Credit: Unsplash

This article was originally published on Apolitical.

In a country plagued by years of civil war, rebuilding trust is the first step on the long road towards participatory democracy

This article is written by Ali Muntasir Head of Experimentation and Wigdan Seed Ahmed Head of Exploration, Accelerator Lab Sudan, UNDP Sudan

Effective citizen engagement and participation is often taken as a sign of a healthy democracy. This is particularly true in post conflict settings.

Since modern democracy and the associated political transformations first appeared in the West, the concept of citizen engagement, in its colloquial usage, is often associated with western political philosophy. However, the history of citizen engagement goes back several centuries and has global roots. For example, during the Joseon era (from 1392 to 1897 in the western calendar), in what is now South Korea, the concept was practiced through a process called The Village Assembly or The Citizen Assembly.

In Sudan there is equally a history of tapping into the “crowd wisdom” and to use citizen participation in decision-making that is still practiced in local communities and embedded in local governance structures. A good example is Joudiya, a well-known method for consulting citizens by conducting a community meeting for the wise individuals in the tribe to discuss issues of conflict. The method has been widely used to reduce conflict in western Sudan as a form of crowd wisdom and engaging citizens to be part of the decision making process.

Even though Joudiya and other organic citizen participation mechanisms have been practiced since the colonial era and until today, the practice was never expanded beyond the level of local governance in Sudan. As a result, designing and applying citizen engagement initiatives in Sudan has required unorthodox and innovative methods to overcome the challenge of collecting public opinion and translate it into policy making. UNDP Sudan has leveraged innovative approaches and bridge them with local solutions to voice out citizens' perceptions. The following are the tools we leveraged and some of the lessons we learned.

Before the Revolution: Digital Transformation and Gamification

In the complex context of pre-Revolution Sudan, there were multiple layers of challenges to engage citizens in decision making processes. These challenges were connected to socioeconomic and political conditions that in turn stemmed from historic and cultural marginalisation of demographic and ethnic groups such as youth, gender and certain tribes and ethnicities.

To tackle these complex issues it was crucial to engage citizens and to provide local solutions to their issues. This was especially true for young people because they were perceived as perpetrators of conflict and victims; the challenge was that these same youths had not been interested in engagement due to apathy or because it was considered unsafe to express political opinions.

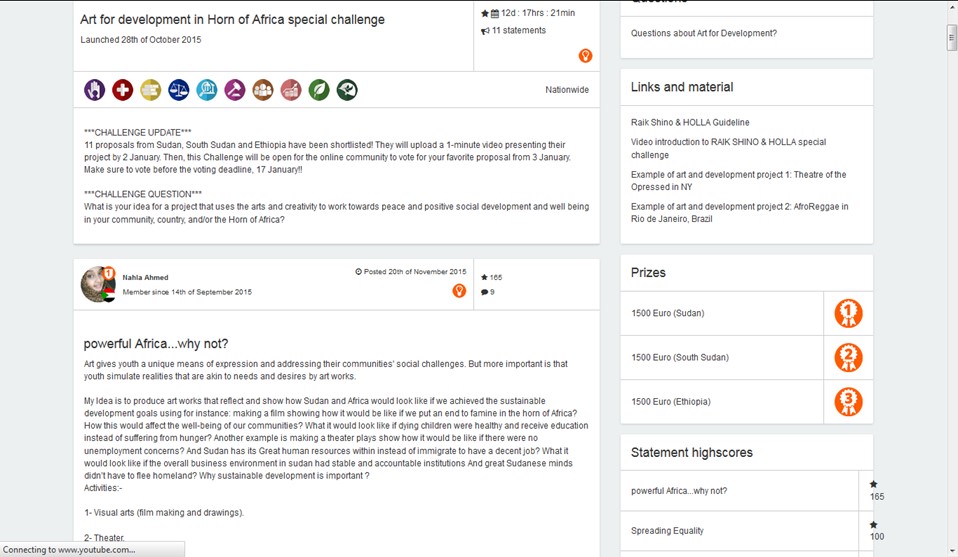

To engage with this problem, in 2015 UNDP designed a platform to engage youth called "Raik Shino" (‘What do you think?’ in Sudanese Arabic), an online dialogue platform that provided a forum for people to creatively interact and discuss the future of Sudan through a gamified dialogue process. The idea behind the gamified platform was to provide opportunities for people to creatively interact and discuss the future of Sudan and encourage citizen engagement in the political dialogue. The process was gamified through a system of point based competition and by incentivising participants through leaderboards and prizes. Although a public platform to openly discuss and reflect, it was a closed online environment where login and game profile names are required to participate in the discussion and have anonymity features to foster a safe space for discussion.

We learned that providing a platform for citizens to freely express and discuss issues that mattered to them, sensitive topics such as Female Gential Mutilation and Peacebuilding came to the surface strongly and uncensored by traditions or state controls. For citizens who could not voice their opinions publicly, Raik Shino proved a much needed safe space for dialogue and sharing opinions to develop a unified vision and solutions for these community challenges in fun, engaging and safe ways. Raik Shino was successful in mobilising public opinion on sensitive and general topics; however, it proved to be difficult to action the collected evidence and data for use in the process of policymaking within Sudan’s previous government due to the rigidity of the structure, a lack of political will and the restrictive views of the government at the time. The Raik Shino platform, although successful, concluded in 2018 - but we continue to channel the lessons learnt to new experiments.

After the Revolution: Nurturing a new relationship between citizens and policymakers

Sudan has recently gone through a national revolution, which resulted in the previous president Omer Al-Bashir being removed from power on the 11th April 2019, marking the end of one historical period for Sudan and the beginning of another. In September 2019 a new civilian led government was announced, but citizen trust in government remains an issue due to previous biases that are embedded in the community. Building citizen confidence in the UN also remains of relevance, considering the UN’s mandate to work and partner with governments. To solve these issues evidence based policies and citizen engagement are crucial.

At UNDP Sudan, this year we initiated the Public Perception Survey in 2020 to gather insights about which development priorities citizens had during the country’s transitional period. These insights will support the new government in developing evidence based policies as well as including the citizens in shaping their own public narrative; however, we first had to get citizens to participate in the survey, which was a challenge due to initial low levels of trust. Therefore, we designed a BI experiment to encourage citizens to participate in the Public Perception survey by designing messages through billboards to nudge them by addressing citizens' biases. The initial learning from this experiment is that area specific messaging can enhance participation since evidence reveals there is bias “ultimate attribution error” towards participants' localities and provinces; however rigorous experimentation will provide more insights towards these bias

Thus the current thinking we are adopting, in a serious attempt to deliver good design by closing the gap between citizens and government, through looking into organic structures, borrow from successful approaches elsewhere and co-designing systems of citizen participation that are adaptive, elastic and purposed for democratisation especially in the transitional period in Sudan.

By doing this, we aim to explore the ontology and epistemology of democracy and experiment with solutions for the problems we encounter. Sharing the work we have done and a glimpse of what we are doing now is our way of echoing the necessity of including people in decision making. And we pin our hopes that our work demystifies the “hows” of mainstreaming positive deviance and outliers as well as defibrillating governance systems of complexity back to life. — Ali Muntasir and Wigdan Seed Ahmed

References;

1- Kunioka, T., & Woller, G. M. (1999). In (a) democracy we trust: social and economic determinants of support for democratic procedures in Central and Eastern Europe. The journal of socio-economics, 28(5), 577-596.

2-Choe, H. (2006). National Identity and Citizenship in the People's Republic of China and the Republic of Korea. Journal of Historical Sociology, 19(1), 84-118

3- Plessing, J. (2017). Challenging elite understandings of citizen participation in South Africa. Politikon, 44(1), 73-91

4- Kyongran Chong, 2018 Revitalization of Ancient Institutions: The 1394 Governance Code for the Joseon Dynasty of Korea by Jeong Do-jeon, A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the School of Languages and Cultures

5- Figueiredo Nascimento, S. Cuccillato, E. Schade, S. Guimarães Pereira, A, .2016 , Citizen Engagement in Science and Policy-Making Reflections and recommendations across the European Commission This publication is a Science for Policy report by the Joint Research Centre (JRC), the European Commission’s science and knowledge service.

6- UNFPA and UNICEF report 2016 Accelrtaing the change by the numbers Annual Report of the UNFPA–UNICEF Joint Programme on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: Accelerating Change.

7- Gianluca Misuraca, Csaba Kucsera, Fiorenza Lipparini, Christian Voigt and Raluca Radescu D1.2 – Annex - IESI Knowledge Map 2015 - Booklet V.1.0 31st October 2015 ICT-Enabled Social Innovation in support to the Implementation of the Social Investment Package - IESI Joint Research Centre (JRC)

8-UNDP newsletter 2018 Issue 2018 - Quarter 3

9- Lewis, Jenny & Mcgann, Michael & Blomkamp, Emma. (2019). When design meets power: Design thinking, public sector innovation and the politics of policymaking. Policy & Politics. 10.1332/030557319X15579230420081.

Locations

Locations