One of the many repercussions of COVID-19 in the Pacific was putting food on the table. Loss of tourism jobs, supply chain disruptions and limited movement exacerbated the existing gaps in the food and agriculture ecosystem. However, on the positive side, it created the ‘backyard farmer’ who spent their time in lockdown, unemployed, but working their land to grow vegetables, fruits, and herbs. This growing trend was backed by free seedlings distributed by government and skilling by non-governmental organizations. In this environment, UNDP Pacific has been exploring innovative models for increased food security in Fiji and Vanuatu.

Early consultations to test appetite for hydroponics systems (Photo: Sunishma Singh)

Informal settlements in Fiji were particularly hit hard during COVID-19. They had limited land to benefit from government support. In our exploration with UN Habitat, we identified the need for increased food access, availability and affordability. Hydroponic kits could be a potential solution serving the interim and possibly long-term needs of households in the informal settlements. We opted for Deep Water Culture (DWC) kits, which are mobile, compact, easy to build at home and scalable without high capital expenditure. The aim was to provide an avenue for growing nutritious food right at their doorstep. After understanding food habits, we narrowed down on cabbage which was versatile in its use across multiple ethnic communities and filled the nutrition gap when food supplies were low. We selected 50 households in five informal settlements across three locations using a stratified sampling method. Most of the selected households had demonstrated interest in growing their own food and were actively involved in soil farming.

After training in using hydroponics, each family was given a kit with 12 seedlings and nutrients to be mixed in water.

Training in informal settlement in Lautoka, Western Division, Fiji (Photo: UNDP / Zainab Kakal)

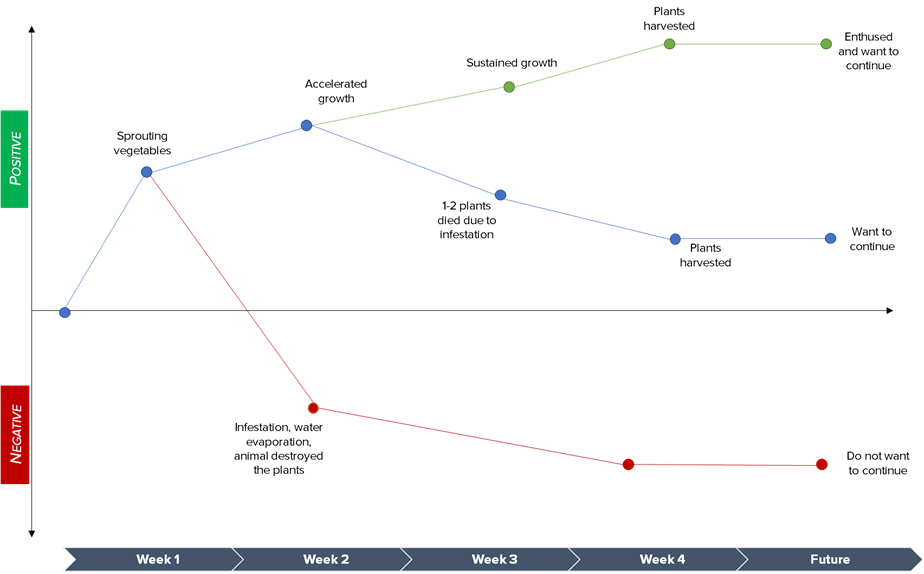

Our user journey mapping showed three types of user groups emerge: those who had 90-100% rate of success (denoted in figure in green), those who had around 80% success (denoted in figure in blue) and those who had 10-20% success (denoted in figure in red). Those groups that enjoyed a good harvest showed interest in continuing with hydroponics.

.

Cabbage seedlings in week 1 (Photo: UNDP / Zainab Kakal)

Fully grown cabbage seedlings in week 4 (Photo: Geeta Singh)

What worked? Novelty, cyclone proof, space efficient, quick growth, and human ingenuity

The novelty of using water to grow food generated high interest and spiked initial uptake. The simplicity and sophistication of hydroponics was attractive compared to soil farming, which needed toiling and hard work.

Equipping each kit with wheels, which allowed for easy movement proved useful during our trial. At the end of the first week, Cyclone Yasa hit the Pacific and several households brought their hydroponic kits inside their homes before they evacuated to higher ground. While their backyard gardens got flooded, the kit was safely stored at an elevation.

Backyard farm of farmer in Kulukulu (Photo: UNDP / Zainab Kakal)

Farmer who used hydroponics after the trial period (Photo: UNDP / Zainab Kakal)

Almost all participants remarked that cabbages grow faster and bigger using hydroponics. They also use lesser space in a kit compared to growing them in soil. This positioned hydroponics as the farming option of choice. In one of the settlements, more than 90% of the households had a full harvest making it a positive deviant. This settlement was located under the sand dunes and did not have favorable soil for farming, which made hydroponics more attractive as an option. This settlement for most was keen to continue hydroponics and grow different fruits and vegetables using the kits.

Those families that did well were supported by their family members in maintaining the plants. Some built a makeshift shade to protect the plants from the harsh summer sun. Some moved the kit indoor during afternoons. Some build an elevated platform with stones to protect the kit from pets and animals. This ingenuity was key to their success.

Makeshift mesh to protects plants from animals and direct sunlight (Photo: Sunishma Singh)

What didn’t work? Design, infestation, accessing nutrients, costing and inability to diversify

Kit repurposed to store clothes (Photo: UNDP / Zainab Kakal)

Kit repurposed for storing toys for children (Photo: UNDP / Zainab Kakal)

The kits used small stones to block alien particles from going into the water. In 2 settlements, the stones did not act as an effective barrier and led to infestation. It also did not prevent the water from drying up under the sun. This caused most of the plants to die. In the next iteration, the kit would benefit from foam, which could be an alternate barrier.

Stunted seedlings and infestation were two key reasons why people lost interest in hydroponics. As shown by the user journey mapping, this happened in week two demonstrating the need for time sensitive support, which can improve adoption rates in the long run.

Stunted and infested seedlings in week 4 (Photo: Geeta Singh)

As the nutrients for hydroponics were not available in mainstream stores, several households who wished to continue hydroponic farming abandoned its use. On our visit to some households, we found the kits repurposed as storage for food, clothing, and assorted items.

The retail price for the kit and the nutrients were not competitive enough to shift completely to hydroponics from soil farming. While it was an attractive option during COVID-19 when food prices escalated, it is unable to sustain the interest in the post COVID-19 time.

As nutrients used in hydroponics are customized for specific plants, the lack of flexibility to grow what one wished was seen as cumbersome and inconvenient.

What is next?

What is clear to us is that hydroponics can be an effective complement to soil farming. Its efficiency and faster growth lend itself to be used for planting vegetables that are consumed often.

For greater uptake, hydroponics could be offered as a service rather than a product. This allows consumers access to nutrients and regular support. In informal settlements, this could be used at community level for greater joint benefit.

---

Footnotes

Many thanks to Mohseen Dean, the UN Habitat team including Inga Korte, Sara Vergues and Resilience Officers from Lautoka, Nadi, Sigatoka and Lami Town Councils for their support.

Locations

Locations