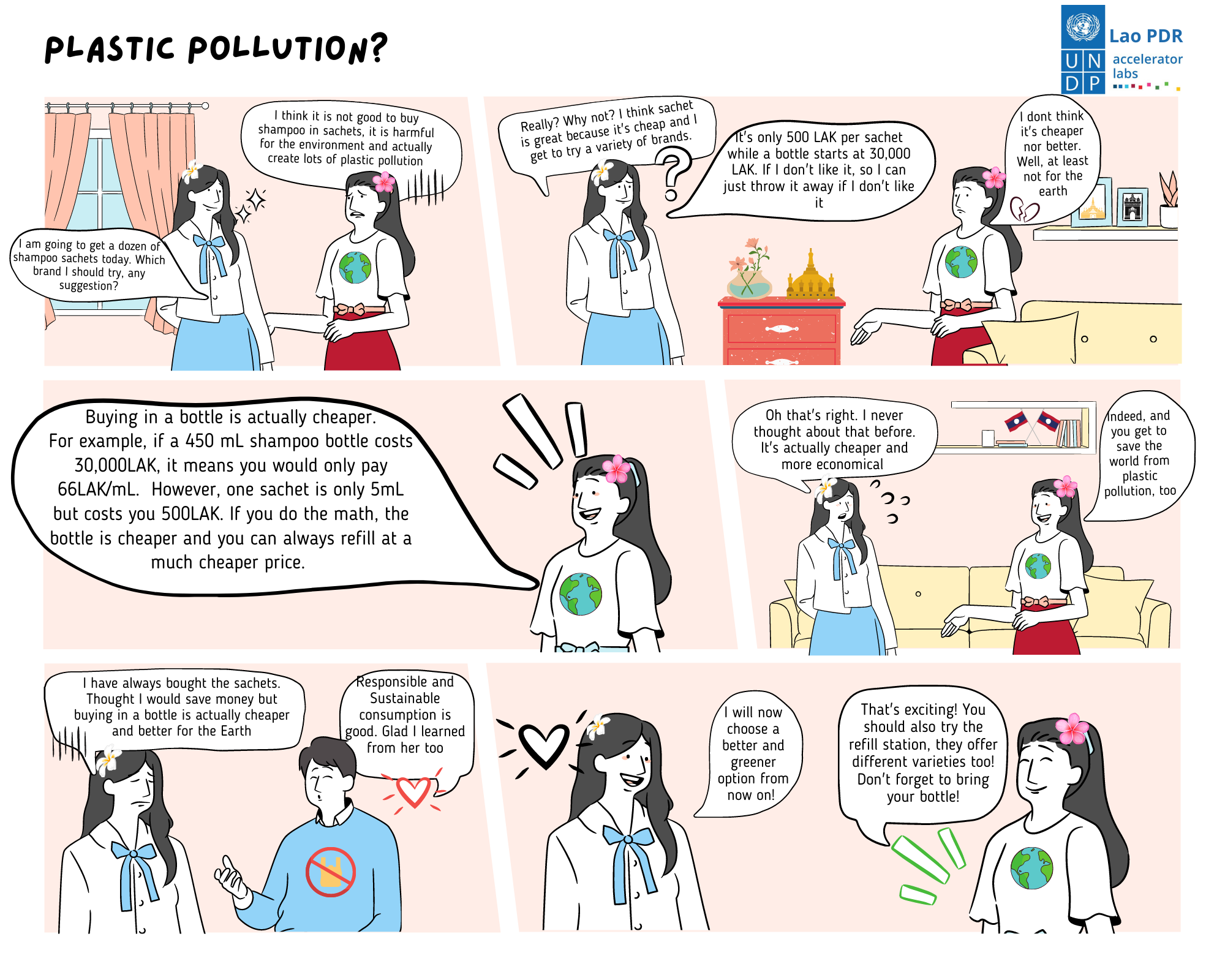

Did you know how big of an environmental problem a small sachet of shampoo could bring?

Single-Use Plastic Sachets: Pollution That Comes at a Cost. Key Learnings from the Refill Station Experiment.

January 21, 2021

Artwork by: UNDP Lao PDR

Intro

We live on a planet where there might soon be more plastic bags than fish in the oceans. A recent news article revealed that microplastic can even exist inside a women's womb.

From the deepest trenches to the highest peak of the tallest mountain, plastic candy wraps can be found, and used plastic bottles are scattered around the summit. Single-use plastic has become an inescapable part of our daily lives that, if left unchecked, could threaten our very existence. We use it for its cheap cost and convenience. We overuse it, take it for granted, and still know little about its multidimensional consequences.

The UNDP Accelerator Lab Network has been working on both macro (creating waste management policy) and microscale (helping informal waste pickers access the proper waste collection system) waste management worldwide. The team in Lao PDR, too, is currently focusing on this topic, particularly on understanding single-use plastic pollution in the capital, Vientiane.

Data from the initial experimentation with Vientiane City Office for Management and Service (VCOMS) at That Luang festival in 2019 and a survey on single-use plastic concluded that more than 73 percent of households in Vientiane do not have access to waste collection services. Additionally, the majority of non-recyclable plastic waste comes in the shape of sachets such as shampoo, soap, etc. Finally, findings from the open burning study at Sikottabong district revealed that most of the waste being burned or dumped into rivers is non-recyclable plastic, particularly those small sachets of consumer products.

Several UNDP Accelerator Labs have been establishing a network and running experiments with the private sector,especially consumer giants such as Unilever. The collaboration aims to facilitate learning on consumer behavior on single-use plastic packaging and discuss the possibility of repurposing their packaging and a way forward to reduce such pollution.

Recently, the Lao PDR team recognized the importance of this collaboration. With learning and experimentation driven mindset, we decided to run a quick behavioral trail to learn whether there is an appetite/willingness for people to change their purchase/consumption pattern. To do this, we set up a Unilever refill station to encourage the replacement of small sachets of previously mentioned products in the city center and the National University of Laos.

Experiment

Before the experiment, our team conducted a small focus group and an online survey to understand the magnitude of the issues. Qualitative research through this focus group (14 people) and an online survey (150 people) identified that most consumers prefer shampoo in sachets because they believe it will help them save money by controlling portions and not wasting shampoo. Moreover, the price is within their weekly budget, whereas a larger container is perceived as too expensive. When asked about how they discard those sachets, 70 percent of respondents admitted to burning them, throwing them into rivers, or dumping them together with other household waste.

Figure 1. Theory of Change

With informative data in hand and a theory of change that, “If people have access to refill station, then they would buy less sachets”, our team was ready to experiment. We designed the experiment to be carried out for seven days: five weekdays at an educational institution and two days over the weekend at the city centre. The main target audiences were males and females aged 18 – 55 in urban areas, namely university students, office workers, and housewives.

The primary objectives of the behavioural insights experiment are to:

· Determine the level of interest in a refill station from the general public

· Find out the motivations of using a refill station from actual customers

· Investigate people perception on single use plastic pollution

The refill store offered different types of personal and household care products such as shampoo, hair conditioner, shower gel, body lotion, dishwashing liquid, laundry detergent, and fabric conditioner. All the products were from Unilever, as they are popular among local consumers. Only the fastest-selling variants were selected for this experiment, as shown in the table below:

Table 1. List of products and their price in LAK

Parkson Mall in the city centre was the first location. The booth was set up near the front entrance and close to the main road in a high traffic area. The mall has many visitors during weekends, mainly teenagers, couples, and families with young kids.

Additionally, we also carried out the experiment at the National University of Laos. Here, students were the main target audience. The refill station was placed at the University’s food court due to its significant foot traffic and popularity as a gathering place.

What did we learn?

At first, very few people were eager to know what the experiment and refill station were about as they were unfamiliar with this newly-introduced concept. A simple booth did not draw much attention. Nonetheless, after the volunteers have explained to walk-by customers about the objectives and the benefits of buying from a refill station, over 70% of store visitors showed excitement and made the purchase.

In fact, sales were low in the first few days but gradually increased as more people became aware of the service, understood the objectives, and trusted this new service due to the legitimacy of Unilever products and the refill station being managed by UNDP; hence, they returned with clean bottles to refill on the following days. This indicates that selecting an appropriate communication channel is a key to effectively delivering messages to the right audience, reaching a level of interest, and growing the customer base.

Speaking of sachet, its low price point and convenient consumption are tempting. However, an economical sized bottle or refilling service offer incredible savings throughout the year. At the end of the experiment, the booth sold 1,016,000LAK (USD$ 102) for 25,400ml of shampoo. It turned out that “Economical value” was the main reason that attracted people to use the service. Below is a table summarizing the refill station experiment result. Shampoo is used as an example as it was the best-selling product during the experiment while also being favoured by consumers in the single-use sachet form.

Figure 2. Collective opinions from customers using service

Environmental impact:

After calculation, the volume of shampoo sold is equivalent to more than 5,000 shampoo sachets. Each shampoo sachet contains 5ml, which means that an economy- sized 450ml shampoo bottle equals 90 sachets. Previous research in other developing countries revealed that most of the collected plastics waste were sachets and were mismanaged, especially in rural areas due to a missing of waste collection services. Hence, they could be dispersed easily, clog up drain pipes and sewage systems, and ending up in our food chain.

Figure 3: Volume equivalent between bottles and sachets

As depicted in the table above: consumers saved ±5,080 sachets from being bought and wasted within a 7-day experiment at just two locations in Vientiane. As mentioned, sales at refill stations are expected to grow as the awareness level rises. Unilever itself has also acknowledged that single-use sachets are not reusable and provide no economic value. ( * Sunsilk has been used to illustrate in the image above as it was the most purchased product during the experiment)

However, even if just these two locations stayed open all year-round, it is reasonable to assume that by saving ±5,000 sachets every 7 days, people could save more than 260,000 sachets in a year.

Hypothetically, looking at a larger scale, if the hospitality industry and each and all population in Laos choose single-use sachets shampoo for their daily use, its environmental impact is alarming. We'll let the following infographic explain.

Figure 4: The assumed amount of wastes in just single-use plastic sachets shampoo per year

Financial impact:

Prior to writing this blog, the retail price per sachet and economy-sized bottle were checked at different retailers. A shampoo sachet of 5ml costs 500LAK (5 Cents), and 450ml costs about 25,000LAK (USD$ 2.5). Large commercial brands, like Unilever, believed they could not effectively reach consumers in low-middle income countries, so they relied on affordability through the "buying less, more often" approach. Hence, they had initiated the demand in this particular market in developing countries with low price points per unit.

Suppose a refill station was made available and accessible for everyone across Laos in one year. In that case, based on data from table 1, a household unit could save 52,000 LAK (USD$5) on shampoo, 125,000 LAK (USD$13) on laundry detergent, and 86,000 LAK (USD$9) on a liquid dishwasher from using refill service or even buy in bottle. This estimation shows that a household would save at least 270,000 LAK (USD$27) if they shifted their buying choices. While this may not be significant savings, but for families living under the poverty line, the amount is quite life-giving. Let’s see what they could do with that amount.

What's next?

The experiment yielded positive results as many consumers were indeed, interested in the model and willing to support it, if the service becomes available. The survey resulted positively on how price and product portion awareness helped people shift their selection process. We could also see that using price to communicate could enhance people’s financial literacy, especially in helping them manage or rethink household budget planning. Results from site survey also confirmed that 88 percent of customers preferred this service due to its cost-saving, while 12 percent wanted to reduce plastic pollution.

A day after the experiment, we held a consultation meeting to discuss the refill station model's results and next steps. A representative from Unilever Lao PDR showed eagerness to expand on the positive results from this experiment. Simultaneously, a few local vendors were interested in setting up stations at schools and university dormitories. Suppose Unilever and retailers join forces in turning this project into reality. In that case, for Unilever, this means a considerable supplement to their current CSR initiative on greener packaging and an opportunity to reposition their brand image. For vendors, especially in rural areas, it would mean a chance to cut logistic costs in coming to town to purchase different sachets.

Even though there is still a long road ahead of us in eliminating plastic pollution in Laos, this behavioral experiment paves the way for the possibility of a plastic-free community. We believe that all plastic consumption comes with a cost, not only financially but, even greater, environmentally. Together, we can become more sustainable by thinking consciously, taking action to eliminate single-use plastics from our own lives, and supporting responsible consumption. And it cannot wait—the planet's future is in our hands.

Written by:

Khavi Homsombath, Head of Experimentation

Bounyali Souvankham, Accelerator Lab Intern

Luckanong Souliyavong, Experiment Consultant for UNDP Accelerator Lab

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the United Nations Development Programme.

Locations

Locations