Figure 1: Aerial view of Fongafale. (Source: Adapted from theguardian.com – Eleanor Ainge Roy and Sean Gallagher.)

The people of Tuvalu generally have a strong connection to their land. The local catch phrase in Tuvalu is that “Tuvalu is sinking, and it is slowly disappearing”. Seen from above; Fongafale - the urban hub of Tuvalu looks like paradise (refer Figure 1). However, Tuvalu as a small island state is resource poor, least-developed country which is extremely vulnerable to the effects of climate change, specifically sea level rise. Although Tuvalu is a member of the UN, the nation was not ranked in the 2019 Human Development Index (HDI) report, due to lack of data.

My Inaugural Mission to Fongafale

My first UNDP mission as the Head of Community Research and Ethnographic Solutions Mapping was a one week Solutions Safari escapade to Fongafale, Funafuti in Tuvalu (our ‘deep demonstration site’) to further explore our frontier challenge on ‘Climate Security for Low Lying Coastal Areas/Atolls’, and source local mechanisms for coping with the effects of Climate Change.

During the safari, I was actively engaged in gathering intel from the Fongafale community on the following six key thematic areas: (i) Vulnerability to Sea Level Rise, Cyclones, Tsunamis, and Droughts, Flooding/King Tides, (ii) Food and Water Security, (iii) Flora and Fauna/Biodiversity, (iv) Climate Refugees, Loss of culture and Identity, (v) Marine Hazards, and (vi) Disease, Health and Nutrition. These are areas of common concern for almost all low-lying atoll states around the globe, and they require new approaches and solutions.

Solutions Safari Methodology

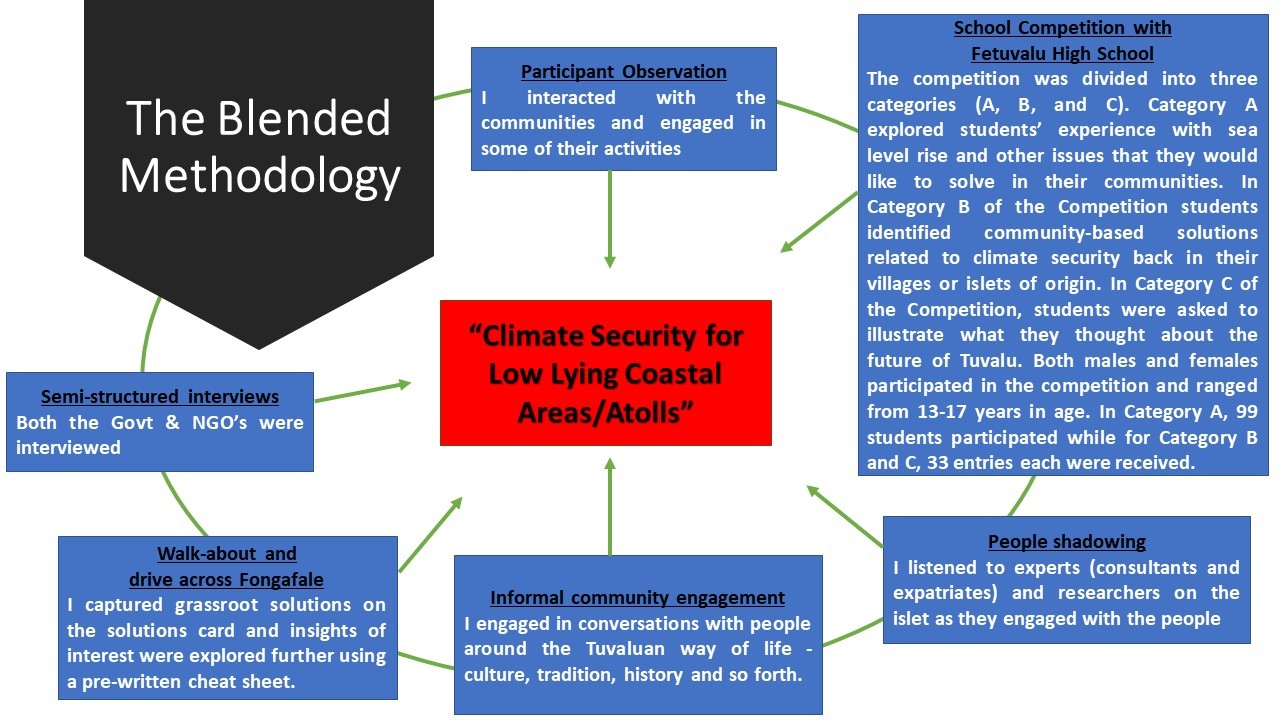

I devised my own customized blended method (described below) of problem-solving approach for the Solutions Safari on Fongafale, using concepts from the Ukraine AccLab Community Safari and the Solutions mapping tools that we were coached for in Quito, Ecuador during the onboarding Bootcamp. This approach was collaborative in nature, action-oriented, and integrally anthropological / ethnographic and was made possible by combining research related tools such as Participant Observation, Informal Community Engagement (refer Figures 2 and 3), and Semi-structured Interviews that I utilized previously as an academic with that of Solutions Mapping tools such as People Shadowing and Walk-about / Drive across Fongafale, commonly utilized by Solution Mappers in the Innovation space.

Figure 2: Informal Engagement with handicraft ladies (Photo: Mohseen Dean)

Figure 3: Conversation in the night with ladies sewing pillowcases (handmade) (Photo: Mohseen Dean)

A School Competition was an additional tool that I later introduced into the methodology to explore from the students - the future generations and leaders of Tuvalu, what they perceived about Climate Change and its impact on their nation. The following illustration provides a list of tools used to craft the blended methodology (refer Figure 4).

Figure 4: List of tools utilized and the value they created during the solutions safari.

This customized methodology helped elicit information relating to what we didn’t know previously about our frontier challenge and our ‘deep demonstration site’. It allowed us to triangulate data gathered, and the intel generated from it supported identifying possible entry points for future experimentation related to our frontier challenge.

Possible Entry Points

From the intel generated, we found possible experimenting entry points to be mainly grounded into two thematic areas: (i) ‘Vulnerability to Sea Level Rise, Cyclones, Tsunamis and Droughts, Flooding/King Tides’ and (ii) ‘Food and Water Security’, with a stronger focus on the latter.

Given Tuvalu’s status as ‘resource poor’ and faced with extreme negative climatic conditions, an unfavorable geomorphology, and its dependence on processed and imported food items (a major contributor of non-communicable diseases) and foreign food aid, further analysis of the data and intel pointed towards agriculture-based interventions that can help support communities threatened by food scarcity.

Experiments such as hydroponic farming, high-raised bed farming systems, diversified farming systems, and urban and backyard gardening which require only relatively little financial or technological inputs seems viable and promising.

The Spin

Unfortunately, any such interventions are currently halted as we repurpose our energy to respond to the unprecedented global Coronavirus or Covid-19 pandemic and its impacts in the Pacific region. With Covid-19 outbreak causing a global health crisis as well as a development and inequality crisis, food scientists and academics are already warning that food supplies around the world could be massively disrupted. As borders around the world are closed and countries succumbing to lockdowns, a drop in the production and manufacturing of food is on the horizon, the future of food security looks bleak.

At a global scale, chances are that this pandemic will increase the number of people suffering from hunger and undernourishment. Post pandemic, the world might see a ‘silent war’ fought over food supplies just like the silent war currently being fought over Personal Protective Equipment’s (PPEs) and pharmaceutical supplies.

At the regional and national levels, we ought to be prepared for such a ‘invisible disaster’ unfolding secretly, and this could be more disastrous then the ‘perfect storm’ of the 2007-2008 that sent an additional 75 million people into the ranks of the ‘world’s hungry’. Hence, a stronger movement, fighting the current pandemic with facts, science, integration, solidarity, and technical cooperation can lead to prosperity for all.

In my next blog, I will be specifically focusing on insights generated on the theme: Vulnerability to Sea Level Rise, Cyclones, Tsunamis, and Droughts, Flooding/King Tides.

Locations

Locations