A (virtual) Journey of Immersion into Solid Waste Management in Tonosí - What did we find?

A (virtual) Journey of Immersion into Solid Waste Management in Tonosí - What did we find?

March 31, 2021

It was December 2020. As the recently inducted Accelerator Lab, we packed our bags and turned on our ‘fast and curious’ mode to immerse ourselves in the world of solid waste management (SWM) in Azuero. Together with UNDP’s Azuero Sostenible project team, the Ministry of the Environment, and the Municipalities of Pocrí, Pedasí and Tonosí, we started our journey with our first question: what does the SWM system of Azuero look like?

Before we move on, there is something you need to know: more than looking for unicorns, silver bullets, and contest winners, we are creating learning cycles to build actionable and collective intelligence, bet on solutions from grassroots innovators, and accelerate learning on what works and what doesn’t for sustainable development through experimentation.

Let me tell you more about our story so far:

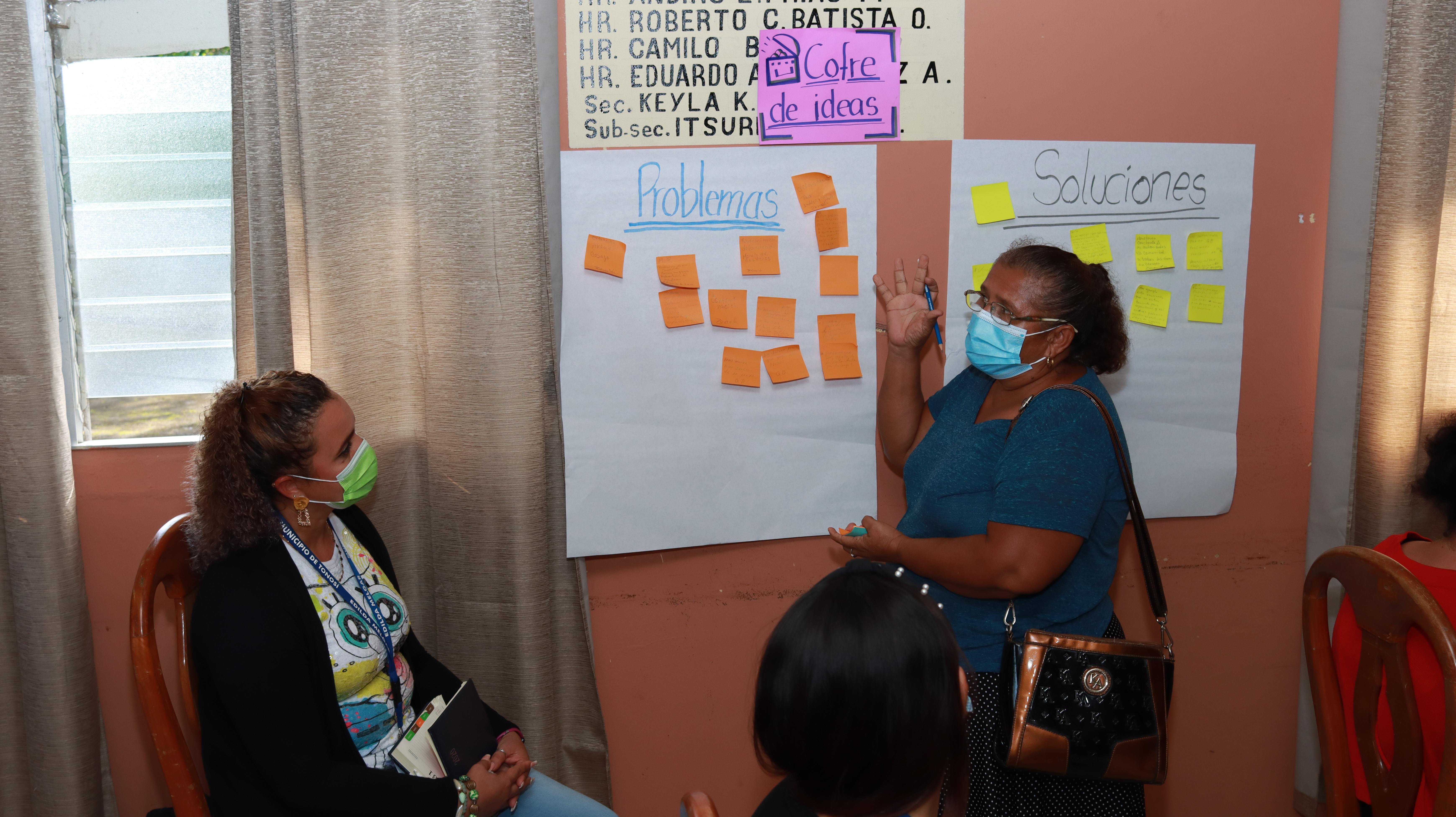

Our first learning cycle had a great start. We were invited to participate in the very first workshop organized by Azuero Sostenible to create a Network of Women Leaders from Pocrí, Pedasí and Tonosí. It was a flood of inspiration and wisdom from incredible women that have a depth of knowledge on the environmental challenges that their communities face.

We came to get our feet wet, we left with our bags and minds soaked in new knowledge, certainly, we learned that SWM is indeed a wicked problem for Azuero.

Figure 1 - First meeting of the Women Leaders Network in Tonosí, Azuero

We plan, the gods laugh.

Our plan was to go back in January and inquire deeper into Azuero’s SWM system dynamics in the field; we were ready to move forward. Then suddenly, before we knew it, we got hit by the manifestation of another wicked problem: the coronavirus pandemic. Throughout January, the Panamanian government re-established total lockdown measures due to a resurge of COVID-19 cases across the country. We had to shift our plans. As the popular proverb goes, “If life gives you lemons, you make lemonade.” We did just that.

Embracing virtuality and uncertainty.

Not knowing when lockdown measures would end, we decided to embrace uncertainty and continue our learning process remotely. Therefore, in February, we embarked a virtual journey together with the School of Anthropology and the Center for Anthropological Research at the University of Panama, Azuero Sostenible, and the Women Leaders Network.

All in all, we conducted 27 in depth interviews with key actors from government, civil society organizations (CSOs), non-governmental organizations (NGOs), businesses and academia. WhatsApp became one of our closest allies, as did voice notes and the more traditional cellphone, to ask the question: What does SWM look like at the municipal level?

Zooming into Tonosí (virtually), here is what we learned:

We found that what makes Tonosí beautiful is precisely what makes solid waste tricky: with over 10,000 inhabitants in 11 communities, it is the largest municipality in the province of Los Santos, and it has an incredibly contrasting landscape. From the mangroves and beaches to the farmlands and mountains, we wondered: How does the Tonosí municipality manage waste?

Figure 2 - Panoramic view of Tonosí's town center

It is challenging, no doubt. Based on data from the Urban Trash Collection Authority (2015), Tonosí generates -in average- 11 tons of waste a day, it only has two garbage trucks for the entire municipality, and the costs of gas and maintenance of the vehicles are high. Therefore, the service is only provided in the city center, usually 2-3 times per week.

Everyone pays the same waste collection fee for the service ($2.00 monthly). In contrast, a household that generates one or two garbage bags a week pays the same fee amount as a business that can fill half a garbage truck in one stop.

Moreover, only businesses and about 20 households pay this fee in the capital and only a few households in the outskirts. There is no effective system to collect this fee outside of the city center. Therefore, people often need to travel to the municipal office to pay personally.

Figure 3 - Panoramic view of the municipal landfil of Tonosí

The municipal landfill is unfenced and open to dispose of any type of waste. From hazardous hospital waste to dead cows and horses, everything is disposed of at no cost. While it is surveilled by a municipal guard during the week, no surveillance takes place on weekends. In addition, waste is not weighted and there is no infrastructure to classify waste or protect the soil from landfill toxic liquids.

Therefore, the municipal waste management service has many limitations, it cannot cover its own costs and it is mostly subsidized with resources from the central government of Panama.

What happens where there is no waste collection system?

Communities resort to their own waste disposal methods. The most common practices outside of the capital of Tonosi? Incineration. It is so widespread that the municipality issued a decree: people can now only burn on the 15th and 30th of each month, but it still happens frequently across communities.

When we did a literature review on SWM in the Azuero region, Tonosí clearly stood out: 6 out of 10 households incinerate their trash (INEC, 2010). We wondered why. After conversing with key actors, some pointed out commonly adopted agricultural practices, such as slashing and burning, whereas others stated it is due to a “lack of culture.”

Conversely, in the highlands of Altos de Güera and La Tronosa, where there is a high incidence of incineration, there were more contrasting views. With no access to a waste collection system and located more than 50 km from the capital, incineration is the most practical way to get rid of waste.

Therefore, burning practices may be linked to sociocultural and economic factors related to agriculture and cattle farming, but seeing incineration as a solution is also manifestation of an unmet need in terms of collection services and alternative options such as composting.

Besides incineration, we encountered other nuances in this learning process.

In communities like Guánico and El Bebedero local governments pay for waste collection. But it is not a widespread practice. Others do it mostly when community cleanups are organized, or when citizens request them to. So, this made us wonder: When local representatives do not do it, who picks up waste in communities?

During the interviews, some actors referred to people that provide a “private service.” They are described as individuals from the community or neighboring communities with private vehicles that charge between $0.50 and $1.00 per trash bag or are paid by local governments for their services.

Businesses in the tourist destination of Guánico also mentioned hiring a private service to pick up waste from hotels and restaurants, where they pay around $15.00 per week. Other businesses take their own garbage straight to the municipal landfill.

An unusual suspect for most: informal waste pickers

The lesser-known members of the SWM chain? Informal waste pickers. Most actors interviewed were familiar with them, meaning, the fact that they existed, but not much else. “I do know about them - they collect iron, copper and aluminum; I think they do it because of economic needs.”

Regardless, their role was recognized by some actors as positive for the community as they do not take waste to landfills, rather to recycling companies, which are — approximately — about than 100km away from Tonosí. There were no collaborations identified between informal waste pickers, the municipality, local governments, businesses or community initiatives. There is still a lot to understand about informal waste pickers in this exploration.

Collective Action from grassroots communities

“If we do not take care of our communities, no one is going to do it for us” says Zenaida, an environmental leader. In the tourist communities of Búcaro, Guánico, and Cambutal, there are women environmental champions that are strong mobilizers of youth, local businesses, NGOs, and government institutions to organize beach cleanings, signposting for improved waste disposal, and environmental protection activities.

School teachers are also strong mobilizers; they spoke with excitement about school farms where they used community-made compost and organized separation and recycling activities. However, there are caveats. Most of these initiatives are left by the wayside when the time comes to transport materials to recycling companies. “We started separating and filled a whole room with plastic, glass and cans, but we couldn’t get anyone to come for them,” said one schoolteacher.

Outside of schools, community environmental groups and people’s backyards showcased a landscape of creativity. From hanging decorations made of plastic to washing machine garbage cans, people show resilience and agency to deal with solid waste. It should be noted that most of the people who lead these efforts are women, which makes us reflect on traditional gender roles and how unpaid care work extends to the communities they live in and the environment.

In a broader sense, networks of actors at the regional level such as ReciMetal, ProEco Azuero, CIMA Pedasí, TortuAgro and the National Movement of Waste Pickers have the capacity to connect grassroots community actors with regional and national networks to expand and strengthen bottom up, collective action efforts.

Agrochemicals: not solid waste, but a latent concern

When asking about waste, one thing mentioned by actors interviewed was their concerns about the disposal of agrochemicals in bodies of water. It was also stressed by them that agriculture is the most important activity in the region, but something needs to be done about this issue because it affects the environment and people’s health and wellbeing.

This topic has also been discussed in participation spaces such as the municipal council and Tonosí River Basin Committee, where there is strong interest in generating evidence on the levels of pollution in rivers due to the use of agrochemicals.

Insights from our journey so far:

Between field experiences and virtuality, we have built connections and gained clarity on what is happening with waste in Tonosí and Azuero. There is certainly a lot more to learn, but here are some insights from our journey so far:

- Only 22 citizens are paying for municipal waste tax; exploring the perceptions of citizens on waste and the current municipal waste management service is key to inform how it could be improved.

- The municipality has information gaps on its SWM system that need to be further explored in order to identify leverage points where the current service model could be more efficient, without incurring large investments.

- Informal waste pickers are an unusual actor that do not seem to be part of any decision-making process. Opening spaces for their voices, participation, and concerns is necessary to make SWM more just, inclusive and resilient.

- Incineration is more than a sociocultural pattern; it is also a structural challenge where the lack of compost alternatives and the economic costs to collect and/or transport waste also play a role.

- Even though there has been motivation from some schools and environmental groups to compost organic waste, interventions often provide little to no follow-up. As a result, most of these efforts have been short-lived. Finding linkages between these initiatives and local food systems may be an alternative pathway to consider.

- The use of agrochemicals was a key concern for most actors involved, generating evidence on how much pollution from this practice is affecting people and bodies of water in Tonosí remains an area of further exploration.

- Regarding separation and recycling, the cost of transport to and/or collection of this material is too expensive for both recycling companies and communities. It is necessary to further explore how a value chain can be generated from these activities.

- The power of collective action can generate transformative SWM opportunities from the bottom up. The insights presented above are parts of a system where no actor by itself can “solve” this deeply interconnected, wicked problem. It takes a collective effort; it takes our collective intelligence.

After conducting these interviews, I immersed myself in Tonosí for 3 weeks to inquire more on these systems’ dynamics, walk with community members to see issues through their eyes and minds and participate in the second Women Leaders Network workshop, but that’s another story, another blog.

Figure 4 - Post workshop photo with some members of the Women Leaders Network of Tonosí

What’s next:

Next month, the Accelerator Lab team will do a field visit to harness the power of collective intelligence together with the inspiring people that have been part of this journey, and the many more that are joining!

###

Stay tuned for updates and if you have ideas, do not hesitate to contact us at laboratorioaceleration.pa@undp.org

Lea este blog en español aquí

Locations

Locations