To what extend does training and practice of participatory governance increase trust in local governments?

Learning through play: how we evaluate the impact of Tavarandu - Part I

14 de Noviembre de 2023

Read the Spanish version here

If you are interested in Part II, you’ll find it here.

Also collaborated: Mateo Servent (1).

We had already concluded the talk, collected the surveys, and stored all the materials we used during the activity. We were a gang of four facilitators and had just completed our tasks after visiting the last first-year classroom in the district of Natalio, a city located within the region of Itapúa. We were ready to say goodbye. However, as we looked into the eyes of a curious teenager, it became evident that something more was needed. We decided to improvise a closing round, asking each of the twenty students to express in one word the feeling they were left with. The word that resounded the most was 'curiosity.' It was a gratifying moment, as it seemed we had succeeded. If we had managed to plant the seed of curiosity in those young minds, it was all worthwhile. Curiosity is what fuels science and innovation, opening doors to new possibilities, encouraging exploration, and inspiring change in the world.

Between October 23 and 26, our UNDP Acceleration Lab Team conducted fieldwork to assess the impact of the second edition of the Tavarandu (1) Participatory Governance Program. During this period, we initiated the Hechakuaa (2= Citizen Laboratory, which began with a training phase for Municipality of Natalio officials on citizen participation concepts and tools. Subsequently, we organized two participation events—one open to the general public and another tailored specifically for adolescents, a demographic often overlooked in participation processes. Using methods involving play, meaningful conversations and theater, we learned about citizen participation and put it into practice to generate proposals that would improve the city's public spaces.

To assess the impact of these activities on the group of adolescents, we applied game theory and employed a version of the public goods game. Our objective was to gather evidence on how training municipal officials in citizen participation tools can foster trust among citizens and enhance their engagement in local initiatives.

Why is it crucial to enhance citizen participation, especially in traditionally excluded groups?

Citizen participation is the cornerstone of an open and democratic society. The civic spaces and processes that enable this participation allow citizens from all sectors of society to engage directly in the resolution of political, economic, and social challenges. This, in turn, fosters higher levels of trust between people and institutions and generates ownership over decisions and actions over shared resources. Improving trust between citizens and institutions is essential for preventing the deterioration of democratic processes.

Since the Convention on the Rights of the Child, states have recognized the right of children and adolescents to express their opinions and be heard, a recognition reflected in their constitutions and laws. In Paraguay, the Children and Adolescents Code ensures, among other things, 'the right to organize and participate in student entities' and the right to an education that 'prepares them for the exercise of citizenship.' However, historically, these groups have been excluded from instances of participation that could indeed prepare them the exercise of becoming active citizens, fully engaged in the development of their communities.

Tavarandu, a capacity-building program for innovation and participatory governance, tackles this challenge by co-designing training, promotion, and facilitation programs for citizen participation that are tailored to local-level processes. This year, it introduced a special component aimed at engaging adolescents, allowing them to be part of a local citizen participation process and learn through the exercise of their right to participate.

Our hypotheses

Our goal is to assess how training municipal officials on methodologies and tools for citizen participation has an effect on the quality, diversity, and scope of citizen participation in local planning processes.

Our experiment is based on two primary hypotheses:

If we provide training to municipal officials, then their perceptions and opinions regarding the application of participatory tools in municipal processes will improve.

If trained municipal officials facilitate citizen participation activities in their communities, then the quality, diversity, and scope of citizen participation in local planning processes will increase.

The Experimental Program: A step-by-step overview

During the initial phase, the program provided training to municipal officials in Natalio on participatory methodologies, public innovation, and the use of civic technologies for the creation of Municipal Development Plans. The training was conducted by a team of consultants from Mentu, spanning two days of intensive instruction, complemented by virtual tutoring sessions and occasional in-person support.

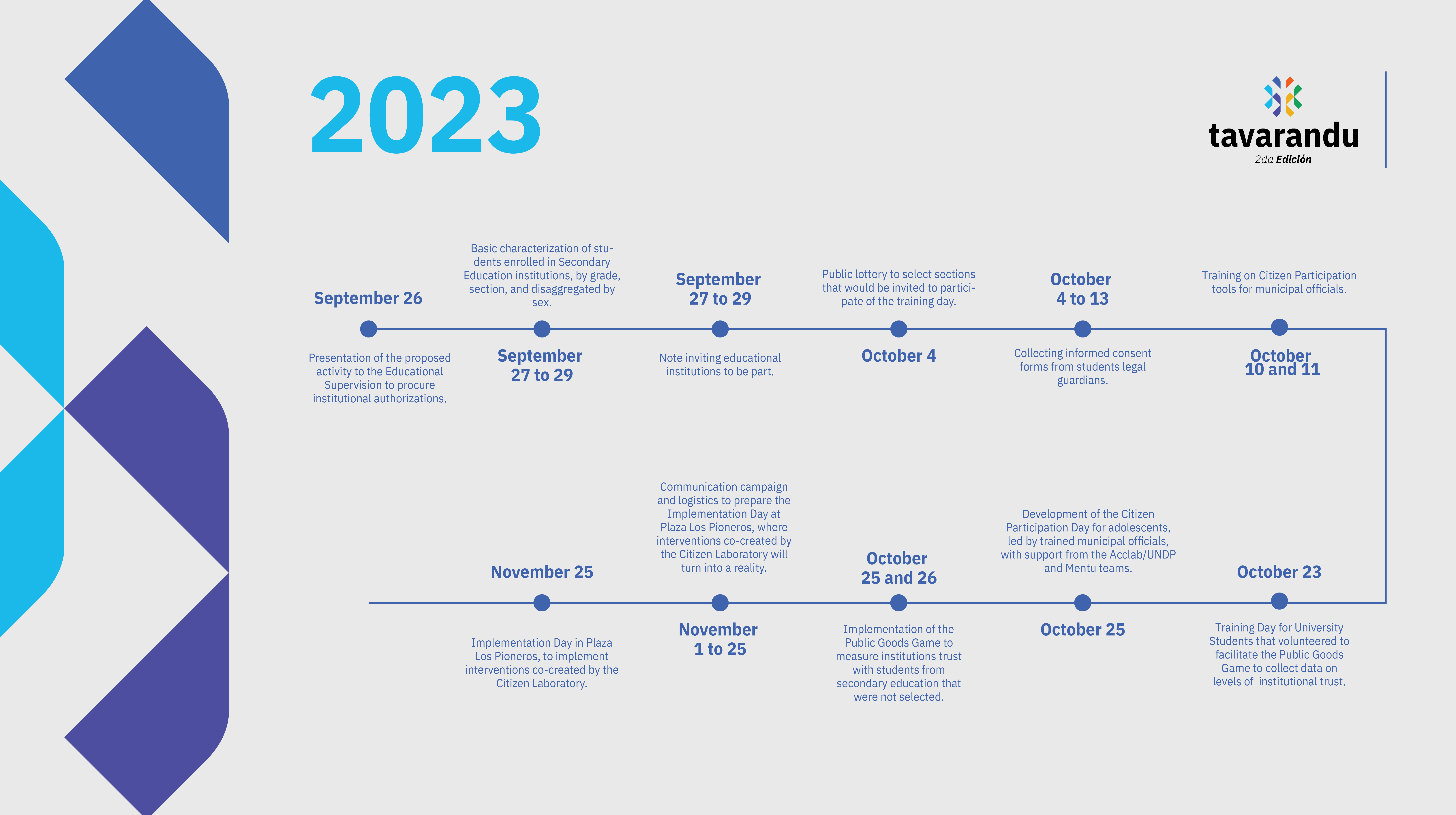

Graph 1. The roadmap of the Tavarandu edition in Natalio

During the second phase, we organized the Hechakuaa3 Citizen Laboratory, consisting of a series of participatory activities led by previously trained municipal officials. The primary goal of these activities was to co-create urban interventions that would improve public spaces in the city center of Natalio. One of these activities was targeted to a group of citizens who are not commonly included in participatory processes: adolescents aged 15 to 17 who attend schools within the municipality.

To provide hands-on training in citizen participation, we developed a special program for teenagers which allows them to learn about participation and at the same time add their voices to the Hechackuaa co-creation process, in which Natalio's citizenship received their proposals as input to work on them during two participatory workshops.

The Citizen Laboratory aimed at adolescents was arranged as a randomized controlled trial, wherein we randomly selected participating secondary school classes. We then measured levels of institutional trust in local government among both the participating and non-participating classes using a confidence game and a characterization survey. The selection of participants was conducted through a public lottery, overseen by the directors of the invited public schools.

The participating classes were randomly assigned into blocks based on administrative data provided by the local Educational Supervision, which helped to characterize each class. Subsequently, we issued informative notices and requested the signature of informed consent forms from the parents, guardians, or legal representatives of each participating student in both groups.

The Citizen Participation Training Program for adolescents

A total of 65 first and second grade students from the Domingo Robledo, Ricardo Musch, Puerto Triunfo and Natalio Km 23 schools participated of the main activity. The training's objective was to enhance the confidence in municipal planning processes for the generation of public goods in a group of adolescents, through participatory governance strategies and methodologies applied by trained officials.

We initiated the program by using theatre skills to introduce a simplified version of a frequently used concept known as the Ladder of Citizen Participation. The adolescents were organized into groups and assigned the task of representing different role models of leadership, each displaying practices that go in line with the different levels of participation in the ladder, including manipulated participation, decorative or symbolic participation, informed participation, consultative participation, collaborative participation, and creative participation for co-creation.

We saved the highest level of the participation ladder, co-creation, for the hands-on moment. Using the 'Pro-action Coffee' technique, the group of adolescents collaboratively expressed and developed their ideas on how to improve public spaces in Natalio. At the end of the process, each group presented their proposals as if they were 'News from the Future,' envisioning the front page of a hypothetical future newspaper where their ideas had become a reality.

By the end of the activity, we used an adaptation of a Public Goods Game as a strategy to measure levels of trust while also introducing and explaining the concept of public goods. After finishing the game, we invited those in attendance to join the upcoming activities that the municipality would be organizing.

In our next Blogpost, we will share our findings about the impact of this small program on levels of trust and perceptions about the value of public goods. Stay tuned to our networks!

To learn more about the Hechakuaa Citizen Laboratory, we invite you to download the toolkit that we developed after its first edition.

To learn more about the entire Tavarandu program, we share the following links:

(1) Mateo Servent collaborated with the experiment. At the beggining, he developed a Python code to randomize the courses and later contributed to the analysis of the results obtained. He also contributed to the writing of this Blogpost. Servent is a full-time student in the Master's Degree in Political Science at CIDE (México City). Throughout his career he has carried out academic stays at the Freie Universität Berlin, Universidad de San Andrés and Universidad de Guadalajara. In addition, he was a research assistant for projects at CONICET, the National University of Cordoba and the 1 + D + i Agency in Argentina.

(2) Word in Guaraní that comes from "Tava", people and "Arandu", wisdom, and we can translate as “citizen knowledge” or “collective intelligence”.

(3) Word in Guaraní that we can translate as “knowing how to look.”

Locations

Locations