Snapshot of a Recycler in Tonosí

Snapshot of a Recycler in Tonosí

March 31, 2021

Who is recycling in Tonosí? This is one of the questions that the Accelerator Lab has set out to know along with the National Movement of Recyclers and the University of Panama, in support of the Azuero Sostenible MiAmbiente UNDP/GEF to improve solid waste management in southern Azuero.

In this blog, which forms part of a series of blogs regarding solid waste management in Tonosí, we tell you the story of Mario, a composite recycler that we have constructed from surveys and interviews of 4 grassroots recyclers in Tonosí to understand how they view recycling practices in this district of the Azuero Peninsula.

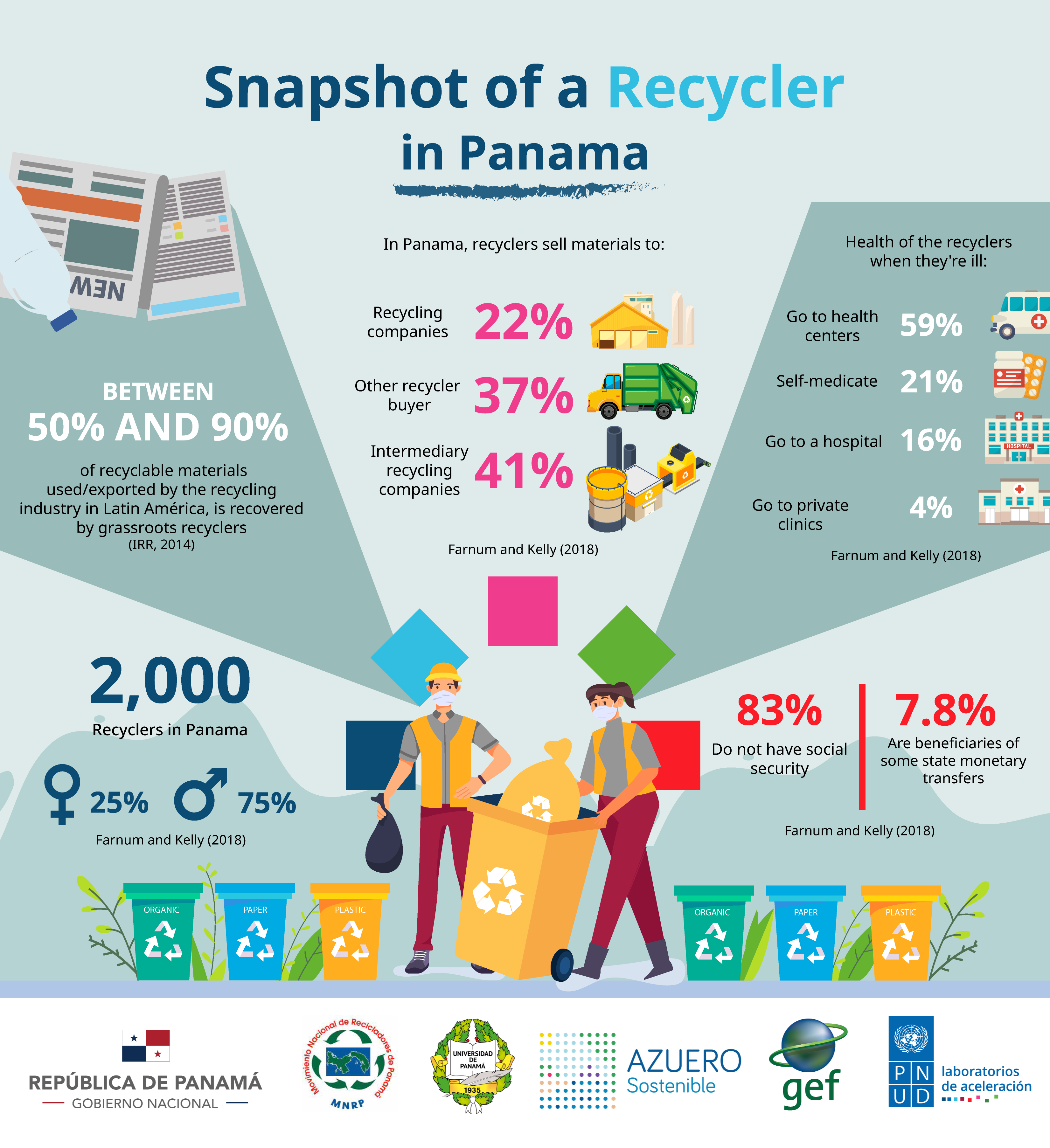

A Story of Over 2,000 in Panama

It’s 5:00 AM and Mario wakes to the crows of roosters, he makes coffee with a tortilla and gets ready to leave in his vehicle to look for recyclable materials, as he has done for the past 10 years of his life. At 63, he still feels healthy, but his body doesn’t respond like it used to, recycling requires a lot of effort.

For Mario, recycling is “cleaning up the town and the countryside,” he also benefits from the materials he can recover. That is to say, the work of recyclers addresses two perspectives of waste management: sanitation and material recovery (Ackerman, 2005). In both cases, recycling people like Mario play a fundamental role in the country’s solid waste management chain.

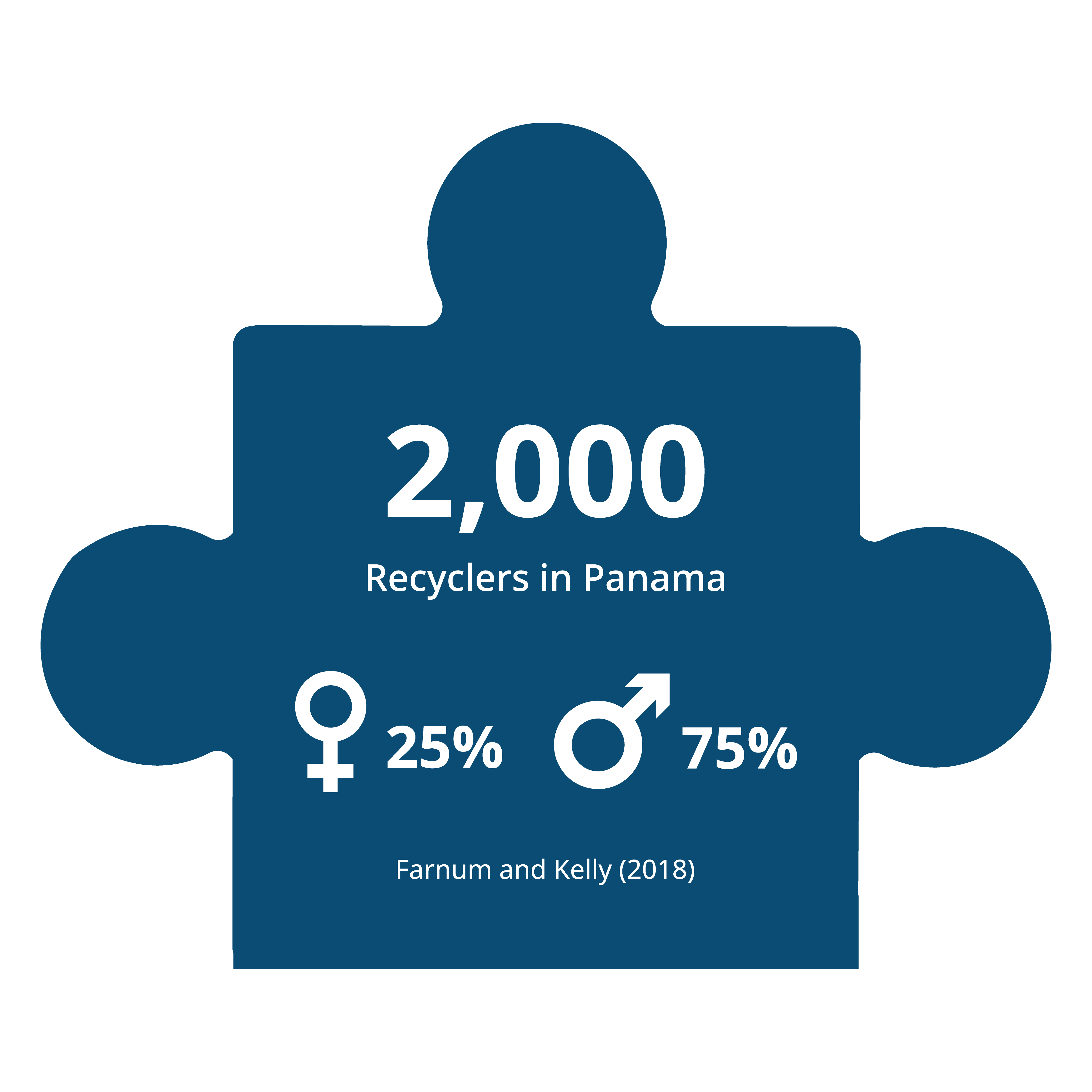

The story of Mario is one of many. According to a study by Farnum and Kelley (2018), it is estimated that there are over 2,000 recyclers in Panama, of which 25% are female and 75% are male.

Mario’s Journey is known, but little explored

Mario’s labor is not limited to material recovery from the landfill, he usually prefers to go to communities in Tonosí, because the materials he finds are cleaner and the people and businesses call him to deliver material. Sometimes they give it to him for free, sometimes he buys it. Do you want to get rid of that old stove? Call Mario and he will take care of it for you. He may not have a megaphone to announce his visits, but his name is well known in the communities, and that, in towns like Tonosí, speaks louder than the loudest horn.

Despite his broad experience in recycling, he has not been formally invited to any activity of this sort organized by the municipality and/or other organization, but he is aware of clean-up days where many recyclable materials are put out such as washing machines, refrigerators, stoves, among others. These are the good days, both in the communities and in the landfill. This is not a task to be taken lightly, because separating materials is one the principal links in the solid waste management recycling chain and his income depends on this (Farnum and Kelly, 2018).

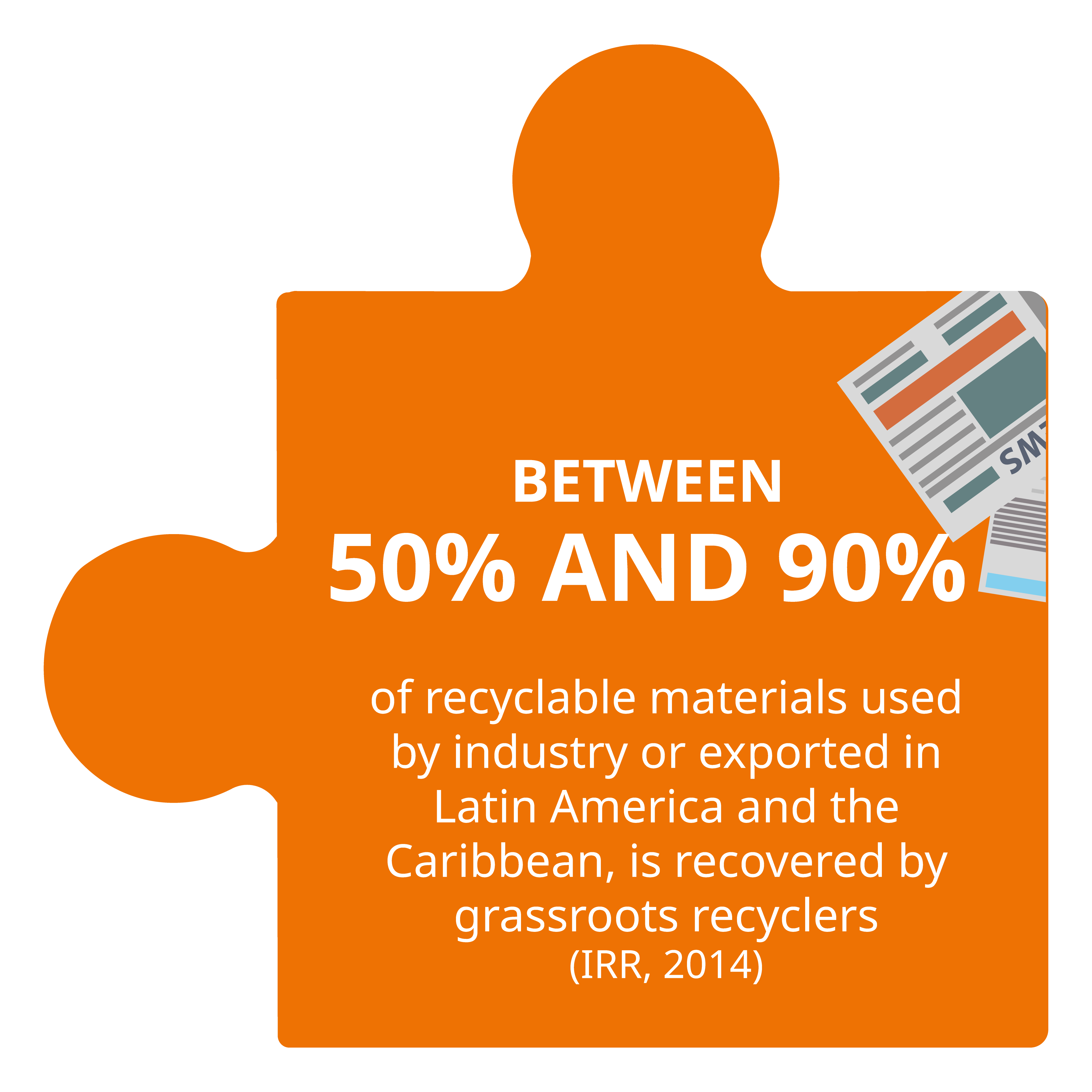

For recyclers like Mario, recovery of recycling material constitutes his principal source of income (INECO, 2017) and, at the same time, is the most effective example of material recovery in our region. The Regional Initiative for Inclusive Recycling estimates that between 50% and 90% of recyclable materials used by industry or exported in Latin America and the Caribbean, is recovered by grassroots recyclers (IRR, 2014)

However, the value orientation, attitudes and roles of recyclers have been little explored, included or recognized when it comes to developing public policies for solid waste management; despite the recent inclusion of recyclers in Article 4 of the Zero Waste Law of 2018.

According to Mario, if you don't know how to recycle, you’re a “dead man”

Mario’s life journey has filled him with a lot of knowledge and life lessons, he didn’t complete primary school, but he reads and writes proficiently to carry out his recycling activities. He recovers iron, aluminum, bronze and copper, since these bring the best prices. He doesn’t recover plastic, cardboard, or paper because there is nobody to buy it, so he dedicates his time to what works for him and generates stable income.

Therefore, he considers that he who does not know how to recycle is a “dead man,” because he has to know how to prepare the material well to sell it at a good price and also know when it’s the best time to sell it. If the prices drop very low for a long time, there may not be enough to cover food. All the recycling he recovers he stores in the courtyard of his home, at times he worries the material might be stolen, especially when he is at the landfill, so he usually remains vigilant.

Recycling: more than just separating and storing materials

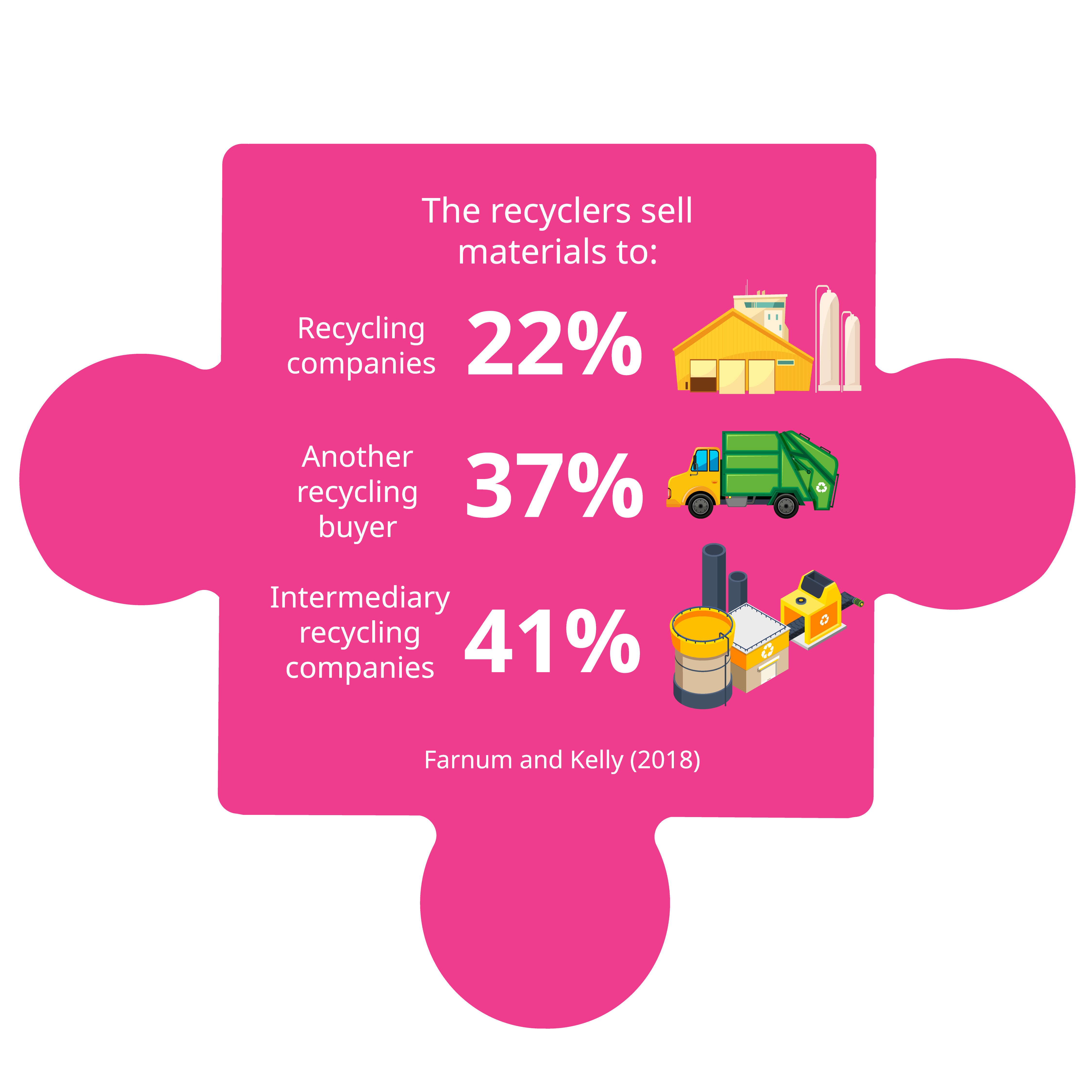

When he has enough material, Mario calls an intermediary company in Las Tablas that buys his materials, this company is the same one where the other 3 recyclers in the district sell materials. The company goes to Tonosí at least once a month, or anytime there might be sufficient material to fill a 5-ton truck, which is then sold to recycling exporters of the country.

Mario has sold to this company for the past 10 years, and he seldom sells to others, since the company has helped him economically for repairs to his vehicle on more than one occasion and Mario considers the company fair in their prices for his materials. For him, trust is worth more than selling to other companies that might pay more today, but might be gone tomorrow. The sale of recycling generates between $300.00-400.00 per month, but in summer it can be more since it’s easier to recover materials when everything is drier. Right now times are difficult, because the winter and heavy rain made recovery of materials more complicated, given that there’s more decomposition and mud both in the communities and at the landfill.

The body as your principal asset and machinery for recycling

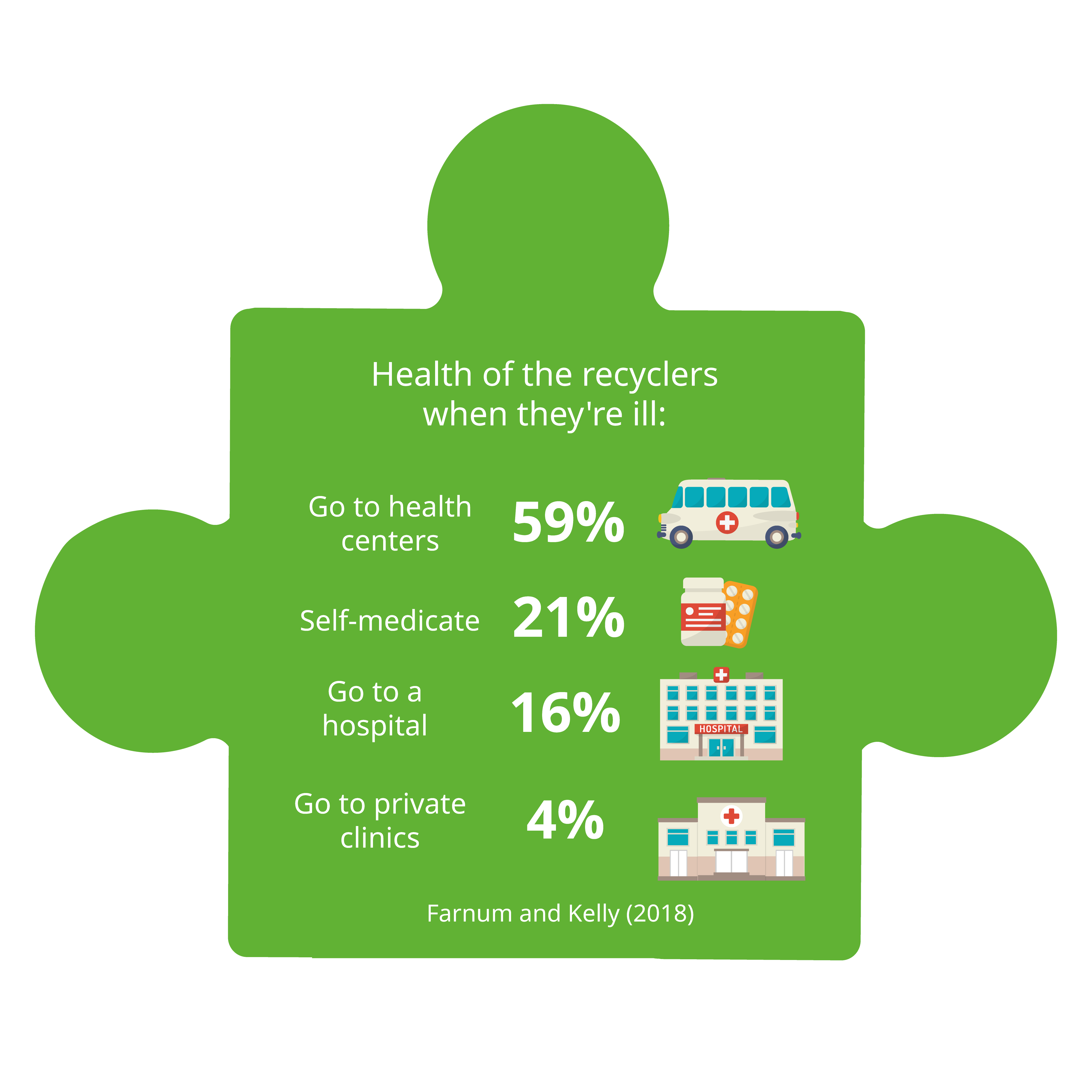

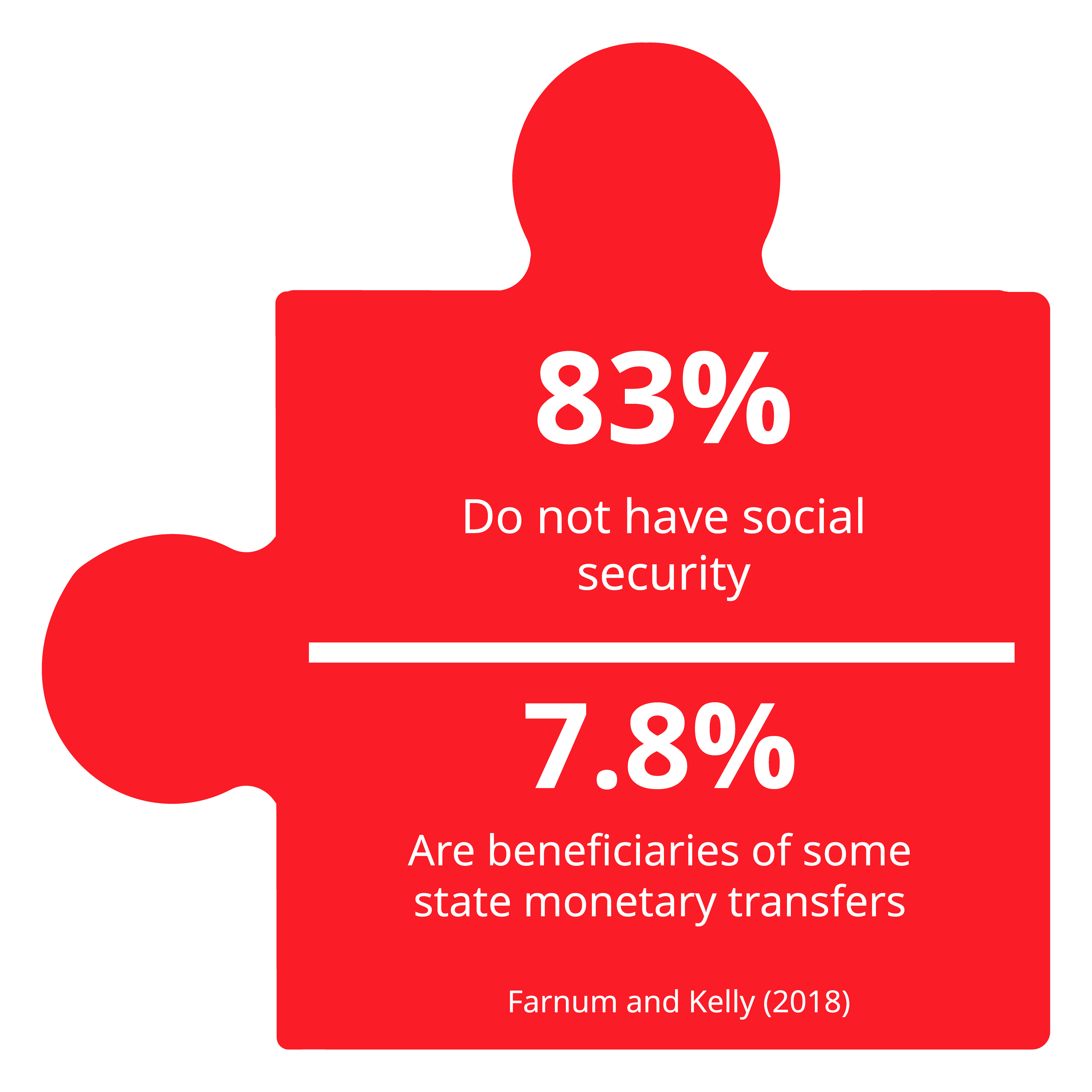

Despite his years of experience, Mario worries about recovering material in the landfill because there is a lot of smoke, mud and rotting things, but that’s how it goes to get material, sometimes he damages his gloves and only works with a face mask and boots. This has also happened while he was “whacking” material with an axe and he hurt or cut himself, in these cases he treats himself, or if it’s serious he goes to the health center in Tonosí Cabecera.

Mario always looks for options, when he’s not recycling, he is in his backyard planting yams, watermelon, cassava … caring for the chickens or doing odd jobs. Life before becoming a recycler was more agricultural, but in recycling he found a better livelihood to support himself and his dependents. Throughout his life, his body has been his principal asset since he has no social security and receives no money transfers nor other benefits from the state.

A balance between independence and collaboration

He has thought of organizing with other recyclers, but that idea is not convincing to everyone. He thinks that “everyone looks out for himself” and if some work more and others less, it will ultimately lead to conflicts. He values the independence of self-employment, at your own pace and rhythm, without a boss giving orders. Nevertheless, on various occasions he has joined with other recyclers when there is remodeling of some school or business or clean-up days where one alone can’t do enough.

Mario is always willing to learn, although now with age he asks himself how much he can absorb new things, and apart from that, time is for recycling, that is to say, his income. What he is most interested in is how to make his work easier and take less time, learning to use equipment and compacting machinery to prepare materials in better shape and sell them at a better price.

For Mario, recycling is an everyday task

Usually he returns home between 4:00 PM and 5:00 PM, but his day does not end there, at times he has to organize the material, and this can take several hours. After that, he makes dinner while listening to news on the radio. At the end of the day, Mario usually worries about covering his daily expenses, he lives day by day. For him, this is his work, it’s not that he likes it, but from this he makes his livelihood and that of those who depend on it.

Other ways of knowing and doing for the Tonosí SWM Municipal Plan

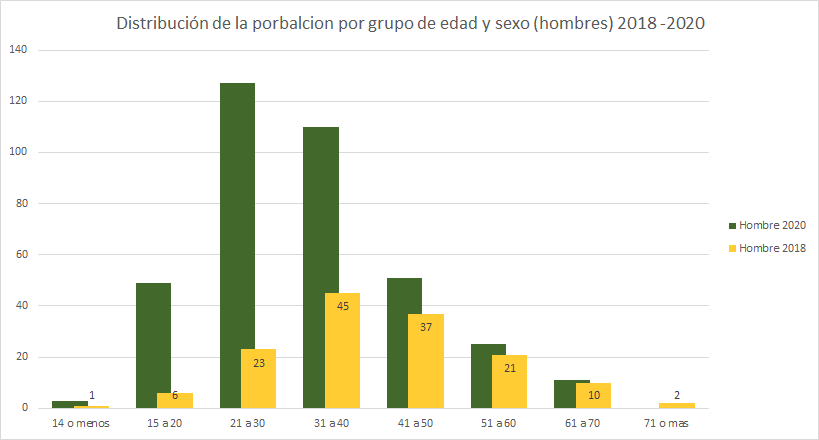

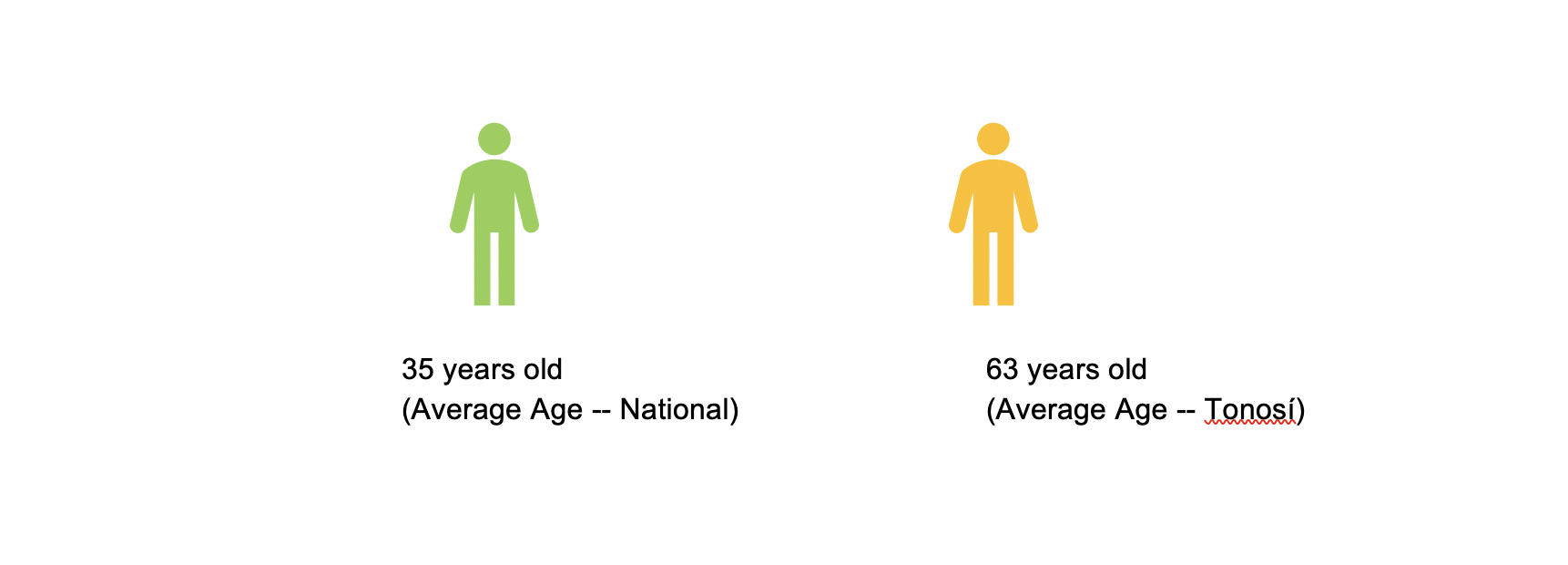

With more than 10 years of experience among the recyclers of Tonosí, their contributions to the Tonosí GRS and the country could be even more significant. Nevertheless, the conditions among the recyclers in the district, and the country cannot be ignored, they’re precarious. In the case of Tonosí, this is true not only because of the dangerous nature of recycling work and the lack of contributory or solidarity social security, but for the advanced age of recyclers, 63 on average, which deviates by more than 15 years from the average age of recyclers at the national level, which is 35 years old (Farnum and Kelly, 2018). This number does not include itinerant recyclers that travel from other districts to Tonosí.

Figure 1. Distribution of the population grouped by age and gender (men) (Farnum and Kelly, 2020)

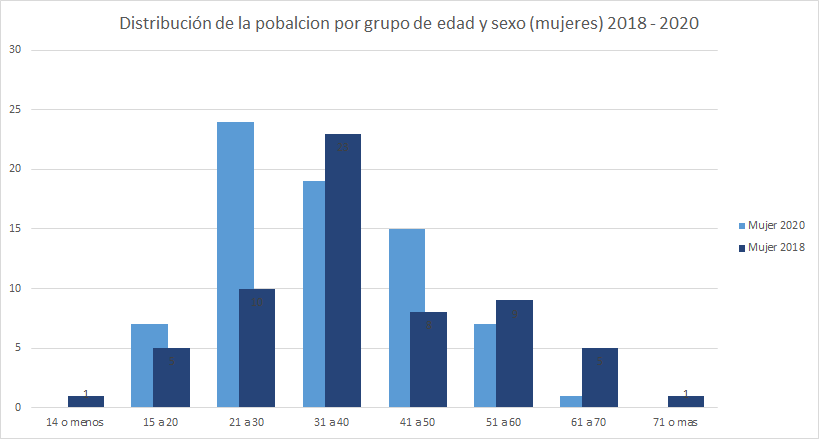

Figure 2. Distribution of population by age and gender (women) (Farnum y Kelly, 2020)

Another relevant aspect is related to the gender distribution of recyclers in Panama and Tonosí, according to the latest profile of recyclers at the national level, 25% are women and 75% are men (Farnum and Kelly, 2018). At the time of writing this blog (July 2021), we have not identified any women performing the recycling trade in Tonosí.

Nevertheless, national tendencies have shown a significant increase in women recyclers according to the updated national profile of recyclers in Panama (Farnum and Kelly, 2020). These data show a distinct trend from the findings of our sister laboratories such as in Vietnam, in which women have been identified as the principal recyclers of the country.

Therefore, recognizing the work, knowledge and practices of recyclers and including them in the design of waste management plans, contributes to the development of effective and efficient waste management models. Evidence of this was the participative workshop held in June, organized by MiAmbiente, the Sustainable Azuero initiative and UNDP in a session of the Municipal Council. The workshop had as its objective defining the challenge of solid waste with government institutions, community leaders, NGOs, businesses and a representative of the recyclers of Tonosí. In this space, the voices of recyclers were recognized and heard through the representation of a grassroots recycler who described their knowledge and practices to the participants, generating some of the most relevant contributions to make recycling effective in the municipality.

Collective action to strengthen the recycling value chain

Nevertheless, there are also the collective processes of the recyclers, whereby the National Movement of Recyclers has played a key role in the defense and promotion of the rights of grassroots recyclers in Panama and the Latin American region. This work is key to a situation in which landfill closures are planned at the national level and the growing efforts toward a transition to a circular economy, through Law 187 which prohibits single use plastics, the Zero Waste Law and its guiding principles, such as responsibility extented to the producer/manufacturer.

Figure 1 – workshop on human rights for recyclers, by the National Movement of Recyclers of Panama

Therefore, beyond timely participation in workshops activities related to GRS, it’s necessary to recognize the rights and work of recyclers; as well as their inclusion in strengthening the value chain of recyclable materials along with other relevant stakeholders in the GRS. About this, there are 3 key points to consider:

(i) Access to material, because recycling is the livelihood of recyclers

(ii) Recognition and inclusion of their rights, knowledge, and practices for more effective recycling and,

(iii) Payment for services performed by recyclers for recycling services

Sister Labs such as in Paraguay and Vietnam have generated interesting learnings that highlight the importance of recognizing and incorporating the knowledge and practices of recyclers, and at the same time, strengthen the relationship of trust between citizens, institutions and businesses to do recycling more effectively through collective action.

In the particular case of recyclers, this articulation would be of great benefit, as it could increase the quantity and quality of recovered materials, with better working conditions, which will contribute to increases in their income and improve their living conditions. In addition to the environmental benefits generated by this work for the country.

Do you want to know more about what we are working on to strengthen the recycling value chain in Panama? Stay tuned to learn more about it in our next blog!

We have done this snapshot in partnership with the National Movement of Recyclers (MNRP, its Spanish acronym) and the University of Panama, applying the tools developed by Farnum and Kelly (2018) together with MNRP for the first profile of recyclers in Panama. This study included the National Movement of Recyclers from the design of tools until the presentation of the final results, an outstanding and unique example for the Latin American region, you can see the complete publication here.

###

Stay tuned for updates and if you have ideas, do not hesitate to contact us at laboratorioaceleration.pa@undp.org

Lea este blog en español aquí

Locations

Locations