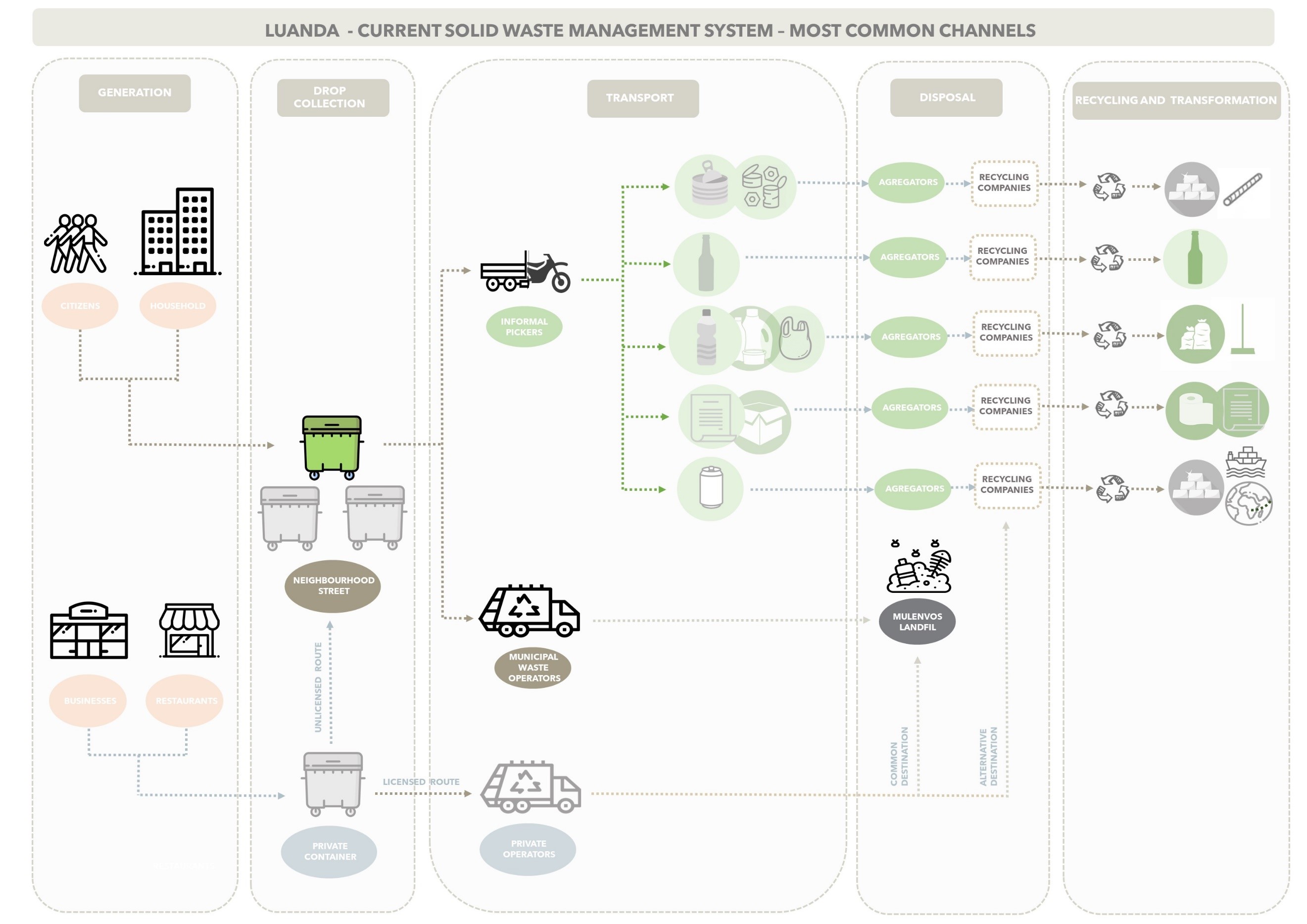

Figure 1: Infographic, Luanda Solid Waste Management System – common channels © Accelerator Lab UNDP Angola

Navigating the formal/informal narrative in 100 Days

Well, If someone told you had 100 days to generate knowledge on a specific subject, you would think that, it’s more than 3 months, so plenty of time. Right? Well, the thing is: to change a system you must understand the system.The waste Management System in Angola is quite complex since it operates through, to some extent, a fragile set of relations tied to social, political and environmental agendas which are constantly changing. To fully grasp the mechanics of it, you need to dive deeper and try to see what lies underneath the surface.

We started our process by reaching out to the obvious suspects, from state institutions, to well-known players and commonly known connections. We scheduled meetings and slowly started peeling the onion. We quickly realized that traditional data, as we might call it, would not be something we would be using much… And in Angola we still have a long way to go in order to collect relevant information on waste production and composition from the so called “formal” waste management chain. If we look at the alternative channels, it gets even more complicated.

We believe that it is important to state that we are not supporters of the formal/informal binary for many reasons. Mostly because we know things are far more complex than a 2 sides of the coin situation, but also because very often these “realities” are far more intertwined and interdependent than many expect, and they are frequently analysed through a legal/illegal lens, missing out on other elements that should be considered. However, in Angola this is usually how the story is told and this binary narrative is commonly used to frame development discussions both in the political arena as well as in our day-to-day conversations in social settings. So, this is how, for the purpose of this post, we will frame our learnings on the waste management system.

In a city where the majority of the population lives in areas some might consider “informal” (unplanned, with no infrastructure, lacking basic services) and depend on an economy also considered “informal” (unstable makeshift opportunity businesses, no tax collection or legal registry), we should be looking at “informal” as the norm and not the exception, and creating policies for the norm, not the exception. In Luanda, the Waste Management System has two main channels and there is a third alternative private channel running for businesses and companies.

The main “formal” channel can be characterized by the collection of general domestic mixed waste from public street containers by companies which are legally tied to the local government by a service contract, which limits their operation to specific areas/municipalities. In this system, waste is not differentiated and is taken to the Landfill where it is weighted and deposited with no specific treatment or transformation. In the last years, the companies providing the service have been changing frequently. New public bids usually open whenever there are changes in the mandate of the local government at the provincial level. The model itself has also been changing constantly, from a single company that would cover the entire city to several different companies covering limited areas. In order to withstand frequent delays in payment without compromising the provision of services in a regular effective way, companies need to have the capacity to rely on their own financial pillow. The coverage of the collection system is also quite limited, as many secondary streets are no covered, so in many places only main streets have collection points.

Figure 2: Pile of glass to be recycled at Vidrul © UNDP Angola / Judite da Silva

Recently the government established a fee to be paid by citizens as a contribution to the waste collection service. This fee was associated with the electrical bill, but the model failed and was dropped probably due to a lack of adherence from citizens, as a response to the inefficiency of waste collection in most parts of the city. In the past, there was also significant infrastructure investments in waste transfer stations/buying facilities, where citizens would sell their mixed waste. This model (2007) also failed and since we have not researched on this model specifically, we are not able to share the specific reasons that led to its failure.

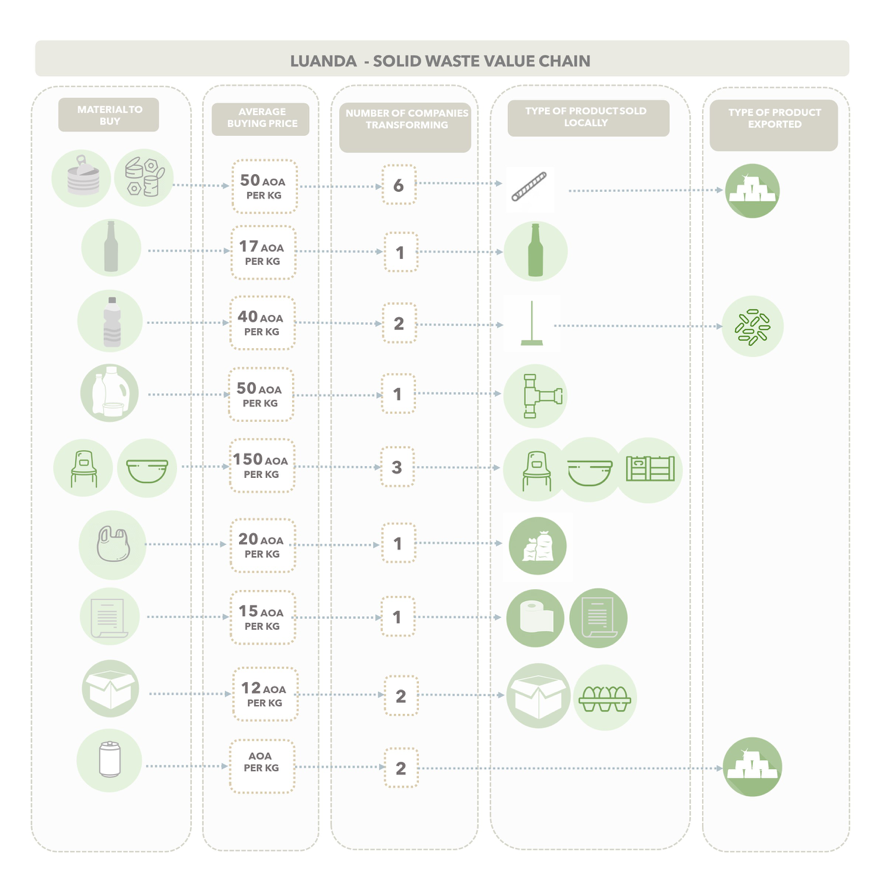

The “informal” channel for domestic waste is far more complex starting when waste-pickers (adult, elder, children and youth) go through mixed pile of waste in public containers and select plastic bottles and packages, aluminium cans, glass bottles, cardboard and paper, and sell it to “aggregators” who usually store the waste in their yards until it reaches a relevant amount to sell to recycling companies. Since there is no regulation on prices, there is no assurance on the fairness of the prices stipulated by the recycling companies.

For businesses, the law requires to have a licensed waste management plan that assures the collection of the waste by a private operator payed directly by contract. Although this is the law, many businesses, specially cafes, restaurants and shops still drop their waste in the street containers. Most private operators that provide private collection services to companies, still take mixed waste to the landfill, only few separate and send specific materials to recycling companies.

Speaking of recycling companies, when looking at the current market we were surprised by the amount of companies that are already transforming different kinds of waste. We have mapped so far around 20 businesses all in Luanda. Although we are not able to assure all are legally registered with an adequate licence the truth is that they are contributing significantly to a reduction on the waste on the streets. Currently, it is getting harder to find a glass bottle, PET bottle, aluminium can, cardboard or scrap metal lying on the streets for too long. Their financial value has been uncovered, having, therefore, waste-pickers quickly collecting one of those valuable materials and send them to a specific destination.

Figure 3: Infographic, Luanda Solid Waste Value Chain © Accelerator Lab UNDP Angola.

Looking at the information we have gathered, we are now able to draw the value chain of different types of solid waste, from generation to destination. By doing this we might understand where the main gaps are and identify “room for manoeuvre” which is the first step to generate a series of hypothesis. For the scope of our work, hypotheses are defined as the foundation to design a portfolio of experiments in order to test many possible solutions. Which in turn will allow to simultaneously “press” many different buttons and create systemic change.

Locations

Locations