UNDP and FAO assess agriculture and water systems to build the resilience of farming and pastoral communities

Finding climate solutions for Ethiopian farmers

July 7, 2023

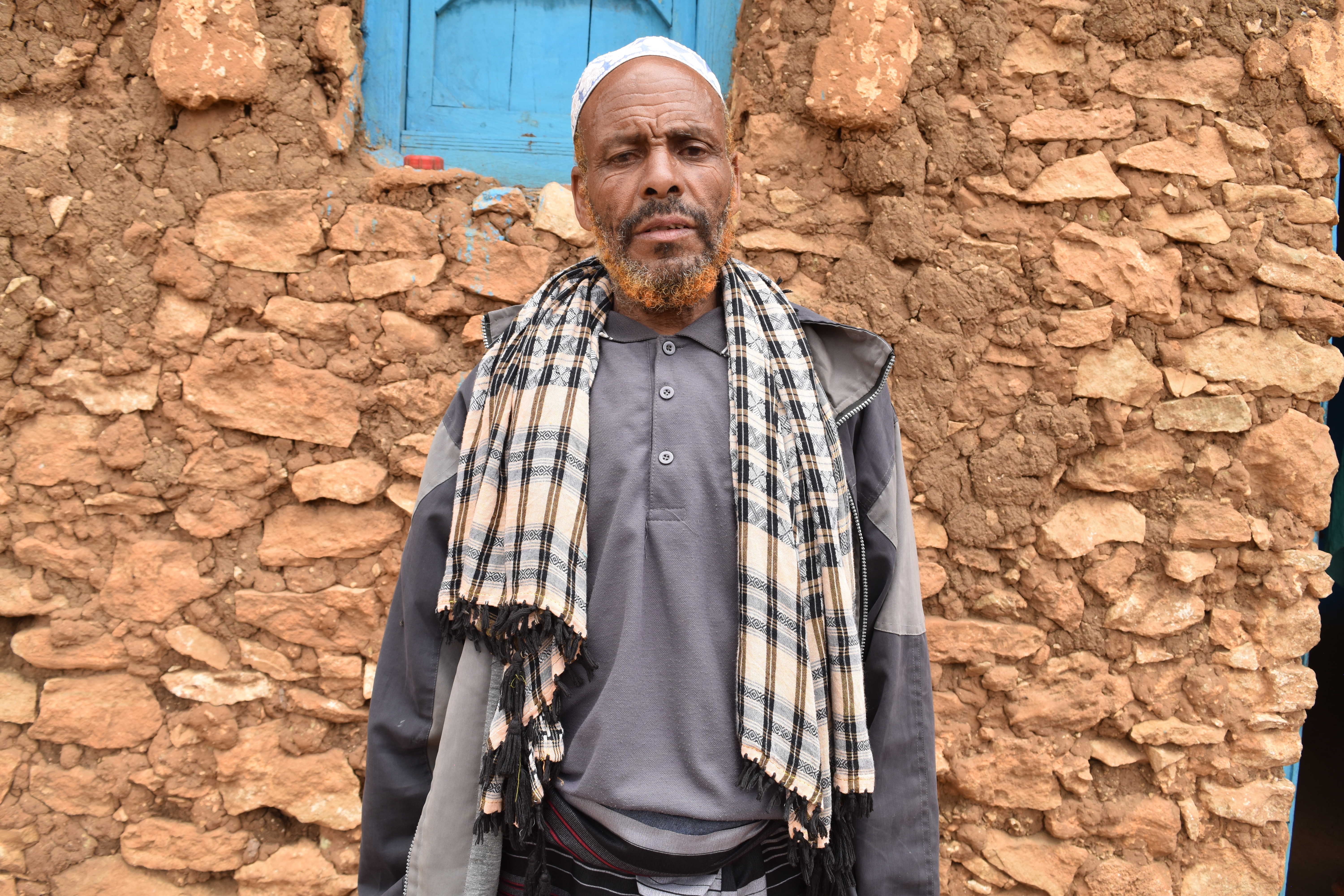

Redwan Sabet, farmer, with some of his children.

Nestled in the Horn of Africa, in the eastern part of Ethiopia is the region of Harari, known as the midlands for its semi-arid rolling hills with terraced farms.

In the late-morning, residents of Sofi woreda (district) arrive on foot with jerrycans to their local freshwater spring. Many young women and girls collect water here for their household needs, livestock and crop production, such as potatoes, onion, tomatoes, coffee and Khat (Chat). Some women bring multiple cans fastened to the backs of donkeys to ease the long commute home afterwards.

Irrigation springs like the one located in the Lugo watershed are a lifeline for the smallholder farming families living in the area, and, for some it’s the nearest water point from their home.

Eighteen-year-old Derertu Hohammad explains, “We used to travel about three hours for water, but now we can get water within an hour of travel here.”

Worldwide, women and girls spend an estimated 200 million hours — every day — collecting water, according to UNICEF.

“The volume of water decreases in the dry season,” Derertu continues. “It is difficult to get water for drinking and washing during this time. A jerrycan of water is not enough. So, we need to go to the stream several times a day to fetch water for household consumption and our animals as well. Livestock feed shortage is also a challenge. We are usually forced to buy animal feed. I would love to see activities that can reduce women’s burdens.”

Derertu lives with her nine family members. The family’s livelihood fully depends on agriculture. “We have a very small farmland where we produce crops and vegetables, and we use most of the products for our own consumption. Sometimes the food we produce is not enough for our family, we only produce for a maximum of four months and cover the remaining time of the year through the SafetyNet program.”

Water availability and drought are pressing issues for farmers in Harari because water is intimately linked to food security. Farmers across Ethiopia still remember the devastating effects of the drought in 2015. With a high dependency on rain-fed agriculture, farmers in the region are particularly vulnerable to the unpredictable rainy season between June and September and prolonged dry months.

“Due to the rainfall shortage last year, our crop production is not enough this year, and this has caused a food shortage for us,” explains Redwan Sabet, a family farmer and father of eight children. Living down the road from the spring, Redwan and his wife Sahara produce chat, sorghum, maize, and potatoes on their farm. Sahara is proudly responsible for their 43 hens and poultry production and everything they produce goes to feed their family.

In Ethiopia, 60 percent of households depend on agriculture as their main source of income. The regional government in Harari, with the support of development partners, have built wells, developed springs, and constructed ponds to improve the water availability of this community. So far, around four micro-watersheds have been established in the Kebeles of Sofi Woreda.

Across the street from the Lugo spring lives farmers Eshetu Tesene and Yusuf Omer, and their farm is their sole source of income. “I have a small plot of land, which is less than one hectare, and I produce maize, sorghum, and cabbage. We usually use the products for household consumption and sell only the remaining ones. This season, there is not even enough for household consumption,” Eshetu shares.

“When the environment keeps changing and the rainfall season disrupted, there is a high crop failure, feed shortages, and livestock deaths. Thus, we appreciate the support of different types of improved seeds and fertilizers which help us to produce better in the coming planting season,” Eshetu added.

The Lugo micro-watershed is one of the watersheds located in Sofi woreda and directly benefits 500 households. In this area, every household contributes 50 birrs monthly (US$ 0.92) for maintenance of the spring well and water canal, and security services. The watershed is managed by the community.

Looking at the whole system

Funded by Germany’s International Climate Initiative (IKI) and implemented by the UN Development Programme (UNDP) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the programme (2020-2025) Scaling up Climate Ambition on Land Use and Agriculture through Nationally Determined Contributions and National Adaptation Plans (SCALA) works with 12 countries, including Ethiopia, to identify and support implementation of transformative climate action solutions in land use and agriculture. This entails a set of activities that strengthen the resilience and adaptive capacity of farmer and pastoral communities to climate change, while contributing to agriculture and land use system transformation that address underlying drivers of vulnerability.

Learning about the climate change impacts experienced by farmers is an important part of systems-level assessments undertaken by the SCALA Programme.

This month, a scoping mission comprising a team of experts from FAO and UNDP visited the Harari region to collect information and identify context-specific challenges. Integral were consultations with the federal government, sub-regional government, Sofi Woreda, Kebele Administrative Office and the Lugo Community Group to learn about their specific climate change related concerns and priorities for action.

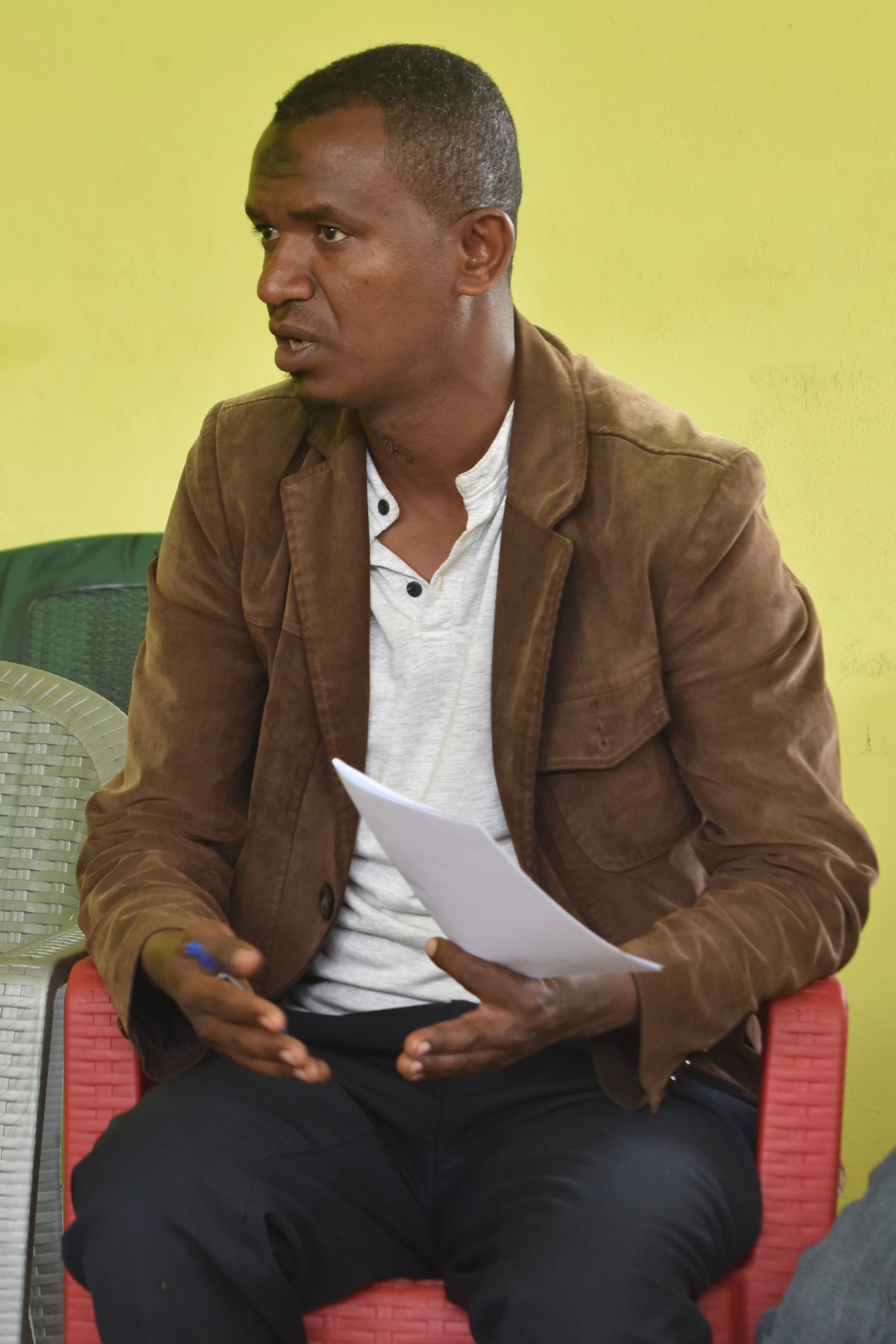

Seid Eshetu, the Climate-Resilient Green Economy Strategy (CRGE) Facilitator from Sofi Woreda/Sub-regional office has witnessed climate change impacting the community, “To curb the climate impacts in our locality, several activities and projects are underway within the community. Natural resource management and water schemes are among the initiatives, with the water scheme having two components: potable water and small-scale irrigation.” The main goal of the 10-year irrigation development plan is to establish at least 1 water point for each farmer.

The initial findings from the scoping activities showed that a community-based integrated watershed management approach can restore degraded lands, while also building the resilience of small-scale agricultural households to climate change and other risks.

The community-based approach includes physical and biological measures to conserve water and soil resources, such as soil bunds and afforestation, contributing to the provision of ecosystem services. Some of the benefits reaped already include the regulation of water flow, flood reduction, protection of the watershed catchment areas and the irrigation canals help bring water from the upper catchment to further down the hills to reach more people and farmlands.

The climate hazards reported here are prolonged dry spells, drought, late and early-onset of the rainy season and flooding, all leading to water stress. Farmers expressed the need for increased access to climate-tolerant crop seeds and varieties, as well as improved on-farm soil management, such as composting, nitrogen-fixing plants, and agroforestry. This information collected will help build evidence to support climate-risk informed local development planning and resource mobilization in agriculture in the assessment area.

***

As well as supporting national adaptation planning, UNDP’s climate work in Ethiopia includes advancing adaptation in the country’s highlands and lowlands, promoting renewable energy access in rural communities, and, under the Climate Promise, raising – and realizing – the country’s climate targets under the global Paris Agreement. Learn more https://www.undp.org/ethiopia

The SCALA Programme Story - Agrifood systems are essential for survival but face growing challenges, particularly from climate change. Vulnerable to extreme weather and shifting conditions, they often lack the support needed for resilience. From 2021-2028, with €26 million in funding from Germany’s International Climate Initiative, the UNDP-FAO SCALA programme collaborates with 23 countries to develop sustainable, climate-adaptive agriculture while unlocking climate finance. SCALA enhances adaptive capacity, promotes nature-based solutions, and supports national climate goals, delivering mitigation co-benefits.

Locations

Locations