By Hadil Habashneh, Head of Experimentation in UNDP Jordan’s Accelerator Lab

Changing Spaces to Change Behaviors

November 30, 2022

Late 2019, the Accelerator Lab Jordan’s frontier challenge was traditional gender roles and harmful discriminatory social norms, as we noticed how these roles and norms were shifting and behaviors were changing as a result of the pandemic lockdown measures. Accordingly, the Accelerator Lab experimented on nudging people to balance carework responsibilities, specifically men to contribute to the care economy and taking a more prominent role in household chores through a Twitter campaign called “Our House, Our Responsibility”.

The experiment’s results were not what we hoped for, nudging was not sufficient to entice a behavioral change in a short period. We learned that nudging should be supported by another tool for behavioral change in regards to shifting gendered social norms., and to decide on the proper next steps, we needed to dig deeper for local solutions that tackle gender inequality in Jordan, and so we did. We mapped several local solutions and analyzed collaboration possibilities. We decided to collaborate with Society for Aid, Improvement, and Bridging (SAIB), a local initiative-turned-NGO. SAIB’s work focuses on the effects of spatial design on behaviors, believing that people shape the surrounding environments, as much as the environment shapes them.

SAIB’s work is based on the Behavior Settings Theory. The central concept of this theory states that a person’s psychological well-being, the role they take, and the rules they obey are entirely determined by the occupied environment rather than their individual characteristics (1). The theory was developed in the past 50 years and has been further explored by the work of Zaid Awamleh, co-founder and director of SAIB, in his research: “Refugee Camps as Behavior Settings”.

In our experiment which is based on the Behavior Setting Theory, we picked three households, and insured diversity in the families by choosing them based on the family’s size and the ratio of male:female in its members, two families were on the opposite extremes on each criterion, and one was in the middle. For example, one of the families had all-boys children, another had all-girls, and the third one had both boys and girls. As for the family size, one family consisted of three children in addition to the parents and grandmother, another consisted of ten children besides the parents, and in between them was a family of five children and the parents.

“What people say, what people do, and what they say they do are entirely different things” - Margaret Mead. Therefore, we planned to shadow the family members in their daily routines. Of course, an outsider shadowing them would create a bias in their behavior. To avoid this bias, we worked with members of the families or community to shadow different family members. They kept a time-log of where each family member was at a given time and what activities were carried out. As per the Behavior-Setting Theory, a deeper understanding of the family member's psychological well-being was done through interviews, to ensure that the recipient is in a stable psychological well-being shape.

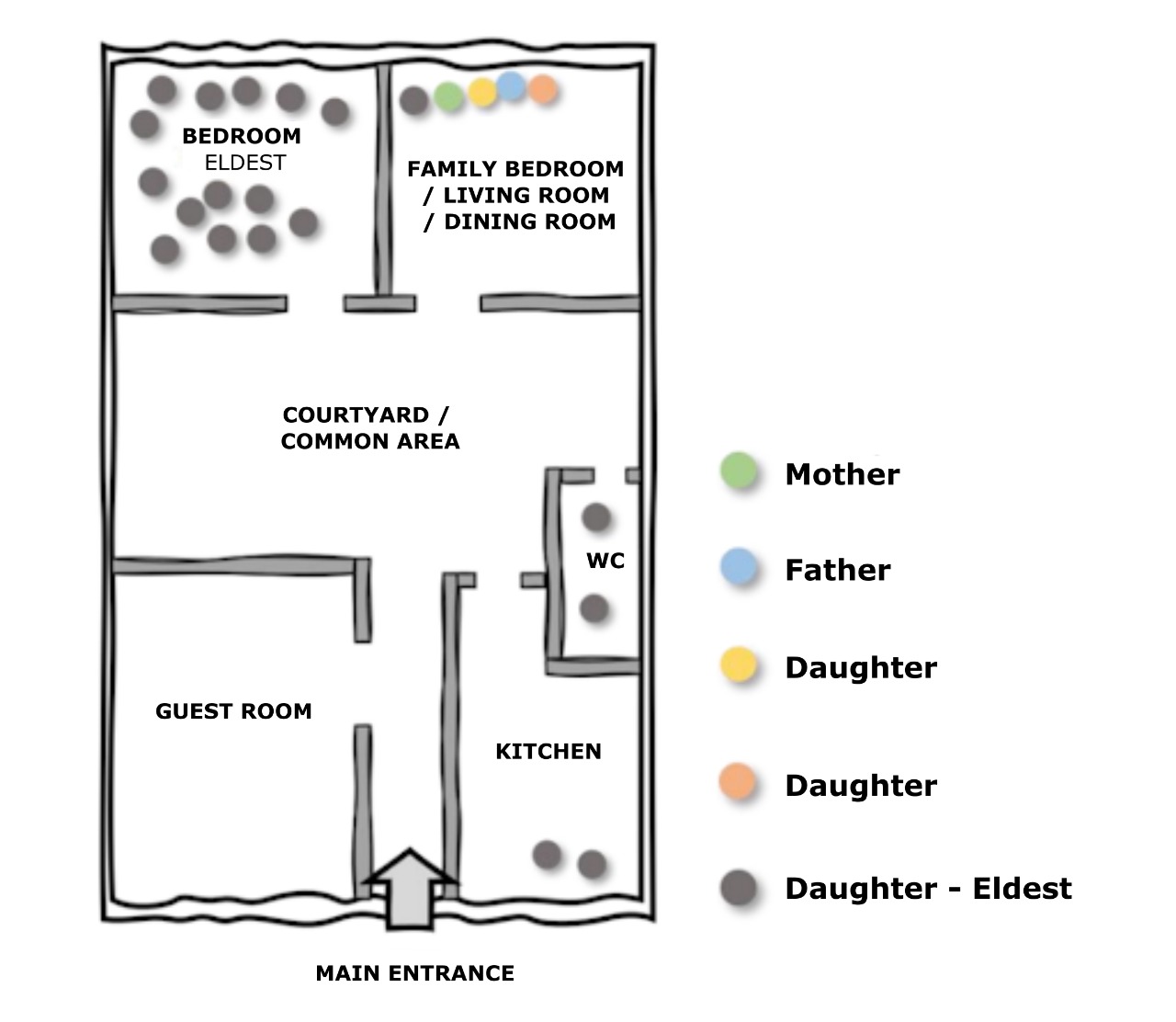

The shadowing lasted for two weeks, and after that, the Accelerator Lab and SAIB analyzed the data. One of the insights was that the parent’s bedroom was often used for many purposes, like studying, playing, hosting visitors, and sleeping. This meant that the mother did not have a her personal space, to do self-care activities, or to invite her friends and socialize with them in her house. In another house, the laundry room and kitchen were almost exclusively used by women, with minimal exceptions. Because these areas were strictly for women, the activities that are carried out in them also became exclusively for women.

Mapping of a participant’s (eldest daughter) presence around the house on a normal day. Figure created by SAIB

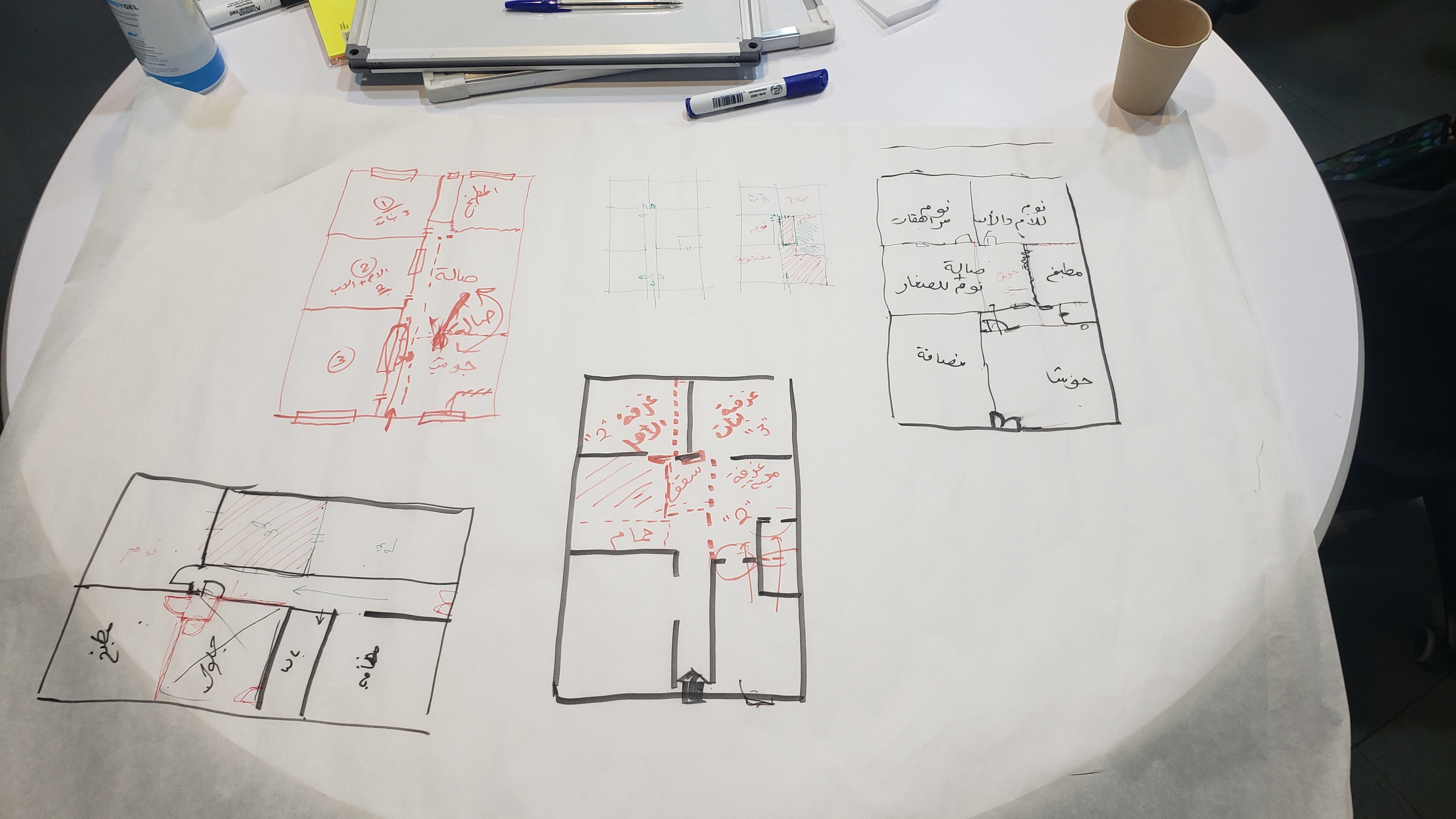

After the analysis, the Accelerator Lab, SAIB, and community members met in a co-design workshop. After breaking the ice, we started by reviewing the data analysis for the first home and brainstorming what spatial changes could be introduced and how these changes may influence behaviors. Considering the constraints, and after rounds of discussions, we agreed on the intervention that will take place. For example, an intervention that we agreed on in one of the houses was to open the living room to the kitchen. We believe that by doing so, the kitchen would no longer be associated exclusively with females in the house, as the living room is a place where all family members gather and use.

Photos from the co-design workshop

We recently started implementing interventions in the households. Starting off with exterior changes and then to interior. We estimate that this step will take us until the end of July.

Photo from the ongoing implementation phase

Once we finish, we will give people time to use the space. Towards the end of this year, another shadowing is planned to study how these spatial design interventions impact the families behaviors. We will continue to update you on our journey in testing to see if taking down the physical wall will also take down the stigma around gender norms and roles, so stay tuned for our next blogs!

(1) Barker & Wright, 1955; Barker, 1968; Barker & Schoggen, 1973; Schoggen, 1983; Wicker, 1979, 2002, 2011, 2012.

Locations

Locations