The first step is to explore the different ways a driver might manifest in the future and prioritize those that are most critical for further analysis. Drivers of change are dynamic forces, and their evolution can lead to a variety of ou comes depending on contextual factors, societal choices, and external disruptions. This step helps the team artic late these possible outcomes and focus on the ones with the most potential impact.

During this step, it is crucial to avoid self-censorship and think freely, even about outcomes that might seem unlikely or unconventional. This is a common pitfall in foresight exercises—teams may focus only on “realistic” scenarios or those that align with current trends, inadvertently reinforcing internal blind spots. Encourage the team to consider “wild card” possibilities or surprising outcomes, as these can reveal biases and help uncover hidden vulnerabilities or opportunities.

For example:

- A team focused on urban migration might overlook the possibility of reverse migration to rural areas due to unexpected breakthroughs in rural development technologies or policies.

- A driver like “emerging technologies in governance” could yield an unexpected outcome , such as AI-driven decentralization, which could completely reshape political systems.

Thinking beyond what seems immediately likely ensures a broader exploration of possibilities and prepares the team for a wider range of futures. This openness can help mitigate bias and bring previously overlooked but important dynamics into the conversation.

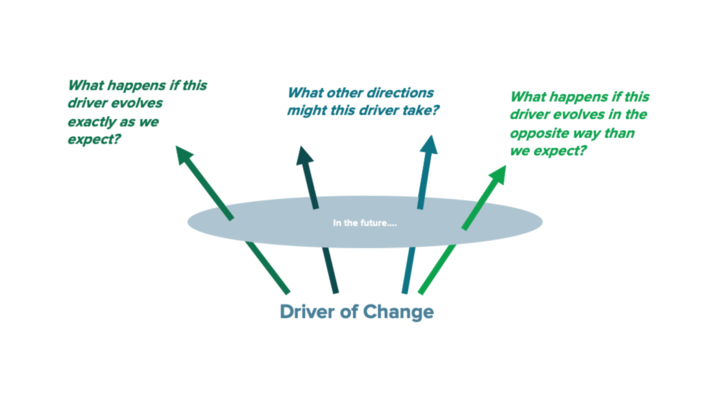

Thinking Through Driver Outcomes

To explore driver outcomes, consider asking the following questions for every driver:

- What happens if this driver evolves exactly as we expect?

- What happens if this driver evolves in the opposite way than we expect?

- What other directions might this driver take?

An example:

Suppose we were considering a driver of change “Climate-Induced Rural-to-Urban Migration”.

The mainstream thought within UNDP or the wider UN system could be that migration to urban areas will continue increasing steadily, putting pressure on housing, jobs, and services. So in ten years, the population in the urban areas would double.

We urge you and the team to consider what would happen if the exact opposite of your expected outcome occurred.

Could it be possible that over time, the lack of adequate housing and employment opportunities slows down migration? Or, with the spread of better rural connectivity and education, urban migration could become unnecessary, which could mean that rural-to-urban migration stagnates.

It is natural to consider these ‘alternatives’ implausible, but think back to the signals from your horizon scan. Is there any evidence that something like this is happening—if not in the country context, then in the regional or global context—that might be a harbinger of possible things to come?

Consider other alternatives, too. What if change happens in the same direction you expect but twice or thrice faster than you expect? Is it possible, for example, that climate disasters accelerate migration, overwhelm urban systems, and create unplanned settlements?

This step may be the most challenging for many team members. However, avoiding self-censorship is critical to achieving the true value of this exercise.

In the next step, each of these outcomes will be evaluated to determine whether it truly represents a risk to development and whether any of them should be dismissed.

Move on to Step 2: Prioritizing Driver Outcomes

Locations

Locations