Reform of the System for Balša's Happier Childhood

May 3, 2022

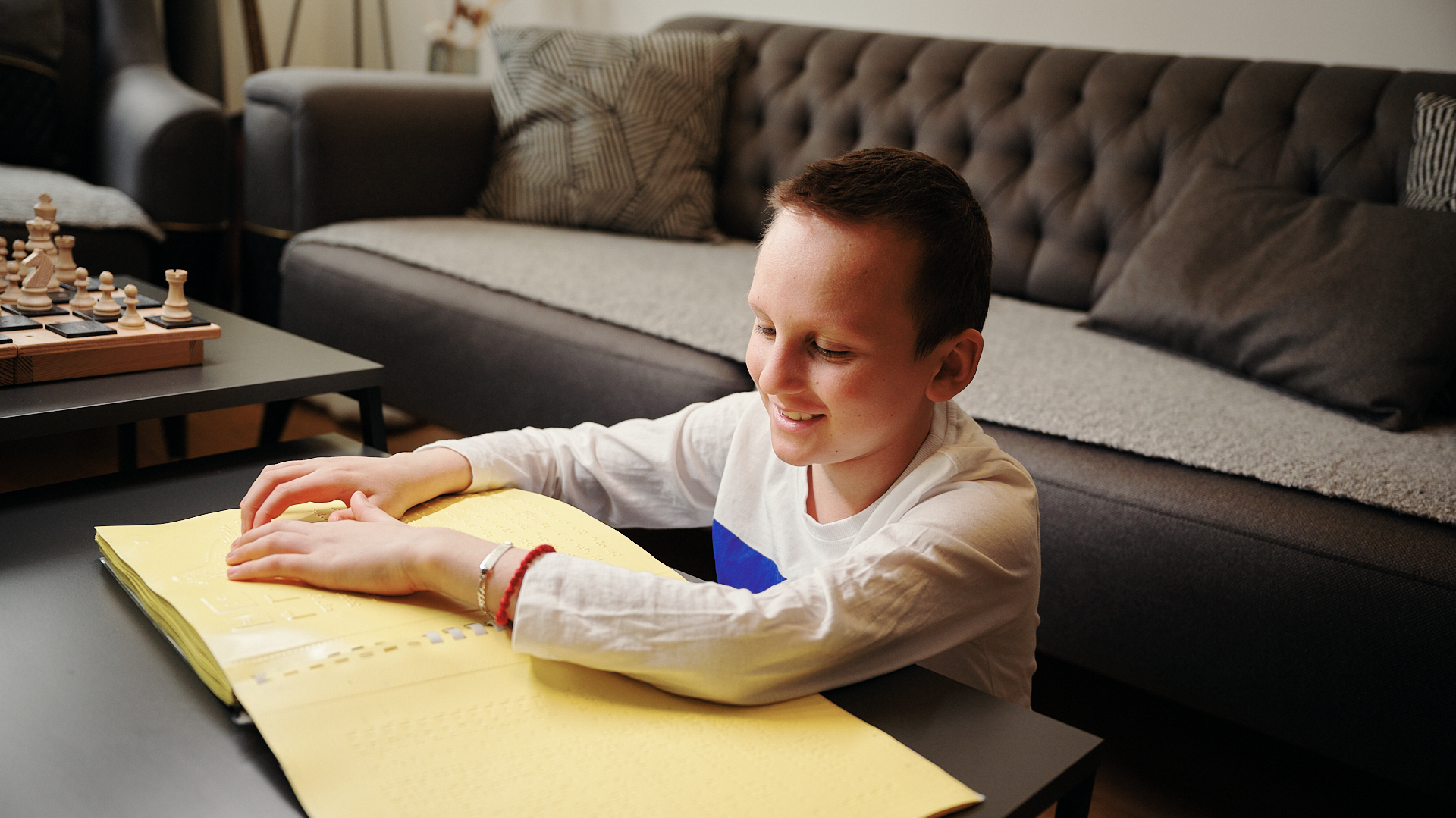

Ten-year-old Balša Marljukić learns Braille, rides a scooter and plays chess with a warm, broad smile.

"When I grow up, I would like to be a chess teacher and teach other children to play it, just like I am being taught. I wouldn't mind teaching those who can't see, like me, to play chess" Balša says.

Due to a severe illness, Balša completely lost his vision at the age of five.

Hospitals, counters and paperwork have become an inevitable part of his life since then. As he makes moves on the chessboard and thinks carefully how to win, he and his mother Dragana Joksović fight battles to enable Balša to exercise his rights.

According to the last census, as many as 11% of Montenegrin citizens have difficulties while performing daily activities due to a long-term illness, disability or old age. While trying to exercise their rights, they face numerous barriers - complicated procedures, lack of information, but also society's prejudices.

"No one has ever instructed us or helped us, or at least said: 'Do it this way, it is easier for you, bring that paper, you can do that here.' I had to go from one counter to another and plead with someone to explain things to me," Dragana says.

That is why she has often felt as if the system was not there for their sake, but vice versa, she explains.

Persons with disabilities exercise most of their rights based on the findings and opinions of various disability assessment commissions. There are more than 30 such commissions in Montenegro. The criteria based on which they make decisions differ and are often not uniform. For example, in order to exercise just one of their rights, a person often has to show up before the same commission multiple times.

"I had to go and show up before the commissions several times for the same thing, and no one would pay attention to us. Eventually, they would just have a look at him and say that he is rejected or that they would let us know. Then, I took Balša once and told him at the entrance: "Come on, go to that lady alone now". Of course, he couldn't do it, and only then they turned their attention to us, took a closer look at the documentation and finally approved our personal disability allowance", Dragana says.

Balša doesn't like waiting and doesn't like commissions either. He loves cartoons, summer and the sea. But most of all, he loves to play with his sister and friends on the Sutomore beach, to check pebbles and shells with his small fingers, which made the days of fighting the disease easier to get through.

People with disabilities are often insufficiently informed about their rights and depend on the will and assessment of the administration staff. The commission's assessment sent Balša to the Resource Centre "June 1st”, and not to a regular primary school.

"The moment she met Balša, teacher Jadranka said that he did not belong to the Resource Centre, that their school's curriculum was not adapted to his abilities. She told us that Balša should go back to regular, inclusion-based schooling. I was not even aware that there was such option until that moment," Dragana said.

He could not exercise immediately his right to a teaching assistant either, but the teacher and Balša's friends did their best to make staying at school and mastering the lessons as easy as possible for him.

"Return to regular school was great. The teacher did her best to inspire students to accept him so that Balša does not feel different from other children," Dragana said.

The fight for Balša's health and life without barriers would be easier for his mother if the information were provided and procedures completed in one place. This will be possible through the reform of the disability assessment system - a project that UNDP is implementing with the Government and civil society organizations, with the financial support of the European Union.

Disability and needs of all peple with disabilities will be assessed in one place. The assessments will be made based on the human rights model, and not on the medical one only, as it has been the case so far. This means that the barriers they face will also be assessed, as well as the support required to overcome them and enable people with disabilities to lead an independent life. This will significantly simplify procedures for them to exercise their rights and make the system more accessible.

And while he waits for the system to be improved, procedures to be simplified and to exercise his rights just like his peers, Balša looks forward to going back to school and seeing his friends, riding a scooter and perfecting his chess skills - because it is not easy to become a grandmaster!

Locations

Locations