An integrated approach is key to ending malaria and unlocking sustainable development

Poverty and malaria are linked. Can we tackle them together?

April 24, 2024

Azerbaijan and Tajikistan were certified malaria-free in 2023, with their success supported by water management on cotton and rice plantations.

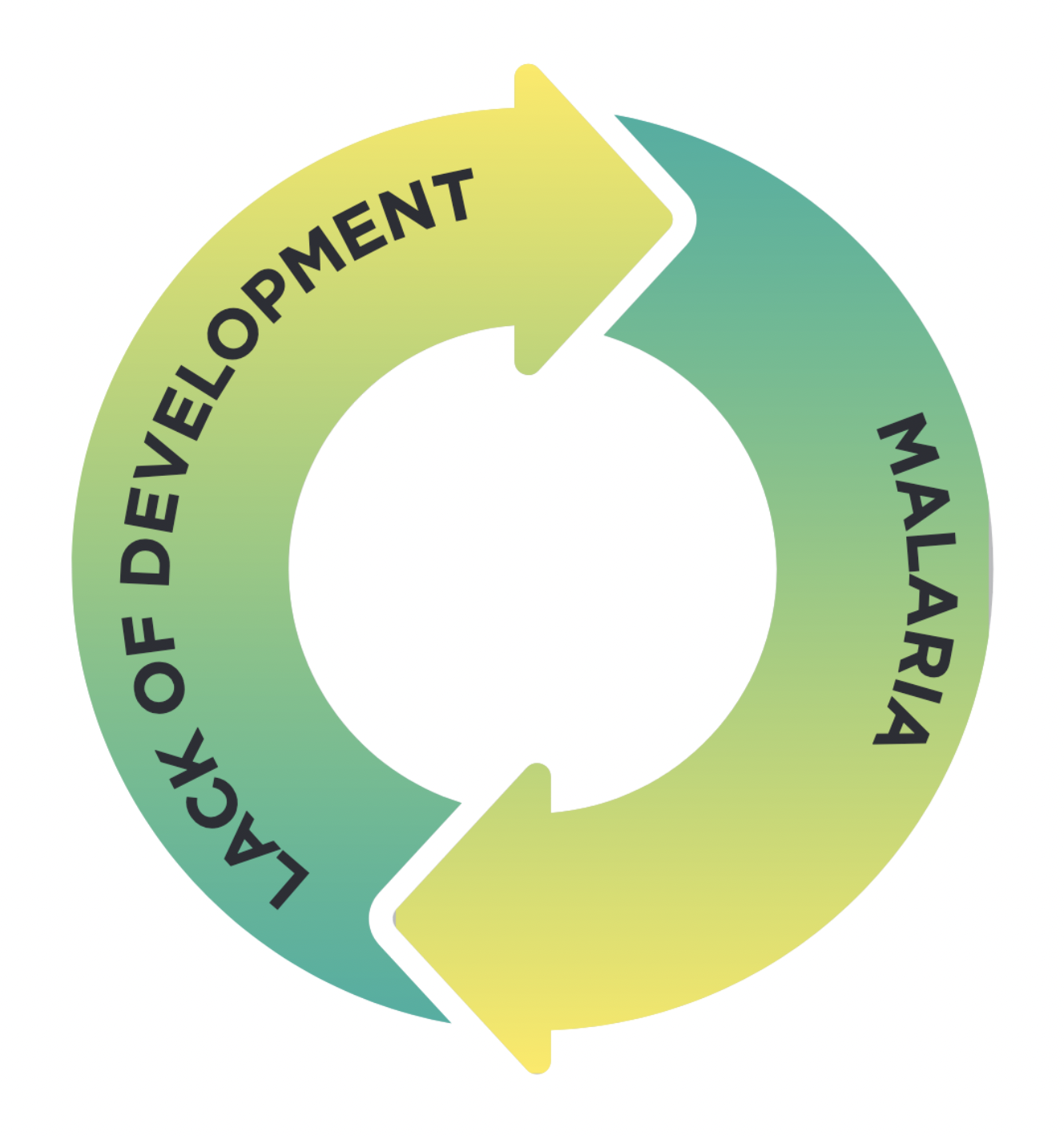

Malaria is highly correlated with poverty and development. While two new vaccines promise to strengthen malaria responses, progress in reducing cases has stalled for two decades. Business as usual approaches will keep countries from ending malaria and advancing human development.

In 2020, almost half of households in low- and middle-income countries spent more than 40 percent of their income on healthcare, threatening to push 1.9 billion people in areas with malaria into poverty. Limited data since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic suggest worsening conditions for healthcare spending and foregone care worldwide.

Malaria claimed more than 1,600 lives a day in 2022—mostly children under five years—and accounts for half of preventable school absences in Africa, robbing communities of their full potential. In countries with high transmission, health systems are overwhelmed with cases, depleting limited resources for essential services.

But malaria is also influenced by factors such as economic inequities and environmental conditions. It primarily affects people with less education and lower incomes, who live in unprotected homes and work in agriculture, which exposes them to mosquitoes that transmit malaria.

Simultaneously, climate change, conflict and displacement, such as the return of 1.3 million Afghans from Pakistan, threaten to “supercharge” and reverse progress against malaria, with climate change putting an estimated 3.6 billion additional people at risk of malaria by 2071.

Changes in poverty and population distribution, natural environments and housing can change disease dynamics. So while traditional malaria interventions remain essential, concerted actions beyond the health sector are needed to meet our commitments to end malaria by 2030.

Several countries demonstrate this.

Malaria cases in Sri Lanka increased historically as irrigation and agricultural projects exposed people to infection. By the 1990s, improving living conditions and concurrent declines in other diseases, in addition to successful anti-malaria programmes, suggest that development overall helped Sri Lanka eliminate malaria in 2016.

Azerbaijan and Tajikistan were certified malaria-free in 2023, with their success supported by sustainable development efforts such as water management on cotton and rice plantations, mosquito larva-eating fish and health outreach for agricultural workers.

UNDP, UN-Habitat and the RBM Partnership to End Malaria developed the Comprehensive Multisectoral Action Framework: Malaria and Sustainable Development to guide integrated approaches that unlock mutual benefits across disease and development dimensions.

Pathfinder endeavour

Implementing this framework starts with identifying the districts with the most unrelenting malaria, which strongly correlates with the most vulnerable people experiencing persistent development challenges. Local government and partners from sectors that influence malaria must also be committed.

These sectors are grouped into five dimensions of the Sustainable Development Goals; health, political and institutional, social, economic and environmental. Targeted actions across all five groups could address both the root causes of malaria and the lack of development leaving people furthest behind.

Partners further commit to “malaria-smart” engagement with local businesses, employers and human activities that produce and reduce malaria, while minimizing inequities within the district. Finally, robust data analysis, citizen engagement and local council oversight continuously reinforce accountability for programme objectives.

Pathfinding in action

Uganda, which had the third highest number of malaria cases globally in 2022, is among the first countries to test this strategy. It could provide lessons for employing existing programmes and resources to further realize health and development benefits in other countries.

Five districts with especially vulnerable populations, including refugees, sex workers and people in informal settlements, and opportunities for integrated approaches through local champions have been identified.

UNDP and our partners are now developing an impact and investment case study to understand the local dynamics between malaria and development, the benefits for communities, districts and businesses and the costs of action and inaction. The study is the next step to building support for integrated approaches across public and private sector actors, both at the district level and nationally.

Beyond business as usual

Renewed ambition and accelerated action are essential if we are to achieve the 2030 Agenda and a malaria-free world. If current trends persist, we will likely miss global targets for malaria reduction, requiring bold changes to get back on track.

Funding continues to fall dramatically short of the US$7.8 billion needed annually to reduce malaria cases and deaths by 90 percent by 2030. Climate action and better tools and data for local delivery, including integrated multisectoral approaches, are key to ending malaria and unlocking wider development gains.

As we mark World Malaria Day, whose 2024 theme is “Accelerating the fight against malaria for a more equitable world,” we must move beyond business as usual and find synergies across sectors that address the drivers of malaria and advance human development for everyone.

Locations

Locations