To what extend does training and practice of participatory governance increase trust in local governments?

Learning Through Play: Evaluating the Impact of Tavarandu - Part II

21 de Diciembre de 2023

If you are interested in Part I, you’ll find it here.

Read the Spanish version here

Also collaborated: Mateo Servent (1).

Tavarandu is a participatory governance program that promotes capacity building for citizen participation in local governments and communities. While our passion for citizen engagement is all we need to invest in these initiatives, we also want to test new methods and tools and learn about their impacts. In particular, we know that there is an interdependent relationship between citizens' trust in their institutions and participation, and the greater that trust, the greater the quality of democracy. And care for our democracies is another reason we invest in participation. Our hypothesis is simple: if municipal officials, trained in participatory governance, facilitate citizen engagement activities in their communities, then citizens' trust in institutions will increase, and with this, democracy and the possibility of development and welfare.

But how do we measure that trust? Do we ask each citizen how much they trust their local government? It is an option, and we have done it in the past to measure trust and social capital, but there is a much more fun way to do it: by playing!

The Public Goods Game: measuring the perception of trust in local government

The fun way comes from the world of game theory. Through a Public Goods Game, we seek to simulate a real scenario in which participating people must make decisions that reflect their levels of trust and valuation of public goods. Thus, we can collect the information we need to measure whether training in participatory methods for municipal officials and their application, by the same municipal official, with groups of adolescents, increases, or not, confidence in municipal planning processes and their local government. Our local version of the public goods game is built with banknotes from a local version of the traditional game Monopoly.

In the relationship between citizens and government, trust plays a crucial role in the way people interact and perceive government actions. Research has found that social norms (the relevance given to reciprocity and altruism), group affiliations, and past interactions influence individual decisions and perceptions, and the formation and maintenance of trust.

In our intervention, we measured trust through the money that participating people would be willing to invest in public goods that are managed by the municipality. We adapted an investment game used in economic studies with scenarios where citizens "invest" their trust in actions such as paying taxes or contributing time for common goods, evaluating how the characteristics of the environment and government policies affect trust. The trust in public goods game helped us study how individuals make decisions in situations where cooperation can benefit the collective, but also presents a dilemma for the individual between acting selfishly, prioritizing their individual interest; or in a cooperative way, assuming a greater individual risk for a greater collective well-being.

According to several studies trust is supported by motivations and underlying factors, such as the perception of reciprocity, the history of previous interactions, and the perception of justice. People are more likely to trust if they perceive the same intention in their counterparts, if on previous occasions they have already acted in a similar way and were satisfied, and if the cause in which they place their trust seems valuable to them. These drivers of trust are in turn influenced by cultural, historical, and personal aspects.

What Was the Game About?

It was a role play. The volunteers in charge of implementing the game presented themselves as representatives of the local government. They explained that the Municipality of Natalio is developing its Municipal Sustainable Development Plan in a participatory manner and launched a modality to allow all citizens to contribute with ideas and financial contributions for the construction of works of common good and that after a series of participatory workshops had defined the main investments to be made.

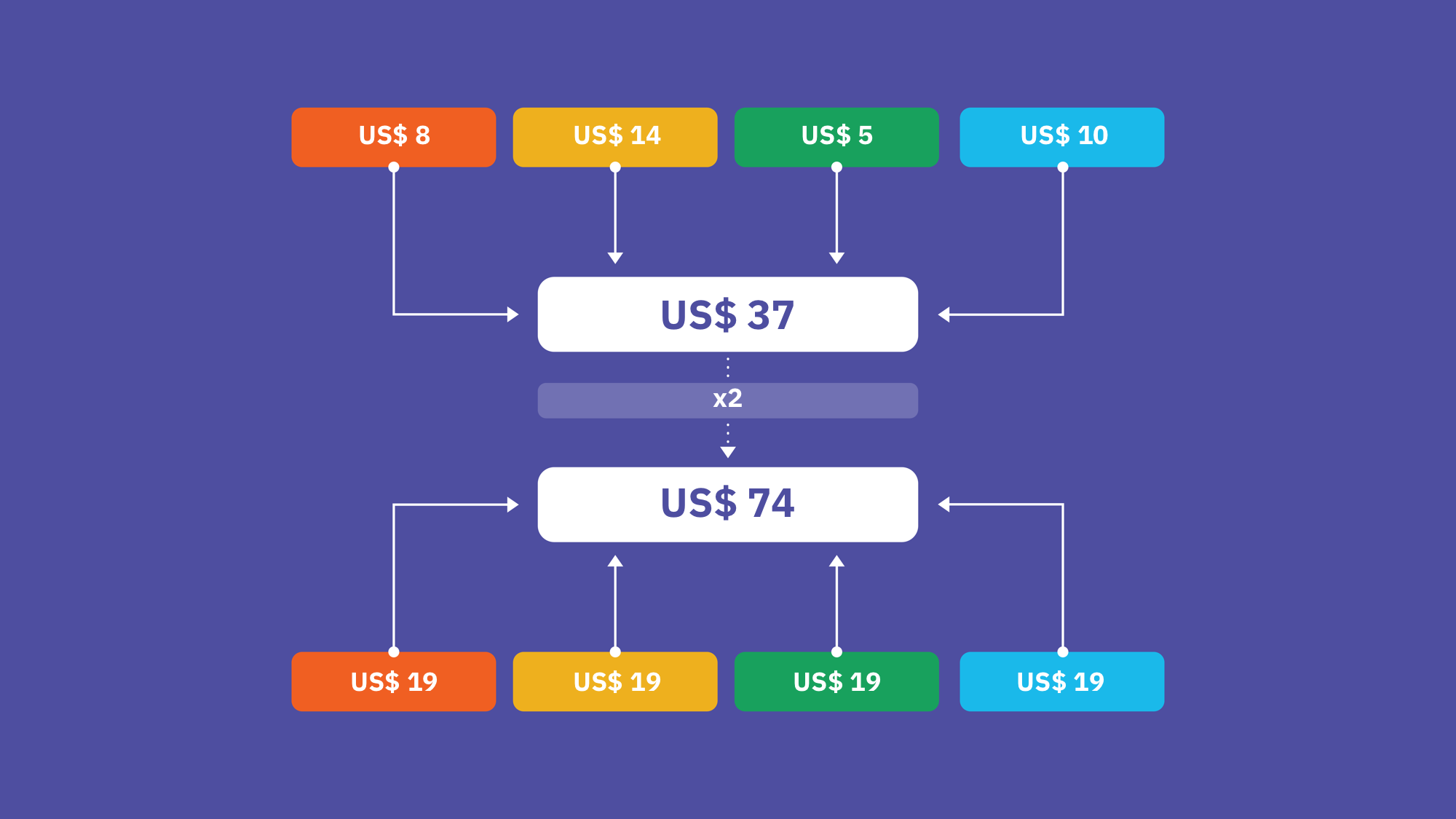

The participating students assumed the role of citizens in the game who were invited to invest their money in social and infrastructure works for the city. For this simulation, they received the equivalent of 100,000 guaraníes (about $14) in game banknotes. Each participant could decide how much to invest. The money would be part of a common fund that the Municipality would invest in projects of the Municipal Development Plan selected by citizens (squares, docks, schools, public transportation and drinking water system). Participants were promised that at the end of ten years the investment would be doubled, and the benefits would be shared equally among all participants, regardless of how much money they had contributed (Graph 1).

Graph 1. Investment and return scheme example, according to the rules of the game

Participants could deliberate among themselves to define how much it was convenient for them to invest, but each one's decision was individual and anonymous. Each participant placed his or her contribution in an envelope, the total was tallied, and the construction of the development works was simulated, according to the total amount collected.

Participants toured a photo gallery to enjoy the public goods built with their contributions. The passage of ten years was simulated, the amount of the common pot was doubled, and the division of the contribution in the envelope where they originally contributed was returned to the participants equally. To measure both the impact and the difference between participants who had or had not participated in the training day, participants were asked to respond:

How much did you invest?

How much did you receive back?

Are you satisfied with the result of your investment?

If you did it again, would you invest a larger, the same or smaller amount?

The dynamic closed with a plenary discussion with the participants, key messages about public goods and the importance of trust, citizen participation and cooperation. The details of the Civic Day in which we applied the game, facilitated by municipal officials, can be read in this first blog.

What did we learn?

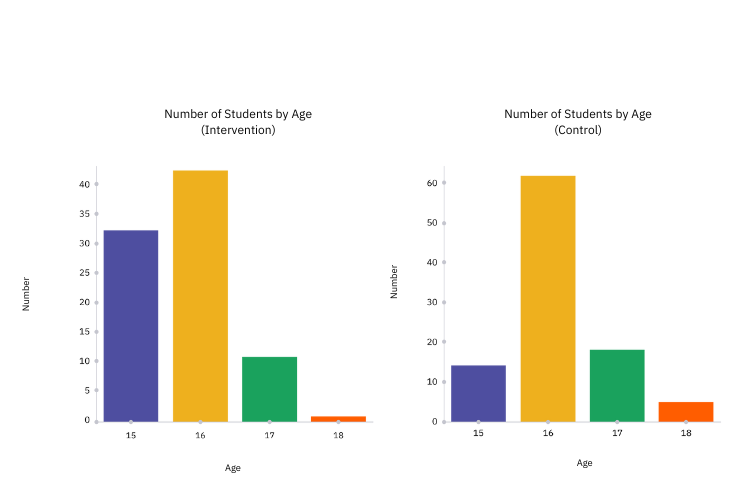

The activity took place between October 24 and 26 in the Natalio district, in the Northeast of Itapúa department. We collected information from 12 classrooms, with 178 participants (65 in the intervention group, 112 in the control group), all from first and second grades of four secondary schools in the city. In addition, two students from the Educational Sciences Program at the branch of the National University of Itapúa participated as volunteers, as well as one Argentinian student from the Master's Degree in Political Science at CIDE (México), who volunteered to help us analyze the resulting data.

Does training in citizen participation tools increase confidence towards investment in public goods planned by local government? In this experience, certainly it does.

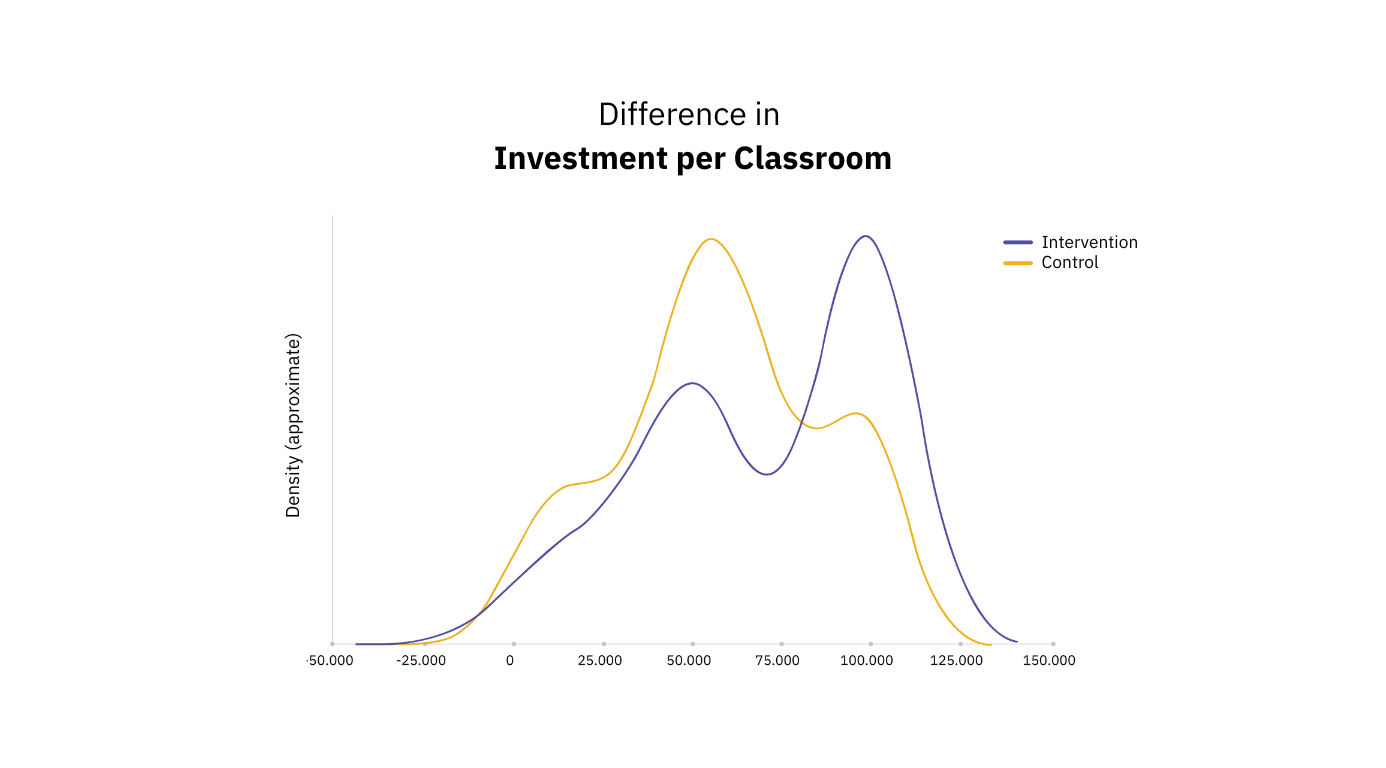

We found a significant difference in favor of the intervention of Tavarandu. Students who participated in the Civic Day facilitated by municipal officials invested more, on average, than those who did not participate. The intervention managed to increase investment by around +19%. The average investment in the control group was 59,598 guaraníes (around $8), and in the intervention group it was 70,692 guaraníes (around $9,5), as seen in Graph 2. The effect size, that is, the size of the difference between the two groups, was relatively small (0.436, but statistically significant). It should be considered that the intervention only consisted of one day of training; and its effect could possibly have increased with greater intensity and more days of training and participation. On the other hand, the average amount in both groups was above 50% of what was available for them to invest, which may be a signal that in fact, both groups had already high levels of trust before the intervention.

Graphic 3. Investments by Class

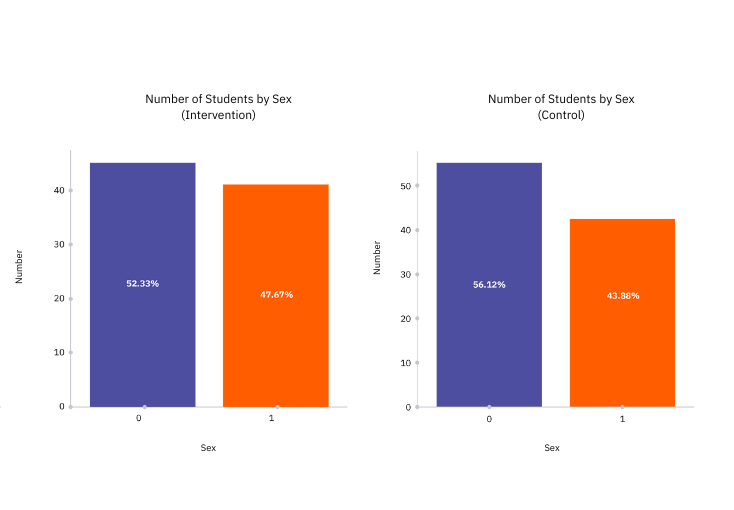

We identified a difference in the distribution of ages and sex in the randomized intervention and control groups, as seen in graphs 2 and 3. The intervention participants were on average younger and in both groups, there was a higher proportion of women.

Promotion of citizen participation

According to the evidence collected by the participants, the training space in citizen participation methods allowed more adolescents to participate in spaces to which they are not usually invited. For example, because of the planning of the Citizen Laboratory, a community call was organized to renovate Los Pioneros square, in Natalio.

Of the 42 people who participated in the call, 40% were students and teachers who had participated in the previous Tavarandu activities, and joined when they heard the invitation to expand their participation in civic activities. This has enormous implications for public policy: involving adolescents in citizen participation processes, such as the one we experienced, perhaps has the potential to also increase their levels of participation in subsequent processes, such as electoral processes. Can we think about a citizen laboratory program for teenagers 1 or 2 years before they are legally qualified to participate in elections? In the last general elections in April 2023, the participation of young people aged 18 to 24 was 55%, below the 61% of the general population. Considering that youth participation is one of the main current electoral challenges, the application of innovative civic education strategies sounds like an interesting bet.

Our small intervention to build trust in public goods administration allowed us to identify the potential that the training space in civic technologies and methodologies must increase trust, and through this, the quality of democracy.

If such a short but intense process achieved these favorable results, an integrated policy for promoting participation in schools, colleges and communities has the potential to increase the levels of citizen participation and the quality of democracy. Through play and game theory, we now have interesting clues about this.

To learn more about the Hechakuaa Citizen Laboratory, we invite you to download the toolkit that we developed after its first edition.

To learn more about the entire Tavarandu program, we share the following links:

(1) Mateo Servent collaborated with the experiment. At the beggining, he developed a Python code to randomize the courses and later contributed to the analysis of the results obtained. He also contributed to the writing of this Blogpost. Servent is a full-time student in the Master's Degree in Political Science at CIDE (México City). Throughout his career he has carried out academic stays at the Freie Universität Berlin, Universidad de San Andrés and Universidad de Guadalajara. In addition, he was a research assistant for projects at CONICET, the National University of Cordoba and the 1 + D + i Agency in Argentina.

Locations

Locations