Part of a UNDP Jordan Blog Series: Exploring the Informal Economy in East Amman

Chapter II: Passing the Mic to Informal Workers

August 7, 2022

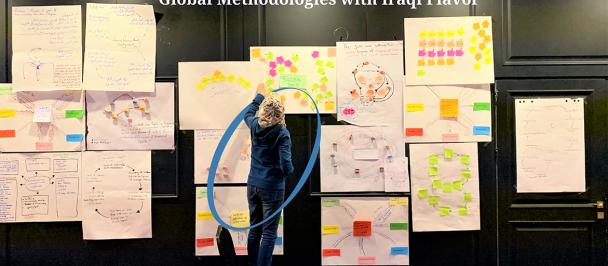

[Some captures of the collective sensemaking workshops with informal workers and business owners in East Amman.] Some captures of the collective sensemaking workshops with informal workers and business owners in East Amman.

In Chapter I of this series, we shared that the informal economy in Jordan is understudied, underappreciated, and underutilized, despite how widespread informal businesses are. In late 2021, UNDP Jordan committed to an exploratory research process in East Amman in order to make sense of this sector and highlighting its value, with the ultimate aim of contributing to the destigmatization of the informal economy and provision of a more dignified life for informal workers. This research was enabled by Jordan being one of the pilot countries for the Informal Economy Facility (IEF), a global UNDP initiative focusing on the protection and empowerment of actors in the informal economy to both benefit from and contribute to development.

So how do you actually go about exploring the informal economy in East Amman?

As an Accelerator Lab network, we prioritize looking for new sources of data, listening to people’s stories and experiences, and learning collectively. To achieve this, the Accelerator Lab Jordan led on (1) collective sensemaking and semi-structured interviews to get an in-depth understanding of the sector from the people who are part of it. The Lab also designed and ran discussion sessions with UNDP and practitioners from various sectors in Jordan to map stakeholders and power dynamics, but this part of the work will not be addressed in this blog.

Hearing from informal workers to frame our research

As a first step, in December 2021, we ran three collective sensemaking workshops (2) with informal workers and business owners in East Amman to understand definitions, perceptions, and “innovations” (3) of the informal economy in Jordan through their perspective and to get some preliminary insights that would frame the remainder of the research.

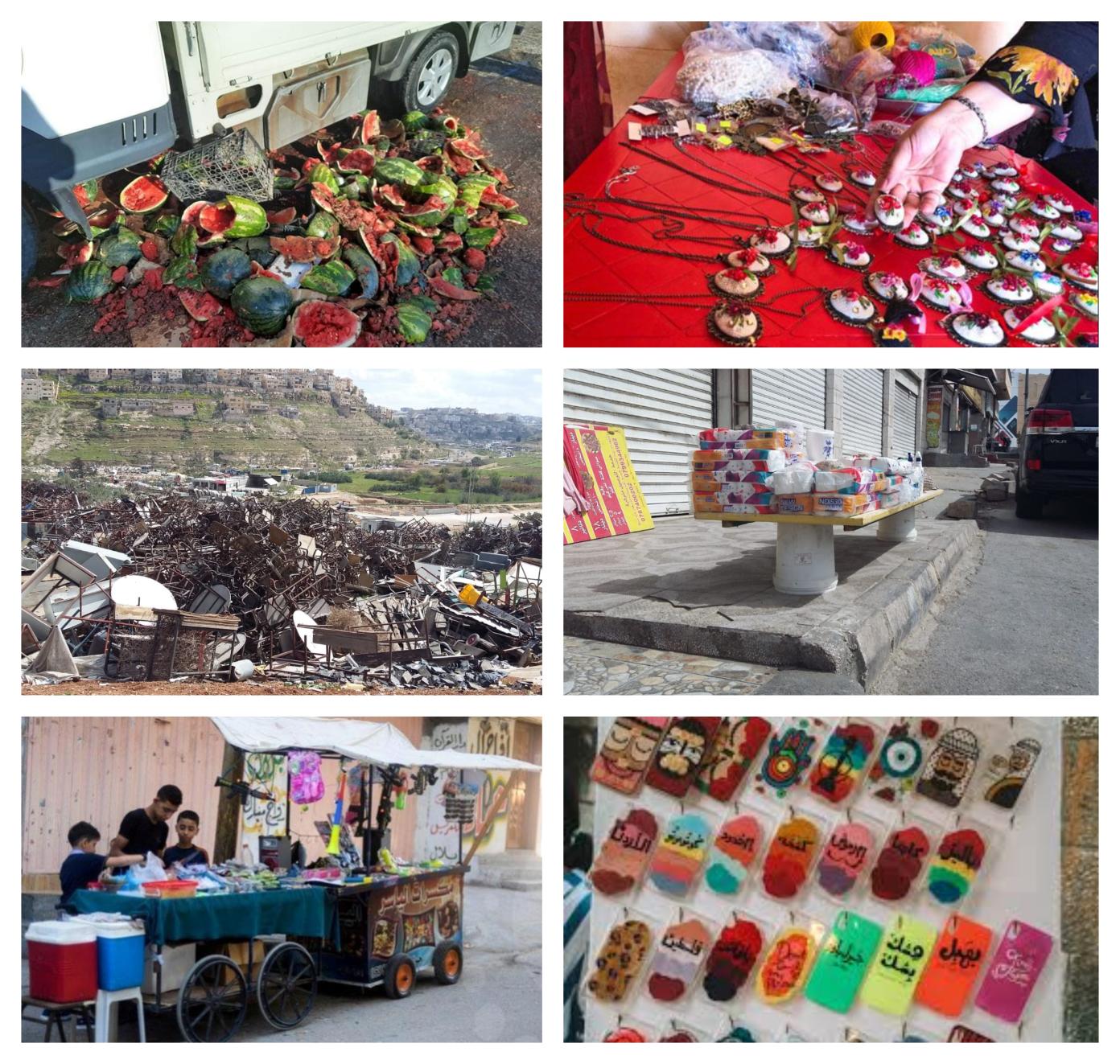

In practical terms, these workshops were small gatherings of 7-12 individuals facilitated by members of the research team. The workshops were designed to be interactive and semi-structured, kicking off with photos of the informal sector (as shown in the images below) for people to reflect on and discuss their experiences. We intentionally did not use the term “informal economy” during the workshop or even when we invited them as it is not common in Arabic, and we wanted to find out what people call this sector they are working in. We also wanted to hear how they describe the informal sector from personal experience. Therefore, we simply spread the photos out on the table, asked each participant to choose one, take some quiet time to study it and reflect on what feelings and thoughts it brought up, and then share with the group. Other participants could then make comments and ask questions and we, as the facilitators from UNDP, built on what we heard.

The workshops revealed that although participants clearly understood that their work does not belong to the public or private sector, they were confused about how to categorize it. They agreed that the lack of social security and health insurance is common amongst the businesses in the pictures and set their work apart from other sectors. They also perceived that their type of work has an expanding presence in the Jordanian economy and is considered a sector of its own. When asked what they would name this sector, suggestions included the left-behind sector, the tireless sector, the new sector, the most-determined sector, and finally, perhaps the most creative name, shared by the Head of Creativity and Challenge Charity Association, a social activist, and an informal business owner, Ms. Enam Okila:

“The illegitimate child that no one wants to take responsibility for”.

Participants affiliated the informal sector with both negative phenomena, such as injustice, poverty, insecurity, exploitation, negligence, child labor, visual pollution, and inhumanity, and positive characteristics, such as pride, honor, and commitment, revealing their reverence for individuals working in this sector. Interestingly, when the participants were asked if they relate to the pictures, they seemed confused, uncomfortable, and hesitant. These feelings could be a result of social stigma around informal work, which are contradictory to the positive characteristics they affiliated with the sector that implied a respect for people working in the informal economy. That said, they all identified with the harsh living conditions and the need to make a living. As one woman said, “I work from home, others work in the street, but we do it for the same reasons.”

It was clear that none of the participants deliberately thought of innovation as something they do or even realized that they might be doing. This could be because they work in conditions of survival and scarcity, and constraints. As for why they are in the sector, some cited flexibility in working conditions, especially for married women, and the feasibility to start self-owned businesses. Others noted that they distrust the government as an employer and a service provider. Still others mentioned lack of education, work experience, and training needed to compete for formal jobs, which means a lack of alternatives to informal work as a way to secure livelihoods.

Building on the insights and digging deeper

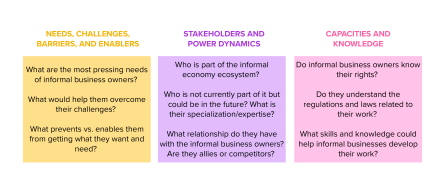

Building on these preliminary insights and a quantitative survey led by a consultant, the Accelerator Lab designed semi-structured interviews focusing on business owners in the informal sector. These interviews aimed to provide insight into the three main areas shown in the diagram below.

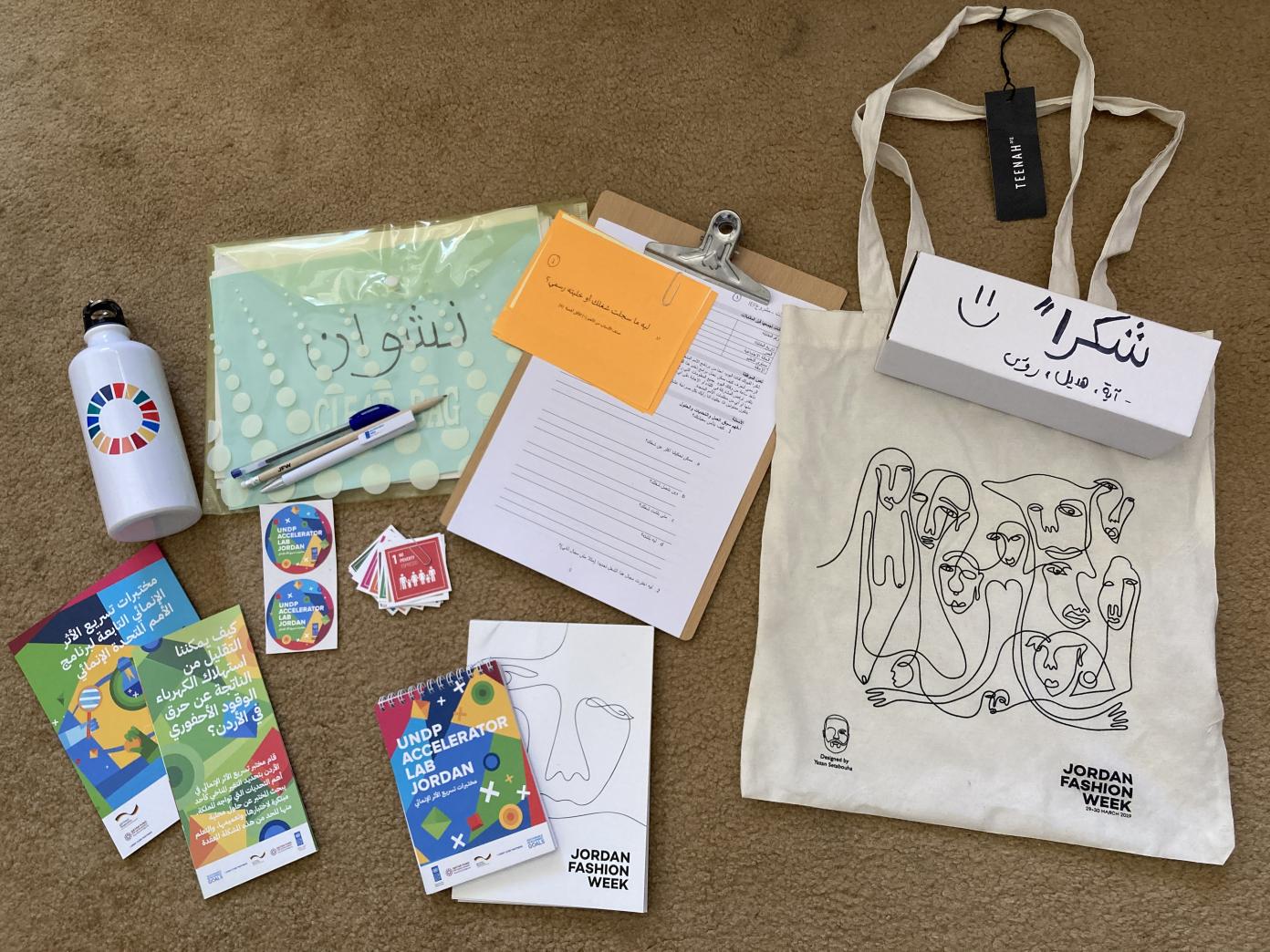

In order to carry out the interviews, we hired three field researchers, who handled recruiting participants, conducting one-on-one interviews on the phone or in person, and uploading the answers into an online form. Each received an interview kit, which included the printed-out interview sheets, sorting cards, a tote bag, water bottle, pens, and some Accelerator Lab merch 😊. Afterwards, the Accelerator Lab team was responsible for analyzing and synthesizing the insights, which also fed into diagrams that visualized the stakeholders and power dynamics. The insights from the interviews were similar to those from the workshops. For example, one woman explained that she is part of the informal economy out of necessity to make a living: "[I work in this sector] to help my husband with the household finances, especially because he had to shut down his shop...”.

[The interview kit provided to the field researchers to conduct semi-structured interviews.] The interview kit provided to the field researchers to conduct semi-structured interviews.

What did we learn from the collective sensemaking workshops and semi-structured interviews?

Both the collective sensemaking workshops and semi-structured interviews were valuable learning experiences for the Accelerator Lab and the IEF team at UNDP. As an Accelerator Lab, we utilized effective methods and concepts, including collective intelligence, power analysis, sorting cards, and hiring a small team of field researchers for a relatively low cost and quick turnround. By setting criteria for participant recruitment, the field researchers were able to ensure diversity and participants of the research target population. One shortcoming, however, was that we did not reach certain informal business owners like artists, graphic designers, and translators because these field researchers did not know any. Collaborating with the field researchers tremendously improved our experience and results and highlighted the importance of building a community and “extension” for the Lab. As the Accelerator Lab Jordan, we are now developing a plan for “community researchers”, which will take into consideration the experience of collaborating with trained field researchers who were professional, dedicated, and quickly able to mobilize and complete the work on time after an unexpected and sudden change in plans.

(1) The Accelerator Lab played a role as part of a larger IEF team at UNDP Jordan, which is led by the Policy Advisory Team and includes the Innovation Specialist, Inclusive Growth and Livelihoods program, and Gender Specialist

(2) Refer to the definitions of collective intelligence and sensemaking in Chapter 1 of this series to understand what we mean by “collective sensemaking workshops”.

(3) For the purposes of this project, “innovation” is defined as: [“implementation of a new or significantly improved product (good or service), or process, a new marketing method [e.g. a novel product design], or a new organizational method in business practices, workplace organization or external relations” (OECD/Eurostat 2005, p. 46)/ OECD/Eurostat 2005. Oslo Manual: Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data, third edition (The Measurement of Scientific and Technological Activities). Paris, OECD Publishing.

We are now coming to the end of the IEF exploratory research and are looking forward to sharing the outcomes. Stay tuned for Chapter III to find out what we learned!

Locations

Locations