The Promise of Experimentation in Development: What Works and What Doesn't

October 16, 2023

In Guinea Bissau, an experiment on access to justice has shown the benefits of implementing mobile justice units and bringing registration services directly to hard-to-reach areas.

Development policies that do not work

“We live in a world of worry.” This is how the UNDP Human Development Report (HDR) 2022 describes the impact of the intersecting global crises today. The Human Development Index, which measures a nation’s health, education and standard of living – has declined for two years in a row now. The report highlights growing complexities exacerbated by increasing planetary pressures and inequalities. Much of the progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals has been reversed.

In this race against time, policymakers need actionable intelligence to tackle new and shifting problems as well as tools to react, learn and correct the trajectory of public interventions in a more agile manner. How can they test whether policies are working and adapt to improve existing programs? How can policy makers embrace an experimental approach where assumptions are tested systematically before the implementation stage?

This is where we come in. The UNDP Global Accelerator Lab Network is designed to close the gap between the current practices of international development and the pace of change. One of the ways we do this is through experimentation which is about systematically testing new hypotheses, policies and novel interventions to inform early on decision-makers in national and local governments across 115 countries. We have been rolling out hundreds of small-scale, budget-friendly and fast experiments to help policymakers learn with us what development policies do not work in their context.

Experimentation helped us and our partners learn, for instance, what are the multiplier effects of accessing free Internet in public spaces in El Salvador, what would be the most effective way to manage waste in cities like Tbilisi and Addis Ababa, or what type of digital platforms would offer the greatest citizen engagement when creating public policymaking processes in Paraguay.

This blog aims to present what we, Heads of Experimentation, have learned on the ground in such diverse contexts from Guatemala to Fiji to Zambia. We also reflect on the role experimentation plays in accelerating SDG progress and scaling solutions.

Waster pickers collecting recyclables at Chunga dumpsite in Zambia.

The proof is in the pudding: the case of waste management

As we look for patterns across our Network, we identified that 20 Labs have recently conducted experiments to address the issues of waste management and opportunities of circularity with a range of interventions, such as using behavioral nudges for in-house recycling in Georgia and turning plastic waste into commercial opportunities in Nepal.

Prototypes and proof of concepts are being used by the Labs as novel ways of monitoring waste to then provide policy makers with new insights on ways to increase recycling rates in urban areas and address improper waste management. The UNDP Tanzania Accelerator Lab tested whether satellite data could be used to monitor and quantify waste in the city of Mwanza. Guatemala investigated if publicly available satellite images can help to identify the location of clandestine waste sites. In the Philippines, satellite data is being explored for better decision-making. All three prototypes show not only an accessible and cheaper way of monitoring waste, but also reveal the existence of new sites that were previously not registered and thus off the radar of government services.

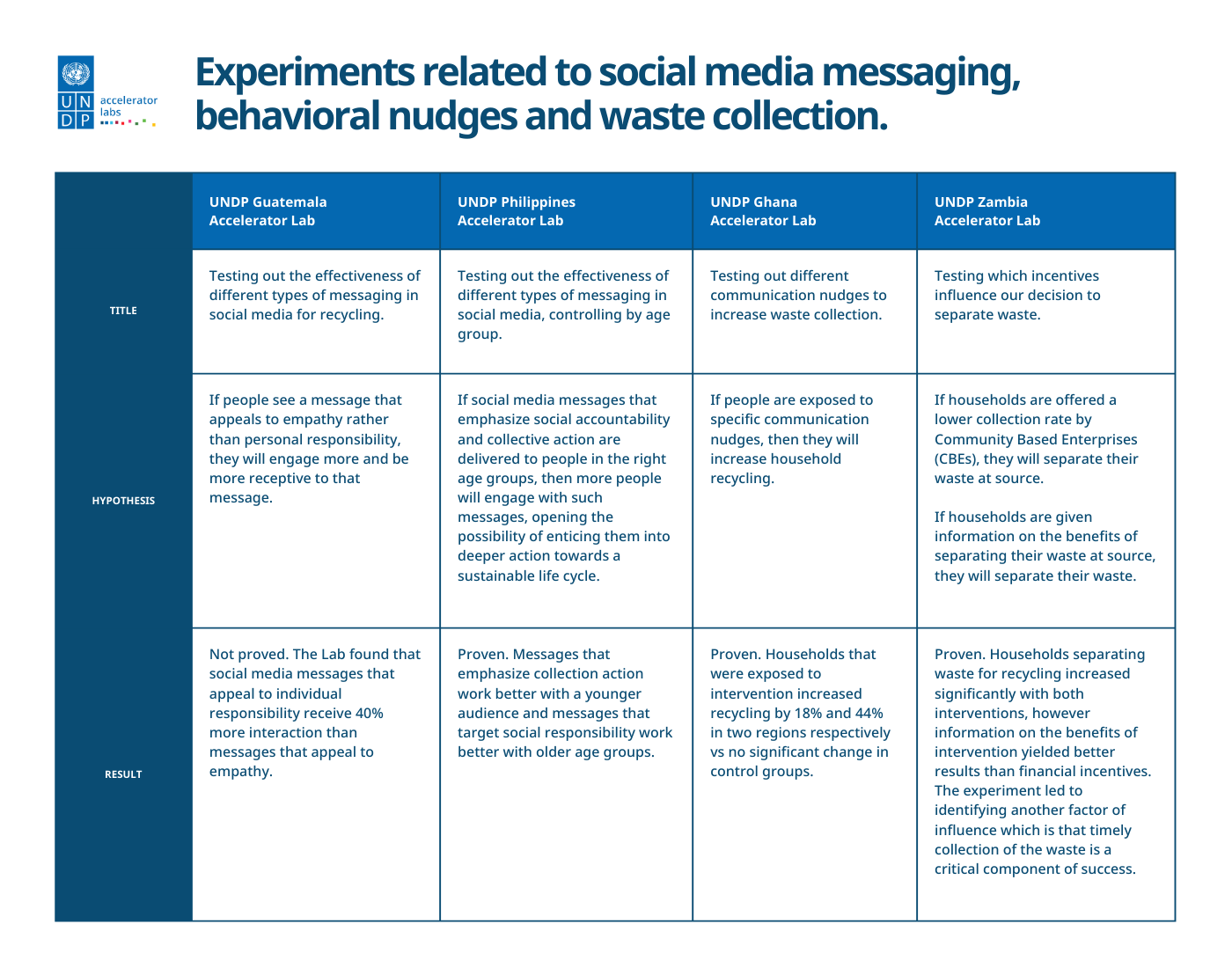

Another approach to experimentation in the waste management space is the use of social media messaging to influence waste collection and recycling. (See chart below). These experiments have the potential to go beyond their controlled environment. In Ghana, an experiment testing the impact of strategic communication on waste collection demonstrated that such interventions could boost household recycling. These insights have informed discussions on recycling by the Ghana National Plastic Action Partnership.

This table summarizes some of the experiments conducted in the network on waste management and communications. Experiments allow us to learn what works and what doesn’t in a fast and open way.

Using experiments to find out not only what works, but also to explore new ideas

Prototyping and proof of concepts help us understand and address problems early on. By creating a safe, controlled environment where new ideas can be trialed, prototyping allows us to explore the viability of policies and interventions. Our fast and agile way to test on-the-ground programs is a de-risking mechanism for policy makers, who can then take our learning to scale, as shared in the Ghanaian example above.

We create a space to fail, which does not just benefit decision-makers but also allows us to engage the private sector, academia and civil society in development-related issues. For example, in the past three years, the Accelerator Labs have partnered with more than 1,500 organizations, the majority of which have participated in these prototypes and experiments. Experimenting fast safeguards public resources and trust, and ensures that when a policy is rolled out, its effectiveness and efficiency have been tested and proven.

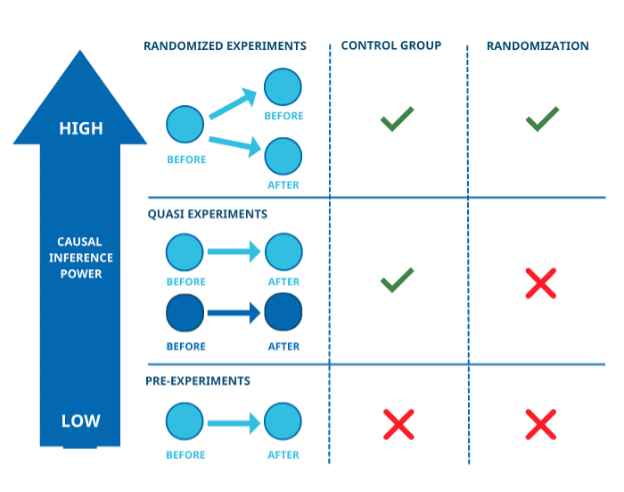

Figure 1 Causal inference power vs type of experiments.

Lessons in scaling — an experiment in itself

As they say, “if a tree falls in the forest and no one hears it, does it make a sound?” In the same way, if an experiment in the world of sustainable development is kept contained, it does not serve its purpose. In general, scaling is difficult due to a variety of reasons, and we are learning that there are barriers to adopting the results coming from experimentation, especially in the public sector, which is more risk adverse. When moving from experimentation to scaling, these are some concepts that serve as reminders that we must consider:

- A successful experiment is one that we can learn from. To scale outcomes of an experiment, one needs to identify, document and share out clear learnings from the experiment. This is what we aim to achieve by blogging (working “out loud”) and sharing our learning along the way.

- Fall in love with the problem instead of the solution. We should allow for the iteration of multiple ways to solve complex problems. In Guinea Bissau, an experiment on access to justice has shown the benefits of implementing mobile justice units and the government is now scaling the solution nationally. However the Lab continues with its portfolio approach on other experiments in the justice sector, such as experimenting with e-portals which will make judicial records available digitally.

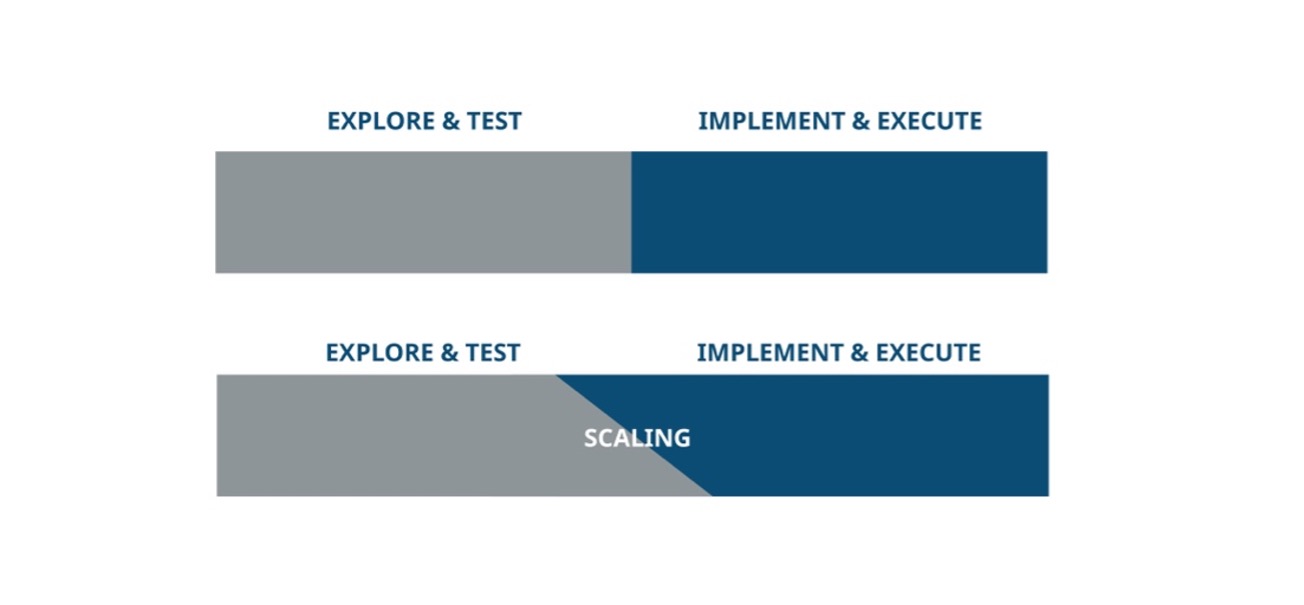

- Implementing the solution at scale is an experiment in itself. Scaling a tested solution to improve the living conditions of a broader population is not just a mere replication of results; it's an exploratory process in its own right. We call this process intermediate scaling, and it involves not only expanding the solution but also adapting it to various contexts. It's a transitionary phase where the focus is not just on growing in size but also on testing how the system adapts and responds to the challenges of full-scale implementation.

- Engaging multiple actors from the get-go is essential, especially government stakeholders at different levels of seniority and risk appetite. This will strengthen their sense of ownership at a later stage and increase the adoption of the experiment and therefore its scaling potential.

Figure 2: From experiment to scale in development: an intermediate transition is essential.

An ongoing journey

Our exploration in the development landscape, boosted by a culture of testing and learning, has opened new avenues to address complex challenges and the UNDP Accelerator Lab Network stands as testament to the transformative power of experimentation for sustainable development.

Yet, there is much more ground to cover. In the spirit of experimentation, we are also learning as a Network as we go, and we are enhancing our ability to capture and share greater insights from our experiments, as well as to improve our ability to scale and boost the diffusion of public domain experiments globally.

If your organization believes that you can contribute to our collective effort to embed experimentation in the development world, please share your thoughts and ideas with our team.

Contributors:

Ayad Babaa, Head of Experimentation, UNDP Libya (2019-2023)

Javier Brolo, Head of Experimentation, UNDP Guatemala

Eduardo Gustale, Monitoring, Experimentation and Learning Specialist, UNDP Accelerator Lab Network

Zainab Kakal, Head of Experimentation, UNDP Fiji (2019-2022)

Isa Lopes da Costa, Head of Experimentation, UNDP Guinea Bissau (2020-2023)

Nampaka Nkumbula, Head of Experimentation, UNDP Zambia (2019-2023)

Prachi Paliwal, Partnerships Analyst, UNDP Accelerator Lab Network

Lazar Pop Ivanov, Head of Experimentation, UNDP North Macedonia Accelerator Lab

Locations

Locations