--- Image caption ---

What is the purpose of building a network of mini-Labs of volunteers?

Complex development challenges, such as resilience to climate change, early recovery from emergencies, social inclusion, poverty reduction, among others, are difficult to solve, because conditions change rapidly and have multiple interrelated causes. Volunteer organizations are an unusual actor with great potential for contributing to the solution of these complex development challenges, as they can help to understand what works in the context where development needs emerge.

Through their hands-on activities, volunteer organizations are some of the first to discover not only what are the emerging development needs people have, but also the innovative ways in which people try to overcome these needs. Even though there is little systematic data about the contribution that volunteer organizations make, they are engaged in a wide variety of activities, throughout most of the territory, implementing a diversity of approaches, constantly renewing themselves and trying out new things.

Moreover, the types of contributions that volunteer organizations make are the kind that can be particularly amplified by incorporating some of the methodologies used by the UNDP Accelerator Labs’ learning cycle. These organizations are a potential ally to UNDP’s efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, as their “eyes and hands” bring in broader perspectives from people in multiple locations. For example, by aggregating the experiences from volunteers there is great potential to generate collective intelligence about what is needed, what is being done, and what we are learning about how to achieve sustainable development.

Therefore, we ventured into experimenting on how to build a network of mini-labs of volunteer organizations to accelerate sustainable development. We have started by conducting a series of workshops to train volunteer organizations on the implementation of methodologies from the learning cycles. Through this initial step, we aimed to empower the contributions of volunteer organizations and prepare their involvement in future activities with UNDP.

How did the idea originate?

As with many ideas, the behind-the-scenes process that led to its implementation includes some serendipity and many conversations. In this case, during an initial informal exchange in February 2021, the coordinator of the United Nations Volunteer program in Guatemala shared with us some ways in which volunteers help to achieve development goals. She then introduced us to the Centre for Guatemalan Volunteering (Centro de Voluntariado Guatemalteco, CVG), a “hub organization” that promotes activities for volunteers to get involved or to advance their personal development.

For Guatemala’s UNDP Accelerator Lab, the great potential for collaboration was evident after meeting CVG. They had the capacity to contact a large number of volunteer organizations from different sectors, including government, private enterprises, religious, civil society and local communities, working on different development challenges throughout the country. Harnessing this potential reach in the implementation of learning cycles would enrich the portfolio of solutions and information sources that can be identified and tested. Also, CVG offered stability for investing in a long-term partnership, even if individual volunteers themselves rotate.

On the other side, CVG also saw great potential in the new methodologies that the Accelerator Lab could offer to increase the impact that volunteers have on development. CVG understands that volunteers are driven in part by their intention to enact their personal commitments, have a positive impact in their communities, grow with new experiences, and meet other supporters of their values. As a response, CVG engages volunteers by offering a yearly series of training workshops. Precisely, the new methodologies brought by the Accelerator Lab were considered a great fit for this year’s sessions.

Hence, the idea of building a network of mini-labs of volunteers was born from the recognition of mutual benefits between the Accelerator Lab and CVG, as well as coincidence and good timing. This way, we were able to move forward with the idea building from an existing capacity of the Accelerator Lab -knowledge of new methodologies- and an existing space for sharing them created by CVG -annual training sessions.

How were the training sessions implemented?

The very first step to enable collaboration between the Accelerator Lab and CVG was to formulate a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU). Some things that helped its agile elaboration was to gain initial support from the Country Office’s Resident Representative for validating the idea; clarifying the involvement required by UNDP, as well as the potential risks and benefits of the expected results. Building from the template, we made special efforts to be as clear and specific as possible. It also helped, that there were no financial resources needed from UNDP.

It is also important to mention that all along the Accelerator Lab greatly benefited from the involvement of a United Nations Volunteer who is serving as an Experimentation Assistant. In particular, she has brought in substantive skills from her anthropology background, helping to identify and bridge epistemological paradigms when adapting the workshops contents. Also, her dedicated support in developing the materials, conducting the workshops, and managing the relation with counterparts was key to increase the capacity needed for a successful implementation.

Then there was the call for participants, which was led by CVG. The art used was relatively simple, and diffusion relied mostly on direct messages. The target audience were leaders from volunteer organizations subscribed to CVG’s messages. Although the workshops did not exclude other organizations, this was a pilot project intended for a more manageable group. Nevertheless, the starting date was postponed to one month after it was originally planned in order to allow enough participants to join.

In total, there were 19 participants joining the workshops, each from a different volunteer organization. Most participants were young women, and they covered a diverse range of organization types, development needs, and territories. The range of organizations included government, private sector, civil society, as well as international. Also, their activities covered over half of the 17 sustainable development goals, and there were at least two participants working simultaneously in 18 districts out of the 22 in the country.

In the current circumstances due to the COVID-19 crisis, the workshops needed to be conducted in on-line sessions that lasted two and a half hours each during the span of five Saturdays. While this gave us the opportunity to include participants from different territories and benefit from the interactive features from Zoom and Mural, these tools had a learning threshold and some participants had poor connectivity or only access to a mobile devise. Some efforts to overcome these limitations included providing exercises to learn the use of these tools, but also allowing for “analog” interactions where participants were able to share their ideas via voice, chat or a WhatsApp with assistance from the facilitators.

What were the workshops about?

Each session consisted in sharing tools from the learning cycle methodology used by the UNDP Accelerator Labs. Two key resources used throughout the sessions were The collective intelligence design playbook from Nesta (2020) and the Tool compendium from States of Change (2019) .

Figure 1: Overview of chronology of sessions around the Accelerator Lab’s Learning Cycle

The first session, held in June 5th, introduced participants to the need for finding new ways of solving complex development challenges such as climate change, migration, poverty, security, health, among others. These are challenges where traditional solutions implemented in isolation do not provide results fast enough, because they result from multiple interrelated causes that change quickly. In fact, volunteers are often the first to encounter and try some of the new approaches needed, and they were able to identify many opportunities to innovate.

In this first session, participants were also introduced to a way of thinking about how different types of development interventions may be more suitable based on the degrees of agency. For example, sometimes people can overcome a challenge by themselves. In which case, interventions that increase knowledge or access to a new a technology may be sufficient. For example, teaching a new technique to grow food. Other times, people know what to do, but lack the resources. In these cases, reducing the cost to act can be an effective intervention, such as the distance traveled to see a doctor. Yet, there are situations in which a person cannot overcome the challenge alone. In these instances, facilitating cooperation can help; for example, to encourage a culture welcoming of tourist. Moreover, there are challenges where collective action is not enough. This may require a structural change, such as a change in legislation to provide social protection benefits to refugees.

The second session, held in June 12th, provided participants with guidance on how to map grassroot solutions. They learned about how innovations are new ideas that are successfully implemented to add value. They also learned about the importance of being aware of personal biases and of following ethical principles such as not being extractive when doing observation. Moreover, they were encouraged to be attentive and reflect about how grassroot solutions are simultaneously the response to a need as well as an expression of a deep and potentially different understanding of how the world works. This was exemplified by discussing the different perspectives on how to interpret the value of a mural painted on a street wall by a youth group in a community. Finally, participants had an opportunity to practice solution mapping by conducting a solution safari exercise.

The third session, held in June 19th, introduced participants to techniques to explore new actors, sources and types of data, as well as signals of change. In contrast to the grounded perspective gained through solution mapping, exploration provides a broader perspective to deepen our understanding of the interplay of actors and dynamics involved in a complex development challenge. This way, the relevant components of the challenge can be defined more clearly in order to identify leverages of change.

Photo: UNDP. Participants in one of the workshops.

Participants learned how exploring new actors helps to diversify their perspectives. Using a pre-defined list of different kinds of actors, they were able to identify additional kinds of actors and determine which particular actors were relevant to achieve a development goal of interest. Also, participants considered a list of motivations to engage selected actors. Similarly, they were made aware of the different kinds of data types and ways to collect them, as well as how these sources can open opportunities to fill knowledge gaps, even in real time, about the development challenge. Moreover, participants had the opportunity to practice the exploration of signals of change that help anticipate and prepare for future needs.

The fourth session, held on July 3rd, showed participants how to structure the way to learn which solutions work, and which don’t, through experiments. Experimentation is especially helpful to verify assumptions, to improve an existing solution, and to measure the impact of a solution at a small scale; before investing large amounts of time and resources at a larger scale. Depending on how uncertain is that a solution may work, the methodology of an experiment ranges from initial probing to trial-and-error iterations, randomized control trials, or causal analysis. Moreover, using experimentation to test a portfolio of several safe-to-fail possible solutions is particularly useful for situation when a single solution may not work because the complex development challenge changes quickly and has multiple interrelated causes.

To start thinking about how to design experiments, participants were asked to choose a development challenge and identify its causes. These causes were then grouped into different categories to identify patterns and voids in the understanding of the problem. Finally, participants developed hypotheses about the expected results of actions that addressed some of these causes, considering how uncertain it was such results could happen. Although the exercise stopped at the design stage of experiments, one key idea shared was that, without experimentation, we don’t know if we are doing the best we can.

The fifth and final session, took place on July 10th, and exposed participants to some strategies for “growing” the solutions they have mapped, explored, or tested. The session also included a message from the Resident Representative that reinforced the recognition of the value that volunteers add to achieving development goals and handing out of a recognition for their participation. Participants learned about the importance to communicate their insights and engage key stake holders to amplify the benefits of a solution. Such amplification can grow in at least three directions: inwards, increasing the frequency and intensity in which a solution is used; sideways, adapting the use of a solution to new locations or contexts; and, upwards, when solutions are turned into regulation and are provided with resources. At the end, participants practiced how to build a narrative considering the needs of their audience.

What were some of the workshops’ results?

The value that volunteers can add to the achievement of development goals, by incorporating some methodologies from the Accelerator Lab’s learning cycle, already showed up in the results of the small exercises about solution mapping, exploration of signals of change, and experiment design conducted during the workshops.

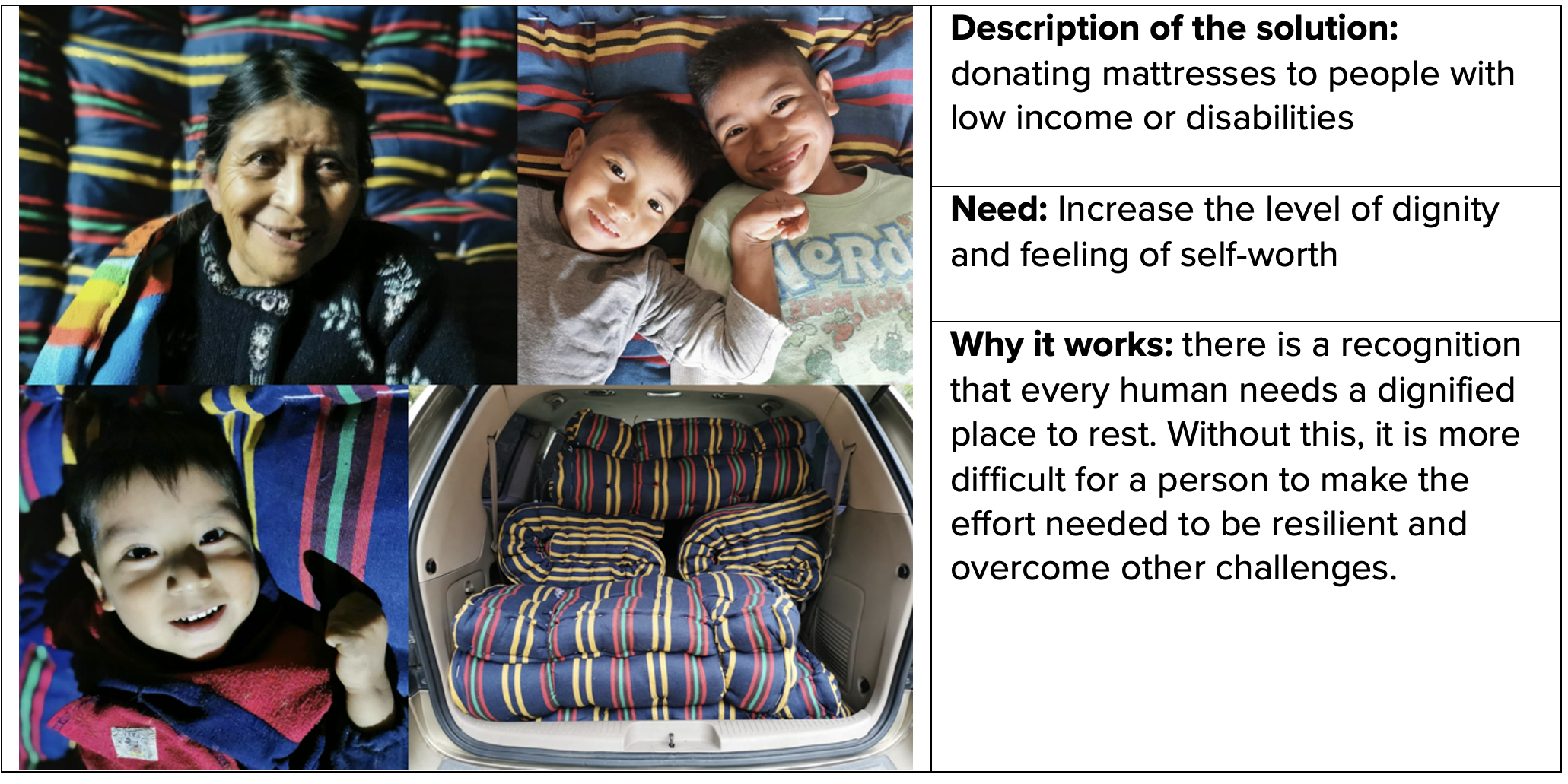

Participants conducted a solution safari exercise in which they were asked to search, within their city, for grassroot innovations. Among other information, they were asked to describe what was the need that the solution addressed and insights about why it worked; reflecting if the solution revealed a different way of understanding a challenge. Indeed, the solutions mapped from the exercise were quite insightful, providing new perspectives. Some noteworthy examples include how collectors of metal for recycling, added the collection of oil since it’s a valuable residue available at the car shops they visit. Also, how the donation of mattress is not only a solution to reduce discomfort, but one aimed at increasing dignity and self-worth, among many other examples.

Box 1: example of a solution mapped during the solution safari exercise

Also, participants conduced an exercise to explore signals of change, which consisted in identifying emerging trends. They were asked to consider what future needs could be anticipated from such signal, how large their impact could be, and how uncertain it was for them to happen. The list of signals of change that volunteers identified also added different perspectives to make the future tangible. Some of the trends pointed out at the accelerated adoption of new communication technologies that are occurring in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic such as: remote working, education, and service provision; as well as e-commerce and subscription to streaming. Others pointed out to trends in social dynamics: attention given to mental health, impacts of grief, increased migration to urban areas, tolerance to diversity, or adoption of cultural influences. And others pointed out changes in the environment, such as the restriction of the use of plastics or food waste, or ways to generate income.

Box 2: example of a signal of change explored by a volunteer

Moreover, participants put in practice the design of a portfolio of experiments to test which actions work to solve a complex development challenge. They followed a template which proved useful to structure how they could learn from actions by breaking actions down into their components and considering their expected results, uncertainty, and causal mechanism. The results from the exercise showed that volunteers are able to think systematically and identify complimentary actions that work together to address a need. Participants proposed portfolios of experiments in topics such as: reducing school dropout, increasing effort from project coordinators, securing food availability, caring for mental health, promoting inclusion, among others.

Box 3: example of a portfolio of experiments

Challenge: Food security |

|

Action 1: Measure anthropometric nutrition indicators |

Description: Create a registry of quarterly anthropometric nutrition measures Expected results: Be able to identify vulnerable cases and track progress Uncertainty: Low uncertainty, depending on quality of measures Causal mechanism: It’s not possible to use resources efficiently without known where the needs and priorities are, or if interventions are working. |

Action 2: Creation of urban gardens |

Description: Organize the community to build urban gardens to grow some of their own food Expected results: Improve the quality, availability and sustainability of food using less economic resources; as well as improving social relations and eating habits. Uncertainty: Medium, depending on willingness to work together and conditions for growing food Causal mechanism: There are existing indigenous practices to grow food which are communal and adapted to the environment that use less economic resources, but have been disrupted |

Action 3: Improve household infrastructure |

Description: Implement improvements to the infrastructure of households Expected results: Increase access to drinking water, air quality, sanitation as well as manage dirt. Uncertainty: Medium, depending on how behaviors adapt accordingly Causal mechanism: Currently, the infrastructure of households limits the benefits of food security exposing people to health risks |

These initial results from the workshops showed that volunteers can indeed contribute to accelerate sustainable development when they incorporate some of the methodologies from the Accelerator Lab’s learning cycle. Volunteers are close to people, in the locations where needs first emerge and are dealt with and are constantly trying new things to help the best way they can with limited resources. Using techniques such as solution mapping, exploration of signals of change, or the design of portfolios of experiments, they can increase their reach and widen our perspective about how to achieve development results.

What additional learnings from the workshop are important to consider?

In addition to learning from the results from the exercises above –as well as from the efforts made to organize the workshops, develop the contents, and implement each session– we think it’s important to reflect about two matters: how to manage conversations about sensitive topics with heterogenous groups, and how to move to action from a training program such as this one.

Along with the diversity of perspectives in heterogenous groups also comes the challenge of managing conversations about sensitive topics. Especially, when addressing different understandings about the causes of development in a country with social polarization. Throughout the workshops we came across controversies regarding “the unwillingness of communities to understand how to achieve progress”, “the benefits of large invasive projects such as mining, hydroelectric plants or agro-industrial activities”, “the counter productiveness of conditional cash transfers”, “the political motivations of conflict”, “the incompatibility between traditional and progressive values”, among others. These suggests that learning how build trust and address sensitive topics between heterogenous groups is a skill needed to overcome barriers to collaboration towards achieving sustainable development goals.

Also, training programs such as this one makes us aware that the move from acquiring new knowledge to implementing actions based on it is not trivial. The workshops did include interactive and practical exercises that even generated initial results; however, while these pedagogical techniques help to clarify and reinforce learning for participants, it is not clear that the new information will continue to be implemented or provide lasting results. To address this, we encouraged some initial collaborations between participants and UNDP’s country office. For example, volunteers contributed with messages for the launch of UNDP’s National Human Development Report and participated in a project to disseminate digital tools. Yet, we understand more work is needed.

Where do we intend to go from here?

Therefore, to give continuity to the network of mini-labs of volunteers initiated by these workshops we are preparing a replication manual. This will empower the first cohort of participants to facilitate similar series of workshops to train other volunteers within their organizations. Also, we are facilitating the co-creation of activities within programmatic areas of UNDP’s Country Office to further involve volunteer organizations through the application of methodologies from the Accelerator Labs’ learning cycle. We hope to showcase the results from these new activities during Volunteer’s Day next December 5th.

Locations

Locations