address climate change, but we need to do so in a way that is just and inclusive to those most affected.

According to The People’s Report, a global survey of 17,000 people by Catalyst 2030 , found that:

-

64% of respondents say that they are experiencing climate change in their daily lives.

-

50% of respondents say they cannot trust their government leaders.

-

51% report worsening mental health since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

34% of those under 25 years of age would not choose to raise children in their communities.

Projections by the Social Progress Imperative, even under the most optimistic assumptions the 2030 targets won’t be met until 2082. So why do our current institutions seem to fall short? Even with millions of dollars in funding, an army of employees, and political leverage, many of our institutions struggle to meet established goals, let alone changing from “business-as-usual” to something more sustainable and innovative.

What large bureaucracy can learn from social innovation movements toward system change?

Let’s say you (like me) work at a large institution and want to change the world, where does one start? To those of us who work in large organizations such as government, multinational corporate and intergovernmental organizations, changing the world, a nation, or our local community can sometimes feel like an endless uphill battle. With a laundry list of competing tasks and directives from multiple stakeholders. Maybe you look online at some tools and definitions such as social innovation to help you start and make sense of it all.

Perhaps few words are as ill-defined as innovation, adding “social” often confuses people more. One online search at “what is social innovation”, you will be presented with an endless amount of definition, most results talk about solutions and problems, some processes and products. Only one mentions the inherent communal aspect of the term, identifying social innovation as: “To strive for something together”. This can be seen as another way of saying a group of people working toward a common goal -- a movement.

Issues like environmental pollution, climate change, circular economy transition are incredibly dynamic and complex, involving a myriad of factors, actors, and circumstances. They demand a more fluid and adaptive approach than conventional top-down institutions tend to offer. Social innovation isn’t just about providing new products and new services; it’s about changing the underlying beliefs and relationships that structure the world.

Many of today’s large bureaucracy plan, manage and implement interventions in what can be described as a linear, mechanistic logic (e.g: The Logical Framework model). In this worldview, influenced by early industrial age management philosophy, a manager would often self-assume to be objective, scientific or ‘neutral’. They see the world as a machine, where there are inputs ( resources, capital…) and outputs (product, services…), often expectating a high degree of certainty and accountability in projects initial expectations and implemented results. Generally speaking, bureaucratic systems often require people to think in this linear (logical) fashion, often ignoring or invalidating those who think in other ways. There is a strong drive toward uniformity and conformity in the name of efficiency. In today’s VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous) world, such approach is increasingly showing its weakness, failing to cope with complex, interlinked issues.

System change -- is social tipping point possible?

In response to crises, all across the world, many grassroots movements are forming to advocate for change around social issues. Movements such as Friday for Future and Extinction Rebellion where young people are banding together advocating for climate justice or Black Lives Matter and Stop Asian Hate social movements on racism. But one might ask, how can movements led by disparate groups of people possibly change the world?

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has. -- Margaret Mead.

Greta Thunberg and Friday For Future Movement (source: https://time.com/5918448/greta-thunberg-coronavirus-climate-change/)

Following the results of the last COP26, many commentators deemed that the planet is already close to a point of no return, and is too late for incremental change. Our hope for survival as a species might depend on the mobilization of a much wider civil movement. If we can mobilize just 25% of people, we might be able to flip social attitudes towards the climate. Highly decentralized and self-organizing movements such as Friday For Future, were able to mobilize large numbers of people, with little financial resources or predefined agenda, yet were able to put climate change into popular discourse with a sense of urgency. Meanwhile countless scientific reports and politicians' rhetoric struggled for years to gain mainstream acceptance on the same issue. This type of movement provides an alternative path to fill the gaps in areas that the current predominant institutions fail to do. They operate in radically different logic from our existing institutions; they are not the results of top-down decision-making but instead reflect principles of self-organization at the heart of many living systems and social innovation movements.

Managing expectations and redefining success

Since Accelerator Lab founding in 2019, we’ve been testing social innovation approaches to accelerate learning in sustainable development. As an innovation unit, we have the pressure to both do things differently AND conform to existing norms and regulations. In many organizations, there is often a large gap of expectation between what people think innovation is (often new product/ideas) versus innovation actually is (a practice).

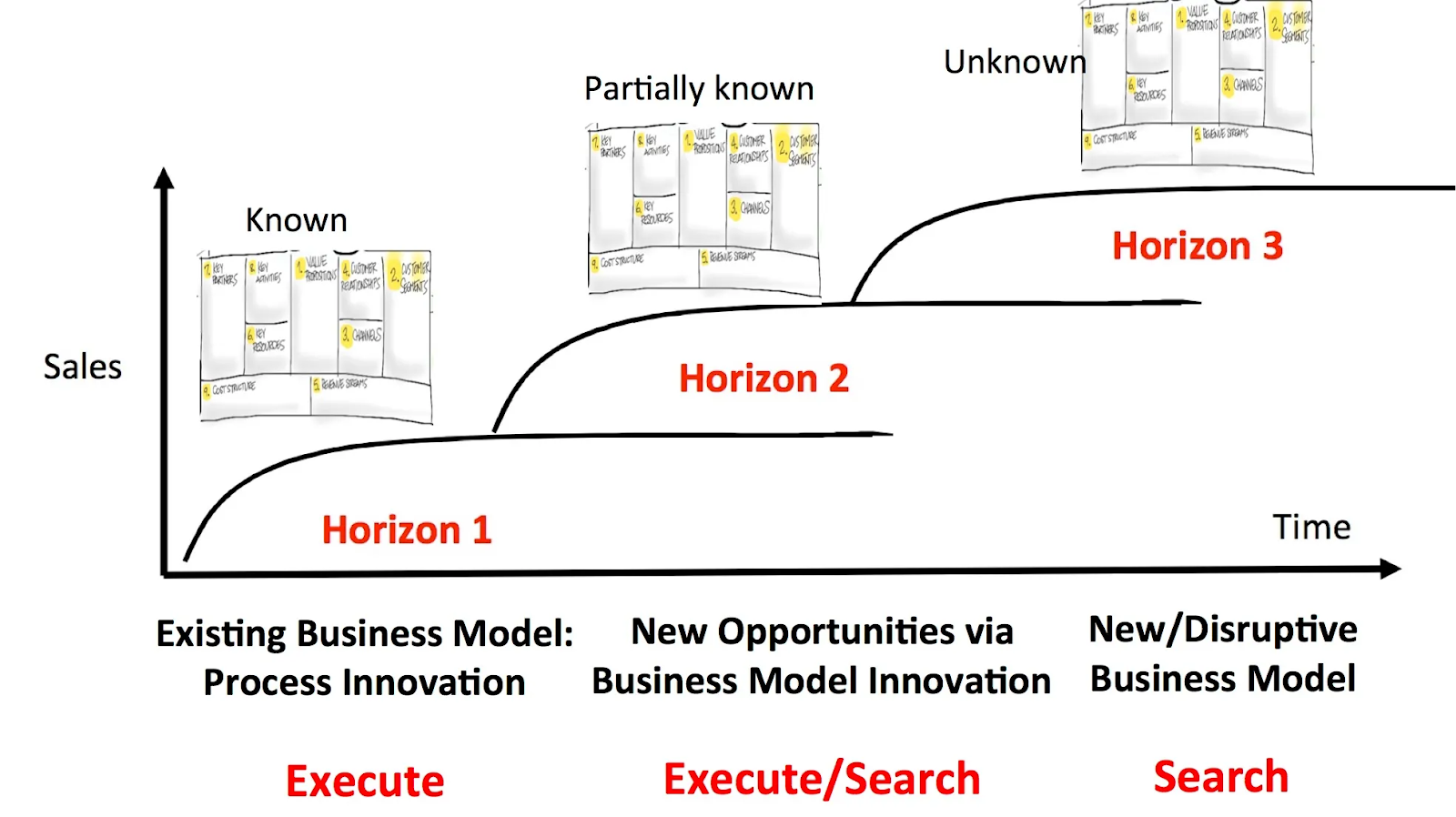

For example, my title is Solutions Mapping, and often colleagues would expect I know many off-the-shelves solutions ready to plug-and-play in ongoing projects. Yet much of my work (and other mappers) has been focusing on understanding the problem space where skills such as facilitation, deep listening, ethnography, and movement building are valued. These offerings are qualitative by nature, much more difficult to measure and do not always conform to traditional Key performance indicators (KPIs). To take a page from Lean startup playbook, most corporate departments and public agencies today are fully preoccupied with executing predefined agenda, this often comes at the expense of exploring new/disruptive ideas.

Lean Innovation Management – Making Corporate Innovation Work (source: https://steveblank.com/2015/06/26/lean-innovation-management-making-corporate-innovation-work/)

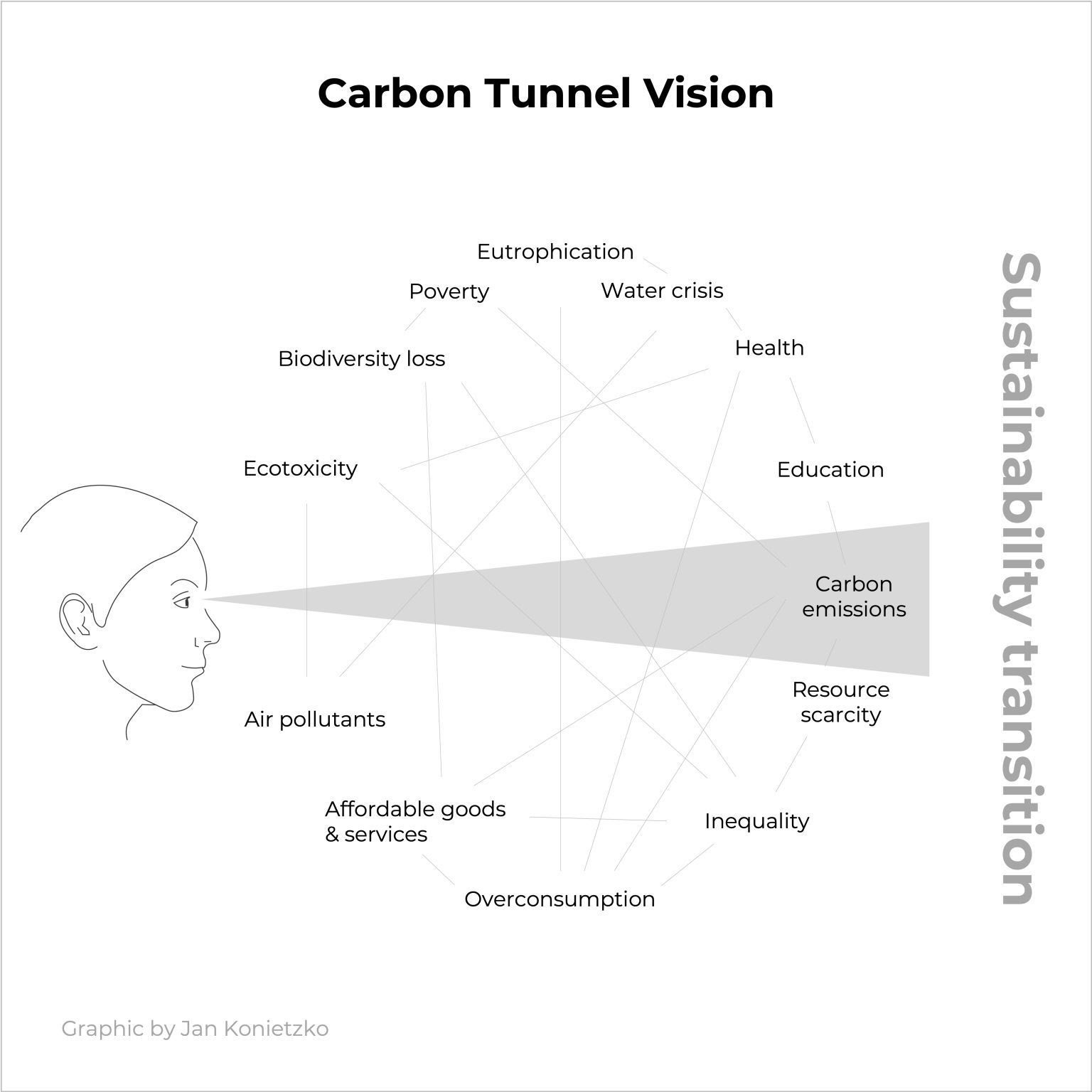

One interesting question to ask here is should innovation focus on “getting more of the same” (known) or “uncovering new or hidden opportunities”? (unknown). If one look at our corporate KPIs you would find that there are many quantitative indicators such as: % delivery, revenue, resource mobilization… or high-level indicators Country Programme Document such as # tons of CO2, % of seats held by women in the national assembly. Upon closer analysis of these indicators, one can find that they are loaded with the assumptions that the goal of development is often to be/do/get more and be/do/get bigger. Much of our resources are directed toward producing quantitatively measurable goals that are known. Yet these KPIs can be limiting, tunnel vision even, to our organizational “definition of success”. This can lead to a tickbox culture with an overemphasis on quantity (what can be counted) as more valuable than the quality of the work.

From an innovation perspective, the value of innovation is often in discovering the unknown to solve existing problems. In my experience working within the system and together with programmatic colleagues, I’ve witnessed and experienced incessant pressure to meet KPIs and deliver so-called quick wins. Where things that can be counted are generally more valued than things that cannot, for example numbers of people attending a meeting, newsletter circulation, money raised and spent are valued and reported more than quality of relationships, democratic decision-making, ability to constructively deal with conflict, morale and mutual support. Making sure that our work can add up to big numbers is often a constant source of anxiety and fear that limits our imagination and potential. A singular pursuit of quantifiable KPIs often disconnects us from our ability to listen and be present, which are the source of creativity, of connection, of growth. In a traditional project, much of our staff's focus and time are spent on fulfilling the above KPIs, leaving little room for exploration and creativity. One could argue that this is where the value of an Innovation Lab using social innovation approaches, where there is freedom and flexibility to explore and probe the bigger picture in a way that expands our “definition of success”.

Collective intelligence need respecting differences

Together with our programmatic colleagues, national partners, we’ve been involved in designing and implementing Danang Circular Economy Hub (DCEH), Vietnam Accelerator Lab Community (VALC), Circular Economy Training of Trainers. Though they differed in locations, time and partners, yet these initiatives shared an intention: to invite local participation through collective intelligence to build community and facilitate a movement for change.

The social innovation process was similar. These initiatives kick-off with an intensive bootcamp/workshop (designed in Social Lab fashion), which helps to stimulate a rich conversation, with diversity, allowing the community to sensemake around a common topic. A rich conversation needs the right environment though, especially if you want to invite diversity and inclusive participation. For instance, in the VALC program, there were lawyers and bankers sitting next to artists and freelancers; we had university students along with those who had been teaching for 16 years. To ensure a welcoming space for all, we co-created principles of being together, as well as established practices like the Circle Practice so that everyone can be heard and seen. “This bootcamp was a space of connection, openness, and diversity,” shared Ms. Nguyen Phuong Thao, a member of VALC. “There was so much difference, and yet people still feel safe to be open with each other. That is like...for me I’d call it magic.”

During the program, aside from the traditional teaching and presentations, we also hosted conversational processes that allowed the group collective intelligence to emerge. With methods like Open Space Technology, Collective Story Harvest, and World Cafe, the participants had the space to be in conversations and gained wisdom from the collective intelligence.

Across time and culture, storytelling and conversations are essential for the meaning-making and creating ownership in a community

This spirit of collective intelligence and inclusive participation can even be brought on to the online space (as many of us are forced into during COVID time). Despite the challenge of connecting through digital platforms, today we have powerful tools to facilitate these conversations through online platforms. In just over a year, we have been quite proficient in helping partners and colleagues using methods and digital tools such as Mural, Slido, Zoom etc..( often in combination) to achieve similar results as an in person brainstorm would.

Loaded words like Circular Economy or Sustainable development more often than not alienate people. Socializing big concepts with the community in a way that makes sense to them is crucial.

So what changed in the end?

As a popular quote attributed to Gandhi goes “Be the change you wish to see in this world”. Both innovation and sustainable development are change management processes. The challenge is we all wish something to change, yet not everyone is clear what is the change we wish to see in this world. So an important question we often need to come back together, and on a personal level is “what do I/we want successful change to look like?”.

If I take the lens of our corporate KPIs, these community driven initiatives above by themselves perhaps don't look like much. I would feel inadequate, not enough, and feel pressured to do more and bigger things. Yet if one is willing to dig deepers, one could see that beneath these initiatives are planting the seeds for change. The change happens in the quality of the conversations and relationship between stakeholders, new insights, stronger connections, and inspiration that are forming when movements take place. Imagine how fulfilling development work can be when we can let go of anxiety and fears to perform for the numbers. It might just open our ability to show up fully as human beings. After all, shouldn’t development work be more about human beings than human doing?

Stay tuned for the next part in the series of The Anatomy of Social Change to learn more about social innovation and recommendations that can help sustainable development practitioners.

Locations

Locations