The San Felipe Neri Public Market, its transformations – and its future.

March 13, 2023

The San Felipe Neri Public Market —el Neri— is full of anecdotes and experiences that tell us about changes in time and provide lessons for Panama City’s new public markets.

“Scientists say we are made of atoms, but a little bird told me that we are made of stories”, Uruguayan storyteller Eduardo Galeano once said.

In the case of el Neri, this is absolutely true. Thinking about the public markets of the future, vendors and public officials at el Neri are overwhelmed by an endless stream of stories about the significance of their market in the very heart of Panama City.

The San Felipe Neri Public Market on Panama City’s Old Embankment

Many of us born in Panama City have heard older relatives reminisce about what el Neri once was, how the Calle 12 buses left you just a block away, how it offered everything you needed to put a meal on the table. A vendor from el Neri, who still lives in its surrounding Santa Ana barrio, was nostalgic as she shared how on Sundays the people of the San Felipe, Santa Ana and El Chorrillo barrios walked down to purchase at el Neri: “It was as if the market walked towards you.”

The San Felipe Neri Public Market in 2016.

However, over time el Neri began to deteriorate, to the point that it became a hazard for its visitors, clients, and vendors.

In 2017 the Municipality of Panama began to renovate el Neri and by the end of 2020 the new San Felipe Neri Public Market opened its doors to the public —no longer at Panama City’s old embankment, but on Avenida B across the entrance to Panama City’s Barrio Chino.

Although the old Neri still lives on in the memory of the public officials, vendors and customers who knew it, “The market that once was, no longer exists”, as one vendor put it. “But that’s not necessarily bad”, added another seller. In the midst of such daily discussions about el Neri’s transformations, its vendors’ reflections invite us to think: at the heart of so many memories, what can we learn about the future?

The new San Felipe Neri Public Market.

The stories of el Neri’s sellers are diverse. During a workshop with us, twelve market vendors shared their thoughts about life in el Neri, as well as their daily routines, concerns, and aspirations, in order to collaboratively design solutions that take into account their realities and contexts —and they shared important lessons to map out “future-proof” public markets.

The new San Felipe Neri Public Market.

Three learnings

“Many of us used to live right here in Santa Ana,” a saleswoman told us. “Now we live outside [Panama City’s] downtown, but we have always sold here.” Furthermore, “of the people who buy here, almost none are from Santa Ana. The barrio has changed and many of the people who used to live here are gone, they have left”, she concluded.

Map showing the distances our workshop participants must commute to reach the San Felipe Neri Public Market.

A first lesson is that public markets do not exist in a vacuum; their relationship with the historical, social, cultural, and economic dynamics of the territories where they are located implies that these dynamics must be recognized and incorporated as part of their identity for public markets to remain relevant over time.

Workshop with twelve San Felipe Neri Public Market vendors.

However, beyond el Neri and its vicinity, there are also the particular realities that its vendors face daily. When sellers shared a day in their life with fellow workshop participants, the story of Deyanira Sánchez, who works at the Fonda Delineth eatery, deeply resonated with her peers.

For Deyanira, working at el Neri is no easy task. Her family members have dedicated their whole lives to selling in the market and this is something she does with love because it’s part of her family tradition:

“My day starts at 2:00 AM, when I thank God for one more day of life and for my children. After getting myself ready and leaving everything set up at home, I leave my house at 3:00 AM to first prepare and then serve breakfast at el Neri until 8:00 AM. Then there’s almost no time to rest; after selling breakfasts, I must start preparing lunch at 9:00 AM; it’s at that time that I eat breakfast myself.

“From 11:00 AM to 2:00 PM I serve lunch, then I clean the fonda [small affordable restaurant] and go to the bus terminal to grab a bus home to Arraiján [a small town 30 minutes from el Neri by car]. I get home at around 5:00 PM to talk to my children about their day and prepare dinner for them. Before going to bed, I thank God for all that He has given me that day and I rest between 7:00 PM and 2:00 AM the next morning —and that’s how my day goes.”

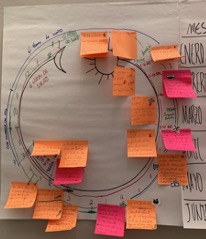

Participants built an hour-by-hour model of their routines, exchanging experiences and highlighting their main concerns and aspirations in relation to their lives in el Neri. Source: UNDP Panama.

Like other participants, another vendor called Zulay mentioned that her main concern is the drop in market sales and her safety when commuting at such early hours. Her main aspiration is to be able to support her family, see her family members grow and spend more time with them.

A second learning is that the people who sell at el Neri —and their stories— are key to design solutions. It is therefore necessary to understand, empathize with and build solutions that work for vendors’ realities and contexts. We cannot talk about a circular economy without placing people at its center.

According to the vendors we interviewed, people from el Neri’s neighboring residential buildings, like the one pictured here, hardly ever visit it.

A third learning is that a public market is only as relevant as the communities it serves.

“The customers whose money I depend on are tourists and buyers from restaurants or elsewhere,” says one saleswoman. “Almost no one [purchasing at el Neri] comes from here.”

One of the most relevant learnings emerging from this common space for reflection with the vendors from el Neri is that their main clientele are not from this market’s surrounding barrios, but from other parts of Panama City.

Is el Neri ready to welcome the future?

El Neri has changed —and so have its surroundings. During our discussions with its vendors, questions arose about how el Neri can continue to be an active part of the memory of its barrio, Santa Ana, and its people. Those who were, those today, those who shall come next.

If a public market is embedded in an evolving context, how does it remain relevant to that context over time? And if it does not renew its relevance, what is its purpose in the future?

Our curiosity was piqued as we shared more about these reflections, leading us to explore ideas in conjunction with the people of Santa Ana, which in turn led us to a community mapping phase to understand the factors that facilitate or limit access to el Neri for its surrounding communities. This shall be the story of our next blog.

This blog is part of a series on learning activities and reflections generated by the UNDP Accelerator Labs, together with the Public Markets Bureau of the Municipality of Panama and the Panamanian non-profit Re-inventa, within the context of developing the Integrated Municipal Public Markets Network (RIMMU for its Spanish acronym). To learn more about our methodology and process, please feel free to read our full publication here.

Locations

Locations