North Macedonia's Accelerator Lab team, as part of the City Experiment Fund (CEF), embarked on a journey to create a dynamic learning portfolio that will address some of the burning issues facing the capital city of Skopje. This blog post is the first in 3-part series that documents our journey to understand how circularity and zero-waste can be achieved in the City of Skopje. The other two posts in the series are available here:

Part 2: Rethinking (bio)waste

Part 3: What is 10kg of citrus biowaste worth?

---

A butterfly can flap its wings in Beijing, and in Central Park, you get rain instead of sunshine.

Most of us have probably heard a variation of this sentence numerous times, but we rarely explore what it might mean for development practitioners. Famously delivered by Jeff Goldblum as Dr. Ian Malcom in Jurassic Park, the sentence’s sole purpose was to explain a nonlinear complex system – the world of dinosaurs – and how that system will eventually interact with humans. Dr. Malcom understood this because he was a mathematician specialized in a branch of mathematics known as “chaos theory,” which grew out of attempts to make computer linear models to predict the weather in the 1960s or, as it was called back then, “predictability in complex systems.”

Like Dr. Malcom, development practitioners sometimes find themselves in a situation where they need to understand and work in a complex system. Our task is to try and understand how different parts of these complex systems work and interact with one another and, by using system lenses – system thinking, not only “see” the complex system but also make sense of the rapidly changing realities in that system, understand the underlying issues and the system dynamics.

One way in which development practitioners can influence social system is through the portfolio approach. This is different from the common use of “portfolio” to describe a grouping of development projects. The portfolio approach is a method of designing and launching multiple small-scale and experimental interventions that have the potential to catalyze a system-wide transformation that is self-sustaining. The goal is to learn what works best by experimenting before focusing additional resources into the most impactful interventions so that their impact can be scaled. A portfolio should also be dynamic and evolve based on learning through the process, seeking out new ideas and actors, and pushing for synergies among multiple interventions.

Understanding portfolios – they journey towards portfolio creation

Throughout the City Experiment Fund project, within 6 months we designed a dynamic learning portfolio and implement options (activities) to test if the complex system of the city of Skopje will be responsive to those interventions over time. In order to do that, we started by defining our intent, developed our hypothesis, and designed a portfolio of options with the guidance from our partners from the Chora Foundation. In addition, we used the Agorà

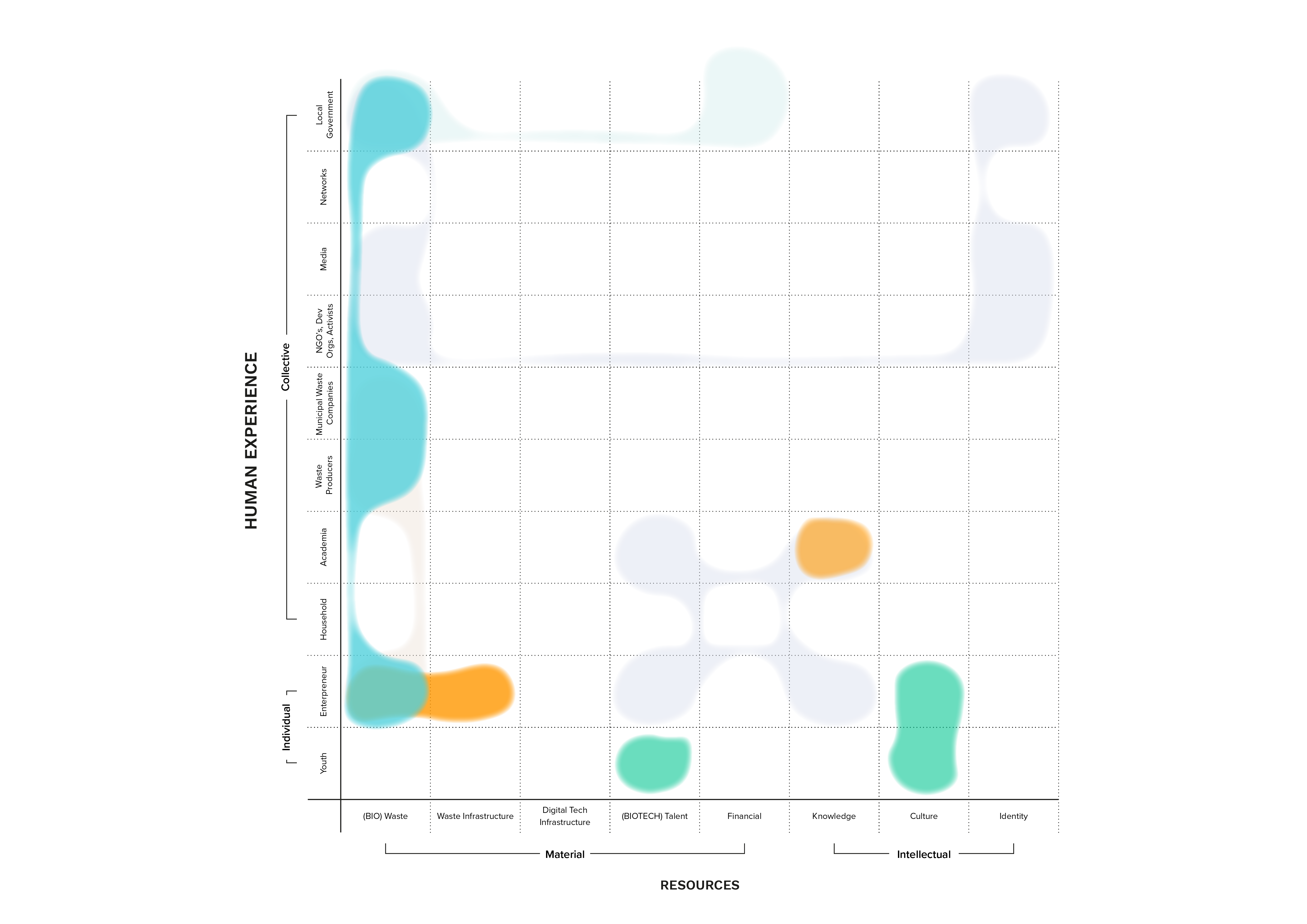

City Transformation Stencil to map the social system and through a series of sensemaking sessions within the Accelerator Lab team and, our Country Office colleagues, as well as city-wide deep listening process to tackle a burning issue for the citizens of the city. In the process of designing the portfolio and portfolio activation, we followed 3 main considerations:

First, we needed to understand who the portfolio should be strategic for. To better understand this, together with our friends from Agirr Lehendakaria center’s, we conducted a city-wide deep listening process to find entry points where we can accelerate circularity. Our entry points were divided into 3 thematic areas, we tried to understand the dynamics of the city, the environment, and the mobility. Thus we conducted ethnographical research on city wide and looked more closely on neighborhoods such as Shuto Orizari, and the Old Turkish Bazar. We transcribed and translated around 420 references points (400 primary and 24 secondary relevant sources) and created relevant quotes and micronarratives. Narratives are simply an expression of the deeply held beliefs of the people. Using narratives, we were able to comprehend what are the mechanisms that formulate the norms of the social system on which we could apply a series of parameters for analysis.

These parameters are closely connected to the second consideration: What objectives should that portfolio have?

Here we focused on UNDP’s strategic goals which were pre-defined and were to help the city recover from the COVID-19 pandemic through greener, inclusive, and resilient local economic development. We started by extracting learnings from the various entry points and found that each had its complexities and arguments for and against inclusion within a UNDP portfolio. The challenge was therefore to design a portfolio that would contribute to all of UNDP’s strategic goals while also leveraging the value of many stakeholders working within a complex system. It is here that we were able to apply systems thinking to help us understand where and how to act for the best results.

We initially considered developing portfolios that would help tackle challenges facing Skopje’s transportation and mobility ecosystem or challenges facing select parts of the city – Shuto Orizari, one of the poorest parts of the city, and the Old Turkish Bazar, a historic quarter and major tourist attraction.

However, after numerous discussions, interviews, and co-creation sessions, we realized that these ecosystems were not the best fit for our experiment. A transportation and mobility portfolio would need to be co-owned by many different stakeholders that, on the long run, could create serious portfolio management problems. At the same time, we found that limiting our portfolio geographically to one or two parts of the city would be too narrow a scope for sustaining a portfolio of options at the Country Office level.

Our Accelerator Lab therefore adopted a third option. While exploring the city’s waste ecosystem, we realized that it had serious potential to generate new jobs, to enhance environmental practices and to provide a space for experimenting with circular economy approaches that could potentially affect all of Skopje’s neighborhoods and residents. Though Skopje’s waste management ecosystem contains many stakeholders, little was being done to transform and improve the system. In other words, we had found the perfect space where we could apply our portfolio approach.

From our interviews with key waste ecosystem stakeholders (micro-narratives), we found that the greatest impact potential was in the biowaste ecosystem specifically as it was almost completely devoid of circularity. Even though the city generates more biowaste than any other type of waste, most of it just ends up rotting in landfills, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions.

Biowaste was therefore the only space where we could achieve all the goals within the framework of this project. You can read our next blogpost in the series, Rethinking (bio)waste, to find out more about how we introduce circularity in Skopje’s biowaste ecosystem.

---

The City Experiment Fund (CEF) is an initiative of the UNDP RBEC and the Slovak Ministry of Finance to support resilience and renewal of cities. Since 2018, through CEF, we have been exploring and experimenting use of systemic approaches to address pollution in Skopje. CEF is a part of Transformative Governance and Finance Facility (2015-2021), and the Slovak Transformation Fund (2021-2024).

Special acknowledgment to Jystina Khrol and Mariela Atanassova for their contributions to this blog series and the CEF portfolio design process.

Locations

Locations