“No somos ni de izquierda, ni de derecha”: Reflections on the role of governance failures associated to the recent social unrest in Latin America

February 27, 2020

In recent months, protests swept across the Latin American region. While there has been extensive commentary on what sparked this widespread social unrest, most of the coverage has focused on the role of social inequality or corruption. Others have rightly argued that there is a “crisis of expectations”, appealing to the Tocqueville Paradox. While these have undoubtedly been some of the most critical factors in driving people to voice their frustrations on the streets, they are not necessarily the only underlying causes, or even the proximate factors.

While there is little data available on the issue, a recent survey conducted by IPSOS helps us to gain some more insight about the governance failures that have become evident in the region. In December 2019, IPSOS conducted a poll of public opinion leaders on the “The Crisis in Latin America” asking country experts to identify the top three reasons for the current conflict in the region. As this #GraphForThought shows, while experts across all countries consistently ranked social inequality and corruption among the top three causes, depending on the country—other factors mattered a lot too. These other factors included frustrations with actors’ inability to effectively or fairly cooperate in the policy arena (institutional weakness, lack of government leadership on issues, and low valuation of the democratic system) as well as their failure to deliver on development outcomes (unemployment/lack of economic growth, violence/crime/drug trafficking, and poverty).

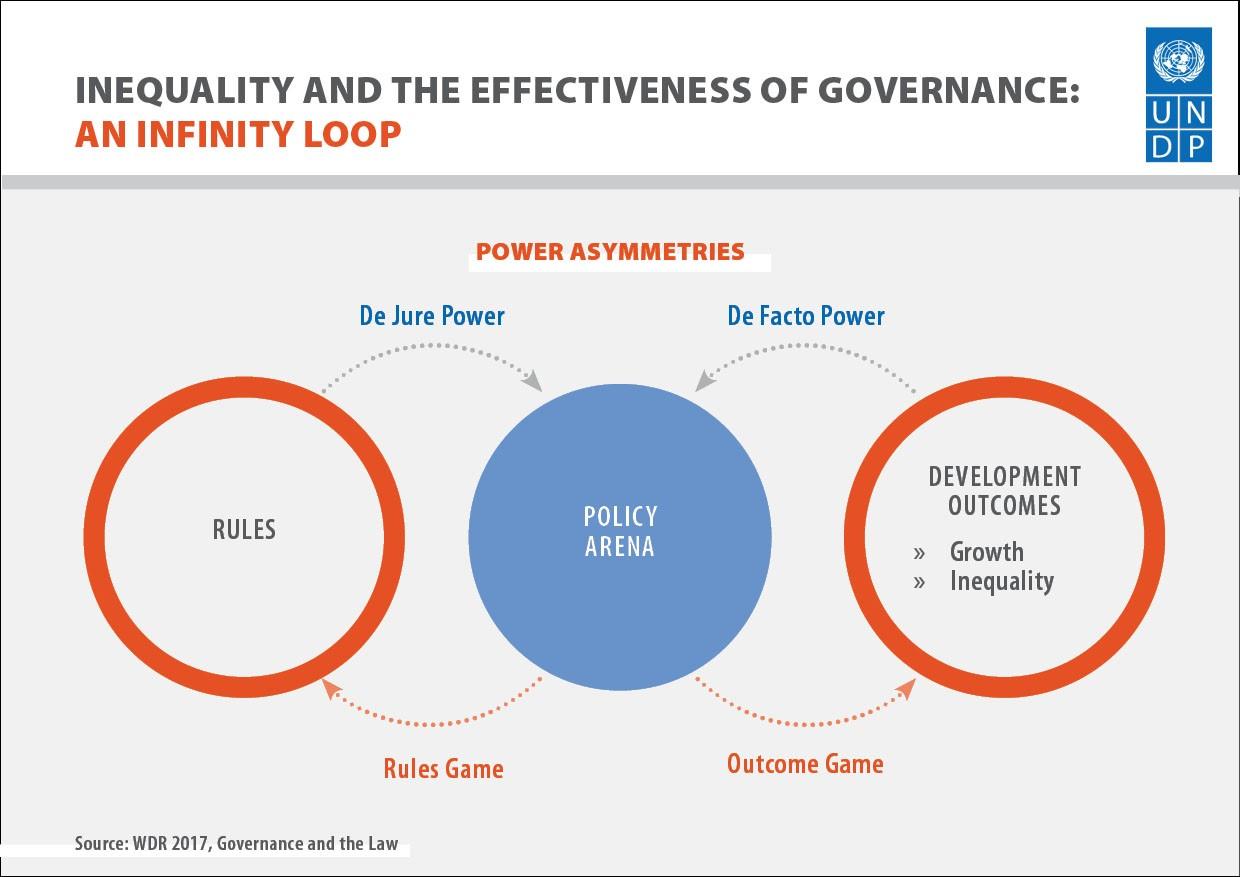

Using the World Development Report 2017’s governance “infinity loop” as a framework, we can see that these issues relate to both sides of the loop—“the rules game” (where agreements on higher-level rules that shape the policy arena play out) and the “outcome game” (where the effectiveness of policies for development plays out). These two cycles (respectively) feedback into long-term governance dynamics by redistributing among the actors the capacity to influence the system. We can think about this infinity loop as describing the ways in which countries are able to process tensions.

From this lens, if we reflect on development results in recent decades in LAC, we see patterns of mediocre and slowing growth; we see persistently high levels of inequality (despite declines since the 1990s); we see a deteriorating fiscal balance; we see high levels of vulnerability among the population (despite declines in poverty); we see an increasing concentration of income at the top; we see disproportionately high levels of violence; and a large youth population in need of employment opportunities. It is thus unsurprising to see the widespread agreement of experts on the role of social inequality in driving the region’s conflict (ranging from 52% of experts in Mexico to 91% in Chile). However, we also see the importance of issues like violence/crime/drug trafficking in Mexico (43% of experts), unemployment and lack of growth in Ecuador (38% of experts), and poverty in Argentina (30% of experts).

Now, if we turn our attention to the rules in LAC, we see patterns of low and declining perceptions of government effectiveness, trust in institutions, and control of corruption. Unsurprisingly, we see widespread agreement of experts on the role of corruption in driving the region’s conflict (ranging from 40% of experts in Brazil to 91% in Colombia). However, we also see the importance of issues such as institutional weakness in Peru (37% of experts), lack of government leadership on issues in Colombia and Chile (22% and 29% of experts), and lack of respect for the democratic systemin Bolivia and Brazil (59% and 37% of experts).

Considering the interplay between outcomes and rules can help us to better understand some of the longer-term dynamics behind the region’s social unrest. If we look at the case of Chile, for example, it can be interpreted as a crisis of expectations generated by the gaps between these two games. On the “outcome” side, Chile experienced high levels of growth and an expansion of the middle class—within a context of persistent inequality. On the “rules” side, these changes were accompanied by new expectations for better governance and better services. In this context, protests calling to fundamentally rethink the constitution, can be read as a demand that solving this problem at the outcome level through a policy solution is not enough—that it also needs to be solved also at the level of the rules.

Whether interpreting the protests through the lens of outcomes or rules —one message very clearly emerges: this is an issue of governance as an underlying factor (with ideology not playing an obvious role). It reflects the growing frustration about the concentration of development gains as well as the concentration of power. As I showed in a previous #GraphForThought, the share of the population in LAC believing that their country is governed in the interests of a few powerful groups is at an all-time high. The demands stemming from this feeling are succinctly reflected in a phrase that has been sighted on multiple protest posters and graffiti walls across the region: “No somos ni de izquerda, ni de derecha, somos los de abajo y vamos por los de arriba,” which roughly translates as “We are neither from the left nor from the right, we are the people at the bottom and we are coming for those at the top.” At its core—the social unrest in the region reflects a frustration with elite capture that undermines the effectiveness of governance.

In order to foster more positive long-term governance dynamics in the region, it is critical that we strengthen the foundations of “representative democracies” (as opposed to what Guillermo O’Donnell calls “delegative democracies”). While countries across the region have undergone a “first” institutional transition from authoritarian regimes to delegative democracies, not all countries have successfully undergone a “second” transition to become fully representative democracies. The critical difference is moving beyond the establishment of mechanism of vertical accountability (in which governments are democratically elected by the people) to also intentionally strengthen and consolidate mechanisms of horizontal accountability (in which systems of checks and balances are effectively institutionalized within government). Without stronger horizontal accountability, countries across the region may continue to struggle in effectively processing the emergent social, economic, and political tensions.

Locations

Locations