Theme 1

When democracies

autocratise

In a world of compounding shocks, governing in a state of emergency is becoming the new normal. There is a danger that policies formed in a constant “state of exception” will erode democracy further, at a time when even longstanding democracies are under pressure.

Signals

Threats to democracy are growing, as global freedom declines [4] for the 16th consecutive year. Between 2016 and 2021, the number of countries moving towards authoritarianism was more than double [5] the number moving towards democracy. Satisfaction with democracy has fallen [6] in most parts of the world. Some 52% of people across 77 countries agreed that having a strong leader [7] unbeholden to legislatures or elections is a good thing (compared to 38% in 2009).

The nature of autocratisation is changing, too. [8] 2021 saw six coups, a sharp break from an average 1.2 coups per year since 2000. Polarization is increasing to toxic levels, as respect for legitimate opposition and pluralism declines, while autocratic leaders are increasingly using misinformation, repression of civil society and media censorship to empower their agendas. Covid was widely used to justify restricting civic space [9] . At least 31 countries used military ordinances [10] or force to enforce pandemic restrictions.

Progress made towards gender equality, interacting with autocratization and polarization, has prompted a gender backlash [11] in several countries.

There are diverse motivations and methods [12] behind democratic backsliding. The personalization of politics has been reinforced by social media and a more digitalized world where everyone has a voice, no matter how ill-intentioned or informed. Where democracy was already under pressure or institutions are weak, shocks can serve as an accelerant. A new study of the effects of extreme weather on small island nations concluded that natural disasters could fuel autocracy[13], as constant shocks overwhelm countries' ability to respond[14].

There are also signs of democracies being tested, but proving resilient. The response to the 2021 attack on the US Capitol, for example, showed that institutions of democracy can and do function to preserve democratic freedoms. Brazil’s elections chief [15] was granted unilateral power to order removal of online misinformation ahead of national elections (though prompting concerns that this was itself a potentially dangerous expansion of power). Chile responded to demands for a more inclusive democracy through an elected Constitutional Assembly [16], although its new proposed constitution was rejected by voters.

Trends

- Democratic backsliding

- Increasing polarization

- Climate shocks - more intense, more frequent

Illustrative Signals

Covid widely used to justify restricting civic space

Autocratic leaders increasingly using misinformation, repression of civil society and media censorship

New study shows natural disasters could fuel autocracy

Contested elections (eg US, Brazil)

So what for development

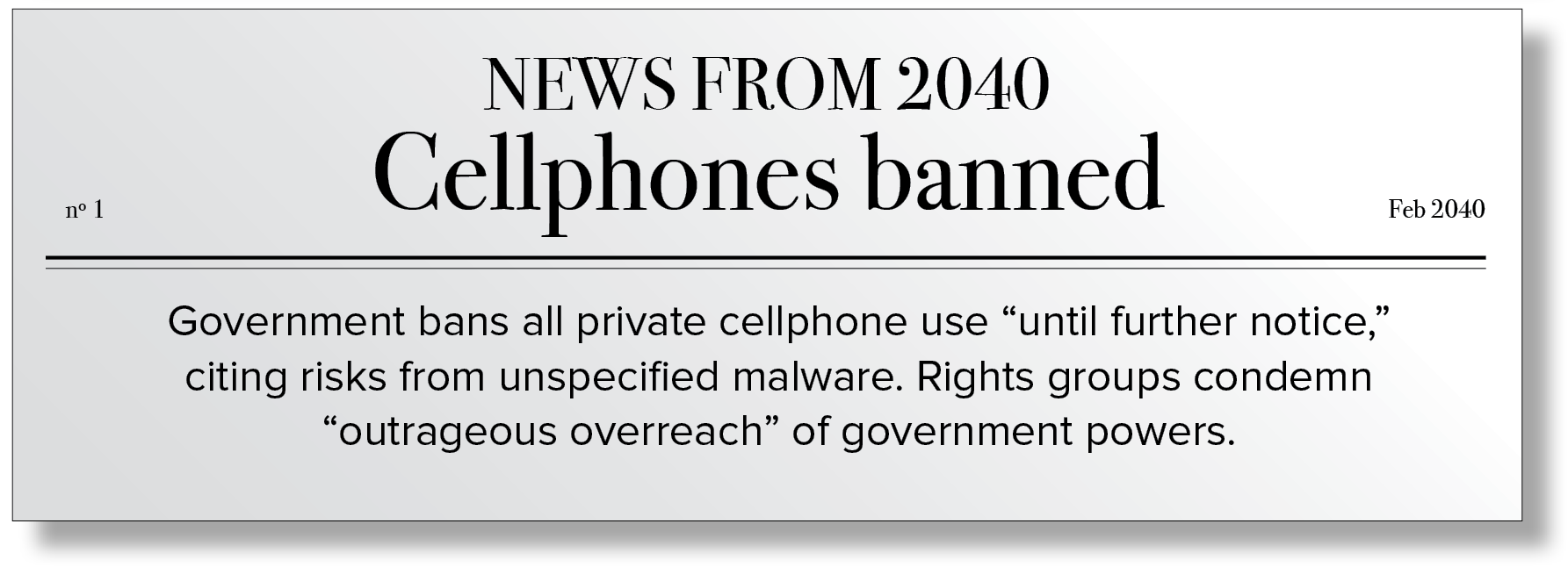

Crisis management requires “command and control”. Some 9 out of 10 constitutions worldwide in force today include emergency clauses [17] that allow the government to step outside the ordinary constitutional framework to take emergency action (and some countries have adopted brand new legislation granting governments new powers to respond to COVID-19).

Such measures can, and sometimes do, lead to abuse of power and the deterioration of democratic principles in the long term. How do we balance the need to govern effectively in crisis with the preservation of democratic principles? In an age of crisis and shocks (unforeseen by constitutions centuries old), finding this balance – agile and adaptable government that is still effective, accountable and inclusive - demands new ways of governing. For example: decentralized autonomous organizations, which can give everyone in a community equal rights, recording decisions in a transparent, immutable manner on the blockchain, depending how they are set up. [18]

Regardless of what these alternative governance systems look like, to be trusted and effective they need to be grounded in inclusive and equitable social contracts that reflect the needs of our and future generations.

Yet as autocrats minimize women’s equal rights [19] and their participation in the workforce and politics, women are left underrepresented and their choices constrained, a profoundly undemocratic outcome. The gender backlash includes pushback on reproductive rights, gender-sensitive education and ending gender-based violence, further threatening women’s rights and opportunities.

The uncertainty of today’s world is increasing human insecurity, fueling polarization [20] , distrust and embrace of extreme views. That in turn makes it even harder for people to come together around difficult choices for sustain- able change, creating a vicious circle as people are further entrenched in their own like-minded groups.

Imagining the future

What might our world look like in 2040?

Fictional snippets from a possible future!

Locations

Locations